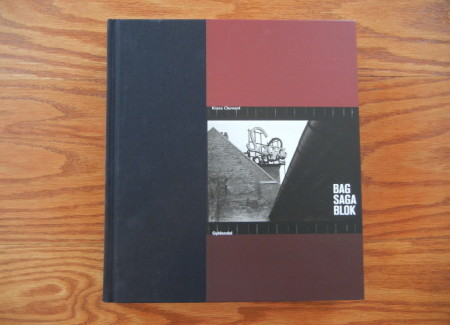

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2014 by Gyldendal (here). Hardcover, 224 pages, with 191 black and white and 8 color photographs. The images were taken between 1963 and 2010. There are no texts or essays included. (Spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Long term neighborhood stories are inevitably about transformations, some that are blatantly obvious and others that are so slow and incremental that they are nearly imperceptible. People move in, people move out, old becomes new, new becomes old, and the remnants of the past and the clues to the future comingle in the swirl of everyday life. Photographs help us chart these ebbs and flows, documenting the extremes of good times and bad, and the subsequent cycles of decline and rebirth.

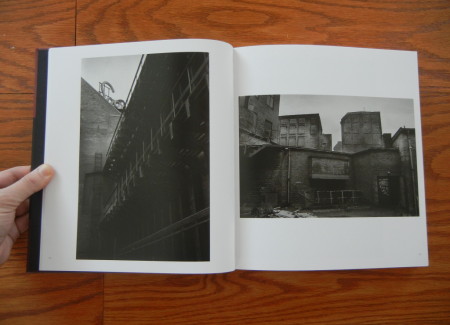

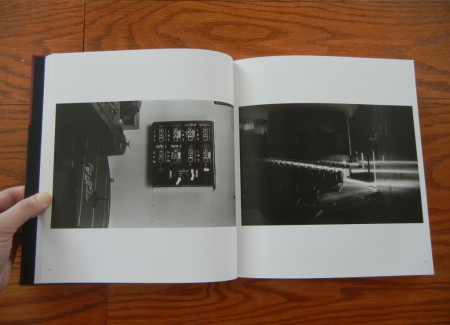

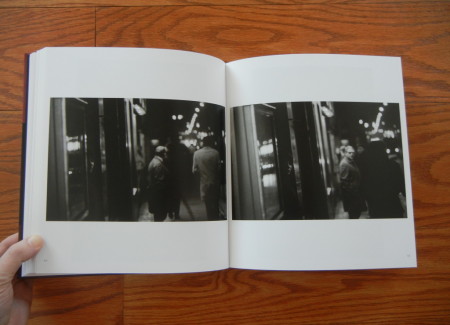

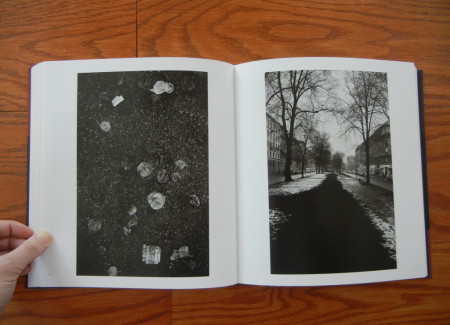

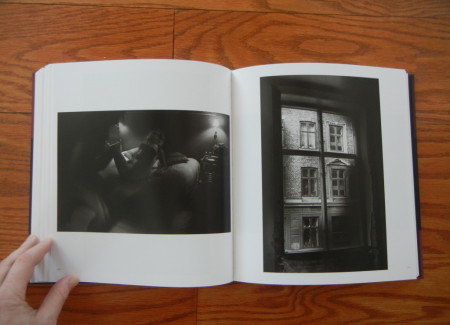

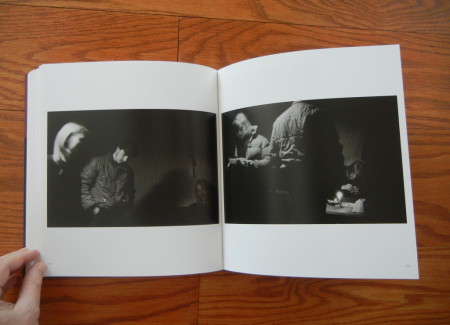

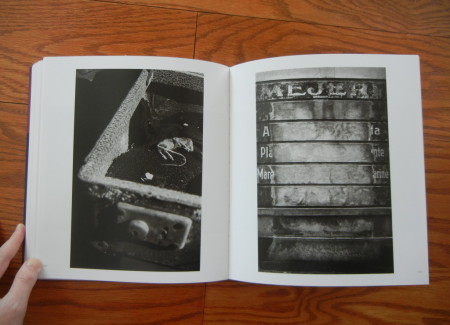

Krass Clement’s fifty year portrait of the streets surrounding an old movie theater in Vesterbro, Copenhagen, follows the neighborhood’s up and down undulations using an impressive breadth of photographic styles, each thoughtfully applied at just the right moment to match a particular visual need. Clement sets the stage with crisp architectural studies of the back of the building, where planes of brickwork, rhythmic wooden planking, metal hand rails, and the aging neon sign are seen from multiple angles, jumping from one vantage point to another with angular precision. After a quick interlude inside (to see the rows of empty seats and the obsolete projection equipment), he takes us out into the daytime streets, where folks go about their daily business, storefront windows offer shoes, and apartment blocks (more brick patterns) loom above. It’s clear from the mix of locals that this neighborhood is in the midst of a slow downward tumble – the combination of the elderly and the young passersby says that the rents are cheap. As we wander along, Clement’s street photographs opt less for the clever juxtaposition of unexpected moments and instead trend toward the moodily atmospheric. As night falls, he peers through tram cars, turning wet streets into dark blurred impressions. Amid the shadows of the streetlights, he brings in a more cinematic multi-frame sensibility, using paired images to capture the time-elapsed action of creeping out from a doorway or turning to look back at someone passing by.

