JTF (just the facts): A total of 20 black and white photographs, framed in black and matted, and hung against white walls in the main gallery space and in the office area. All of the works are gelatin silver prints, made between 1968 and 1981 (most are vintage or near-vintage prints). Physical sizes range from roughly 7×9 to 9×13 inches (or the reverse), and no edition information was provided. (Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: The late 1960s and early 1970s were a particularly tumultuous time for photography in Japan. Even several decades later, the complete societal rebuilding process post World War II was still continuing, and the forces of encroaching Westernization, the Vietnam War, student rebellions, and countless other social movements and transformations were pulling the very fabric of the nation in opposing directions. One artistic outcome of this period was the are-bure-boke aesthetic, and the publications like Provoke that helped broaden its reach.

Kikuji Kawada’s 1965 project Chizu (The Map) was another critical photographic milestone from this period. It powerfully and expressively engaged with the aftermath of the atomic bombs and the cultural rutpures that were taking place, taking form as one of the landmarks of photobook history. As a follow up to Chizu, Kawada took inspiration from Goya, in particular his series of etchings from the late 1790s entitled Los Caprichos. Full of macabre scenes of witches, goblins, and other repulsions, Los Caprichos is a scathing indictment of the ignorance, decadence, and decline of Spanish society. Kawada resonated with Goya’s themes of illusion, delusion, and cultural illness, and set out to make photographs that took a new approach to documenting the unsettling realities he saw in Japan at that time. Most of the images on view here have not been exhibited since 1986, when they were shown at PGI in Tokyo.

The photographic Surrealism of the first half of the 20th century often experimented with distortion and visual strangeness, but Kawada’s rethinking of that approach (as inspired by Goya) takes that style to a much darker, more troubling, and more cynical place. His images aren’t playful games of found oddity or deliberate deviance, but are deeper meditations on vexing truths hiding in plain sight.

The show begins and ends with images of solitary swimmers. In the first, a woman glides away from us, her legs dissolving into a distorted flare of light, almost like she is breaking up in the water. And in the last, a man is squashed into a blob of head and elongated arms by the glimmer of the water in a swimming pool, his small form seeming eerily isolated in the expanse of water. In between, Kawada explores a selection of related motifs: shadows, isolated figures and objects, distortion/reflection, and scarier moments of fright and pain. Seen together, it’s a quietly harrowing vision of everyday Japanese life.

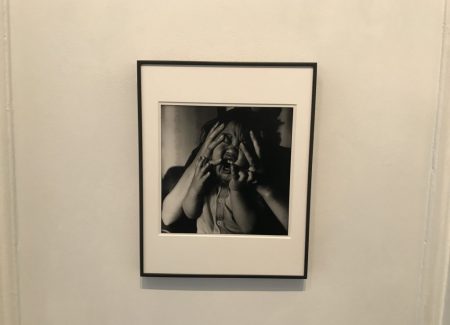

Luis Buñuel famously used a hand covered in ants to create a sense of prickly physical revulsion in his 1929 film Un Chien Andalou, and Kawada continues that feeling in his aptly titled Panic of the Ants image (from 1974.) The ants cluster and writhe in a frenzy of frozen action, and it’s hard not to see crazed confusion in their instinctual movement. This picture, and another of a screaming child whose face is being squished by two hands, immediately put the viewer on edge. Our wariness is then amplified by a rubber Godzilla stalking a building under construction, a wild jumping figure on a door shutter, and a single rubber glove floating in a rancid pond – on their own, these images might not seem entirely spooky or threatening, but in the context of this body of work, they’re positively haunting.

Other images use scale to enhance the feeling of isolation. A tiny airplane floats against the imposing dark clouds of a Tokyo fire, and a single white fish swims belly up (or is perhaps dead already?) in a swirling pool of dark water. Intruding shadows reverse that effect, adding a sense of creeping claustrophobia. Dark tree branches slither across an old tank monument, while a backlit newspaper reader becomes imposingly enlarged. And Kawada then notices city distortions that further tilt toward the unsettling, like a dissolving road arrow and a skewed dark sky reflection in a car windshield. It all adds up to a feeling of wanting to hide, which a man does behind the puzzling lines of a computer circuit board.

Perhaps our collective psyche at the moment is a bit too fragile for Kawada’s bitingly untethered uncertainty; if we’re grasping at smoke in the hopes of holding on to something substantial in the world around us, then these pictures won’t provide any comfort. At the same time, he has undeniably found a way to visualize a particular simmering mood, and that mood feels altogether resonant right now. These photographs crackle with grim intensity, the kind that sees a shade of horror in a drip castle at the seashore.

Collector’s POV: The prints in this show are priced between $8000 and $18000. Aside from the reselling of Kawada’s photobooks, there is little secondary market history for his work. As such, gallery retail remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.