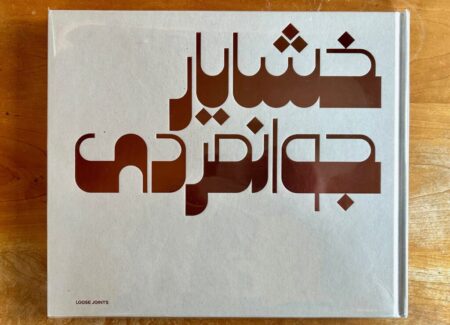

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2024 by Loose Joints (here). Hardback with debossed foil title, 285 × 245 mm, 96 pages, with 75 color photographs. Includes texts by Nathalie Herschdorfer and the artist (in English/Farsi). (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: It’s been more than fifty years since the journal Science published Garret Hardin’s infamous paper “Tragedy of the commons” in 1968. The essay’s basic thrust was that when people gain unregulated access to a finite natural resource, self-interest trumps group welfare, and the resource is degraded over time.

Hardin’s model has been borne out in countless examples. But it would be hard to think of a better case study than the Caspian Sea. Since the fracture of the Soviet Union in 1991, the world’s largest inland body of water has been buffeted by the competing agendas of five neighboring countries. To the south is Iran, to the northwest is Russia; Azerbaijan lies on the western shore, while Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan share the east. Throwing another geographical curveball into the equation, the Volga and Ural Rivers each drain thousands of miles from Russia’s heartland into the Caspian’s north end.

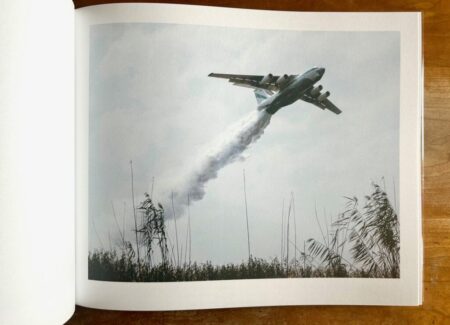

Besieged by unchecked development and splintered regulations, the Caspian Sea’s environmental prospects are dismal. The region is rich in fossil fuels. In fact the world’s first oil well was drilled near Baku, on the western shore, in 1846. Today refineries and production facilities are abundant, threatening local flora and fauna. The Volga River feeds the sea with industrial and biological agents, including petrochemical, nuclear waste, and sewage. As an endorheic basin, there is no natural outflow, so incoming pollutants have nowhere to go. Meanwhile, the water volume is declining due to consumption and evaporation. Fishing has decreased by 70% in recent years. Salinity is on the rise. By the end of this century, the Caspian Sea level may fall by 9-18 meters. All told, this tragedy of the commons is not a pretty picture.

The Iranian photographer Khashayar Javanmardi knows something about pretty pictures. He is also quite familiar with the Caspian Sea. He moved from Tehran to the city of Rasht on the Caspian’s southwest coast in 2004 when he was 13. His adolescence offered him a first hand seat to the region’s charms, as well as its dramatic changes. “It was a dreamy place,” he recalled recently in a CNN interview. “It was my utopia; everything happened for me at the Caspian.”

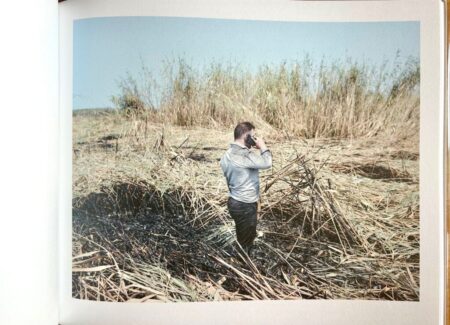

Javanmardi was smitten. When he studied photography in college, the Caspian Sea was a natural subject of interest. It eventually became a long-term project, paving the way to a photo career and resettlement in Lausanne, Switzerland. Over several years, he visited towns, harbors, and infrastructure along the sea’s Iranian shore, photographing people, buildings, and customs. The huge sea (Javanmardi prefers the more intimate term “lake”) is a constant watery presence in his pictures, both psychically and physically.

Javanmardi’s project was recently published in his debut monograph Caspian: A Southern Journey. The book’s design immediately locates the reader in Iran, with a Farsi title in modernist script adorning front and back covers. The interior photos follow a somewhat familiar 21st century photobook motif, blending portraiture, social documentary, and landscape in a carefully varied sequence. Unfortunately there are no captions to identify or contextualize the images, but two essays help to flesh out the basic concepts. Natalie Herschdorfer’s subheading captures their gist: “A photographic survey transformed into a cry of alarm.”

Herschdorfer sees the book as a clarion call, and Javanmardi would not disagree. But photo aesthetes will find here plenty to ponder as well. Caspian: A Southern Journey straddles the line between environmentalism and fine art. That is to say, it is part Rachel Carson and part Prix Elysée.

