JTF (just the facts): Published in 2015 by Rorhof Books (here). Hardcover, 414 pages, with more than 2000 color reproductions/thumbnails. Includes an essay (in English, German, and Italian) by Joachim Schmid. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: While Google Street View has gotten all the fanfare as the preferred public video source for artistic mining, the lowly net-connected webcam (multiplied by likely tens of thousands) shuffles on in the overlooked background, continuously staring out at airports and weather stations, ski hills and traffic intersections, endlessly spooling up minute-by-minute footage of the mundane. While at first glance, such imagery wouldn’t appear to be a likely candidate for serendipity (most of these cameras are looking out at fixed locations, doing everyday jobs), the fact is the world is surprisingly full of accidents, coincidences, and wonders, and these cameras are inadvertently there to record them. So in an unlikely variant on the tortoise and hare story, webcam archives are turning out to be a more powerful resource than we might ever have imagined.

For the past 15 years, Kurt Caviezel has been monitoring some 15000 individual webcams all over the world, intermittently taking screenshots of his finds. (As an aside, in a meaningful feat of typographical miniaturization, every webcam address he’s been monitoring has been listed on the cover of this book in astonishingly small type.) His image archive now numbers over 3 million photographs, and if we assume that he had little or no use for 99+% of what passed through the lens of any one camera, what he’s built over time is a catalog of outliers – those fleeting moments when something unexpected happened that was worth capturing.

From there, Caviezel has imposed order on the chaos, randomness, and chance, grouping the images into subject matter categories and organizing them into typologies. Shown in alphabetical order by title, they are an encyclopedia of found oddities, a thick table of visual patterns that have emerged out of the torrential photographic noise. Not surprisingly, many of his groupings gather up observations of places and things: dams, lighthouses, observatories, windsocks, and the like; it seems that regardless of our specific place in the world, we have an innate need to endlessly watch bus stops, zoos, and swimming pools.

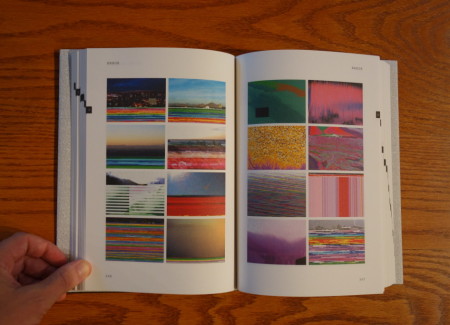

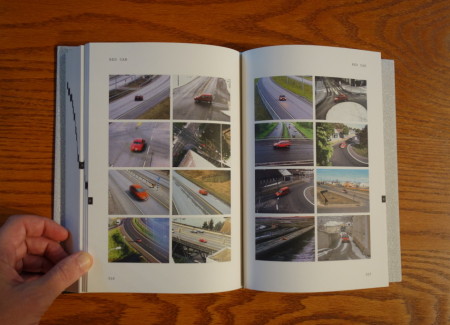

Of course, things get more interesting when something unexpected happens, and Caviezel is right there to prove to us that the unexpected is never actually that unusual – that exciting once-in-a-lifetime ephemeral moment has happened before somewhere else, and it’s there to be found in the archive. The moment when the sun turned black, or the single lonely cloud passed overhead, or lightning struck, or the sky turned into a painting by Caspar David Friedrich, they’re all actually repeated events, seen in Caviezel’s book as taxonomies of extremes. These unlikely repetitions pile up: the single red car, the passing FedEx truck, the chemtrail in the sky, the drifting paraglider, the ubiquitous plastic chair. With thousands of simultaneous feeds looking out on the world, it’s no wonder that some synchronicity occurs, but as seen in this rigorous format, the parallels are everywhere.