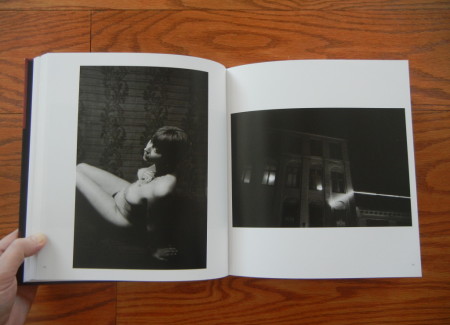

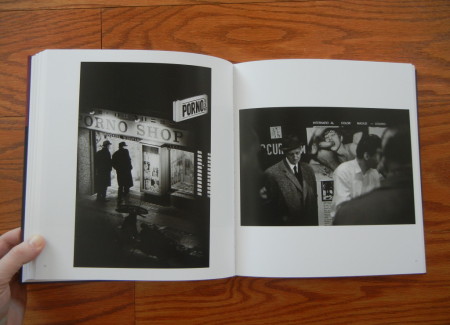

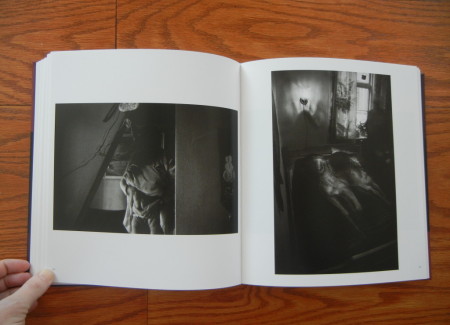

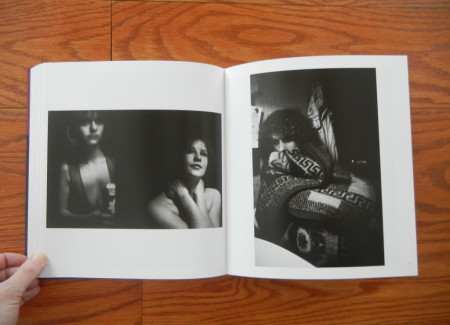

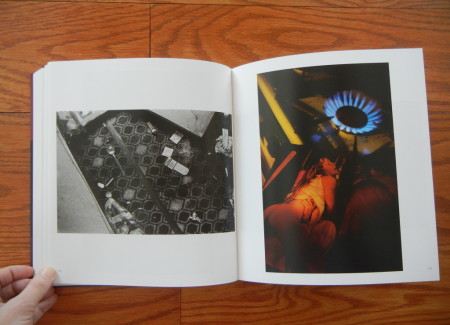

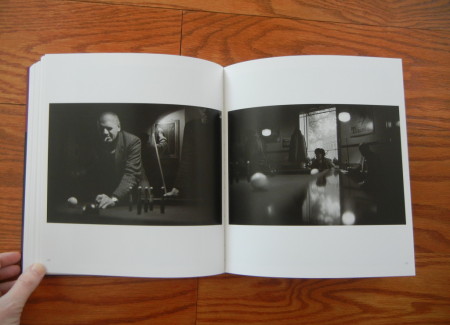

In roughly the middle section of the book, the decline of the neighborhood takes a much steeper turn, with the spread of seedy hotels and porn shops, the decay of the buildings, and a visible decline in foot traffic. Streets filled with nervous men, dirty snow, and simmering anger push Clement inside, where drugs and sex seethe in the dull squalor. While a few more explicit shots bring home the reality of the situation, most of his images are indirectly intimate – still lifes of used condoms, heroin spoons, and syringes, portraits of idling prostitutes and shadowy porn theater crowds, and glimpses of fleeting encounters and transactions under the illumination of a single bulb. A grim cloud of resigned hopelessness hangs over the whole neighborhood, the snowflakes seeming to fall with more despairing weight.

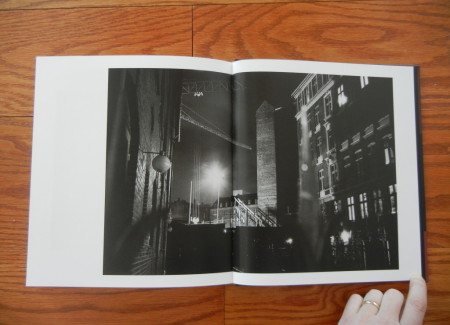

The final third of the book seems to work its way back to a reluctant kind of acceptance of what has gone on. Junk sellers colonize the sidewalks, the bars fill up, and a different mix of people can be found wandering the streets once again. The last few images actually feel noticeably lighter – boys joke around with an air gun, an impromptu play takes place amid hanging laundry, and drunken arguments seem just a little less hostile – it’s as if everyone has become more relaxed about the state of the neighborhood, or maybe things are turning up once again. Nature has overrun the theater, with wild greenery encroaching on the exit doors and back alley, and the arrival of the construction crane is a kind of symbolic metaphor for Clement’s nuanced tale – both an end and perhaps a beginning.

While Clement’s images inevitably jump around a bit across the decades, the narrative arc of the photobook is remarkably consistent, tying the whole span of time into a relatively neat if sometimes dispiriting package. What I like best is the way the unruly combination of photographic styles is woven together into one unified whole; we move from precise to blurred, from offhand to carefully composed, and from quietly documentary to emotionally expressive, all with masterful control. In many ways, this body of work is the opposite of the rigid project-based approach to photography that has become dominant in recent years. Over half a century, Clement has intelligently adapted his style to reflect story he wanted to tell, and as a result, the pictures are richer, more diverse, and more authentically full of life than any more tightly managed effort would have ever produced.

Collector’s POV: Krass Clement is represented by Banja Rathnov in Copenhagen (here). His work has little secondary market history, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.