Killing these two photo birds with one stone is an admirable feat, and so some cognitive dissonance is only natural. “The evidence of [the Caspian Sea]’s decline is everywhere, an undeniable truth that can no longer be ignored,” Javanmardi proclaims in the afterword, with missionary zeal. “The death of the fish, the sorrow in the eyes of those who once looked to the sky with hope, all speak of a world growing darker.”

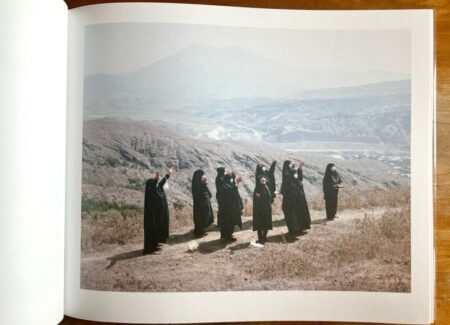

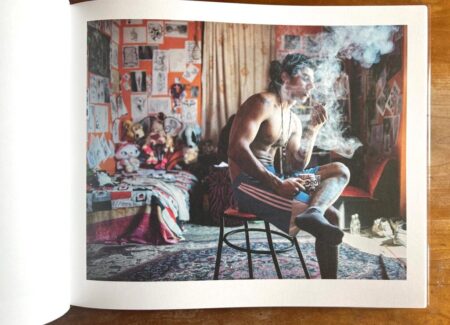

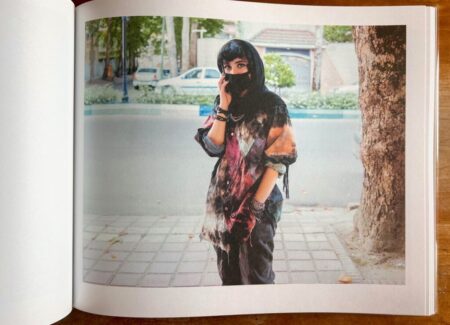

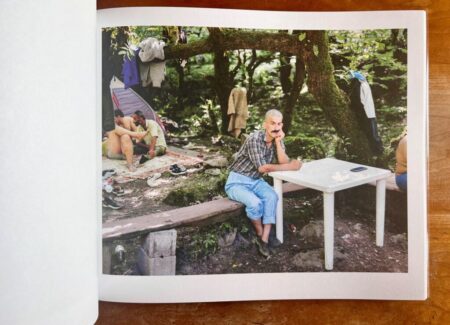

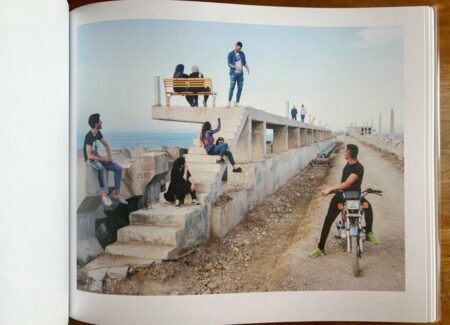

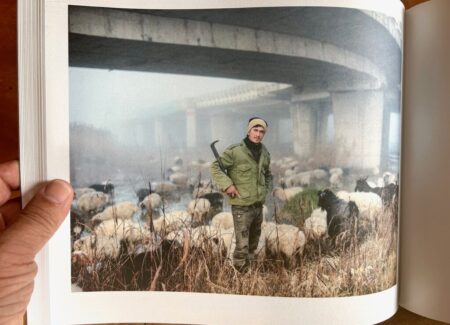

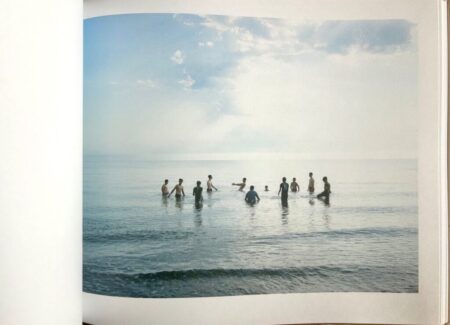

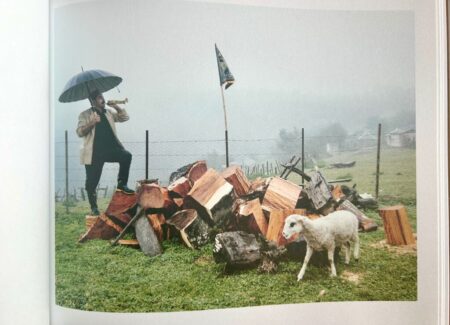

The situation is grim. Yet even as he sounds the alarm, Javanmardi’s photo brain can’t help seeking reverie. A picture of a bald man seated by an outdoor table isn’t exactly doomsday. Instead it evokes a mood of quiet contemplation. A motorcycle headlight probes lazily through fog in another photo, while another frame captures a goatherd tooting his trumpet near stacked firewood. Further along we see the Ayatollah’s face caricatured onto a grimy stucco wall. These scattered views into contemporary Iran are soothing and culturally informative, but they seem far removed from ecocide. In fact the two best photos in the book—one of a tattooed young man smoking in his bedroom, and another marshaling figures into candid form on a seaside wall—both feel relaxed and buoyant. Tragedy, what tragedy?