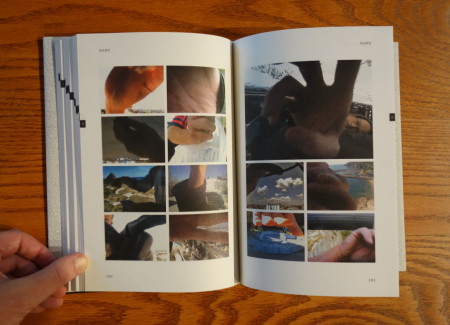

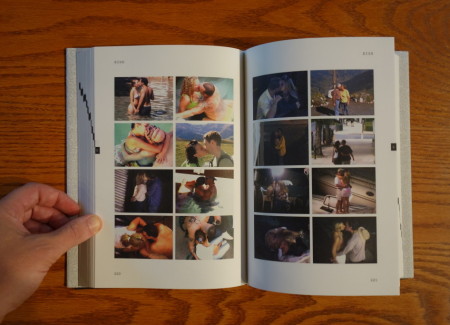

When humans enter the frame, our behavior is remarkably routinized as well. Caviezel captures both voyeuristic views of bathers, weddings, photographers at work, and surreptitious kisses, and overt displays aimed at the camera – the friendly wave, the thumbs up Yes!, the bike raised in triumph, and the bare ass shown in playful defiance of authority.

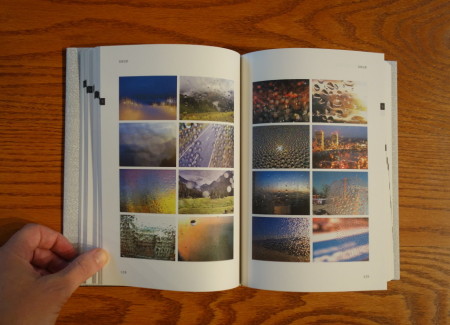

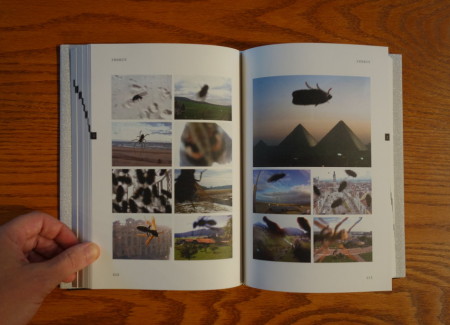

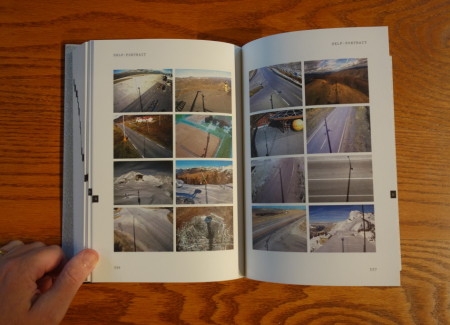

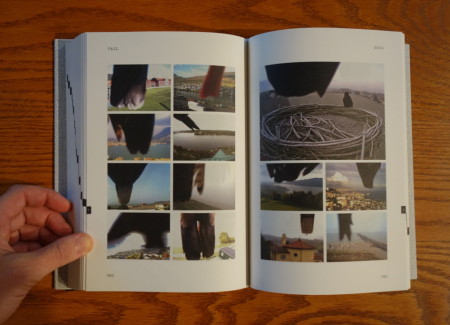

Many of the best images and visual themes are found among the categories devoted to the webcam infrastructure itself and the multitudes of problems and interruptions that can occur. The lens is routinely obscured – by snow and ice, dirt and dewdrops, fog and spiderwebs, all with unlikely beauty. Insect and birds land on the camera, walk across the lens, and let their tails hang down, as if commenting on the view behind them. Window frames, cable clutter, and scaffolding surround the camera, and worker’s hands reach up to make adjustments, and when it all goes to hell, a rainbow parade of multi-lingual error messages and fuzzy static takes over. There are even webcam selfies, where the mounted camera casts a shadow down into viewing area, in effect taking its own self portrait. Seen in groups and clusters, these commonalities are quietly endearing, a kind of wry deconstruction of the medium itself.

I imagine Caviezel’s process must be something akin to panning for gold or searching for buried treasure on a sandy beach – the hit rate for something valuable must be extremely low. This makes his encyclopedia that much more intriguing; it’s brimming with exceptions, outtakes, mistakes, and outliers, seen with an eye for humor and eccentricity and organized for clever efficiency. That these images then coalesce into definable patterns is even more surprising, or maybe not so, given the statistical laws of large numbers. In the end, it’s this back and forth thinking process about the nature of pictures (however sourced, intentional or not, original or not) that is the takeaway from Caviezel’s photobook. There’s an undeniable flood of imagery out there ready to drown us, but with the application of the right filter, suddenly that deluge is full of insights and delights.

Collector’s POV: Kurt Caviezel does not appear to have gallery representation at this time. Interested collectors should likely follow up directly with the artist via his website (linked in the sidebar).