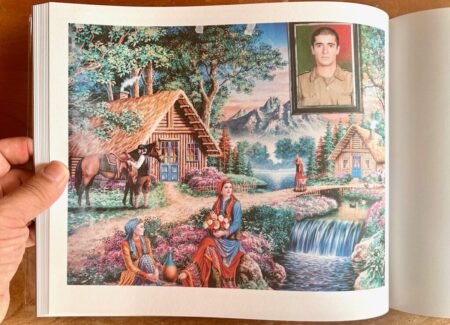

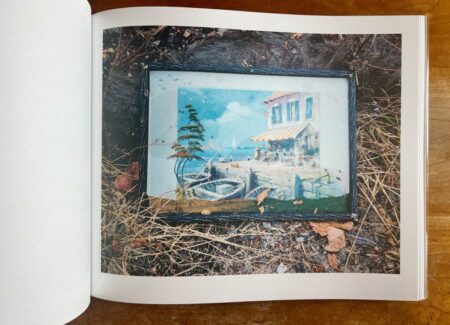

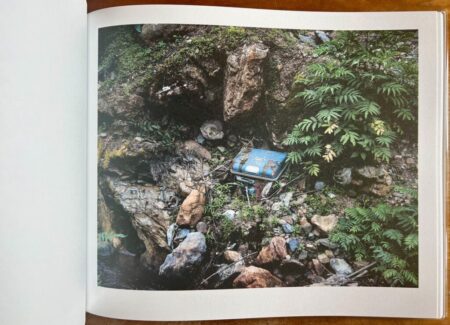

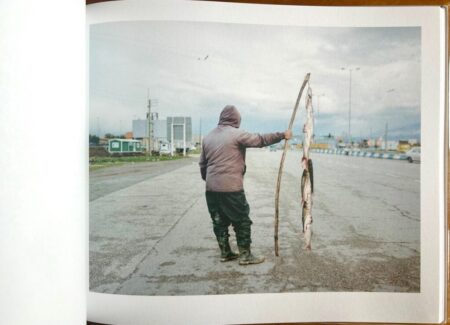

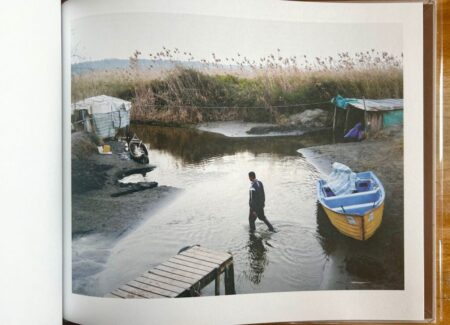

To be sure, hints of crisis provide a quiet subtext throughout. The Caspian Sea frequently comes into view. Whether cast as broad horizons or small water pockets, its mood is disquieting. A few pictures capture fishing boats, either outright beached or otherwise decommissioned. In one photo they are stacked in a harbor, with peeling paint to signal malaise. The image is nicely juxtaposed with another photo showing a quaint fishing harbor in an old framed painting. Still another frame shows a man selling a string of caught fish in a plaza. He and the painting seem to be running on spent dreams.

It’s not hard to put a nostalgic angle on such scenes. Javanmardi relishes his Caspian memories, even as the region hits a rough patch. The move to Switzerland must put a certain prism on past events. “For me this story is one of love,” he writes. “Even if, like all great loves, it carries within it, the seeds of inevitable sorrow.”

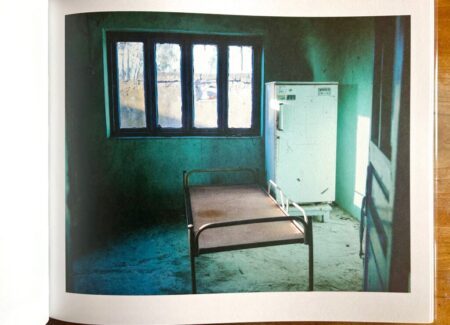

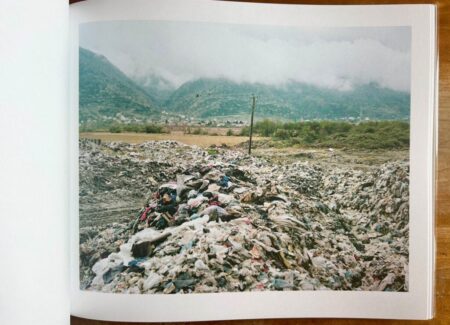

Try as he might, he can’t escape current conditions. When he photographs broad swaths of nature, his frames are inevitably impacted by humans, as in gorgeous photos of a blackened field, debris strewn pit, or burning vegetation. When he switches gears to photograph human structures, they are often rusty, decayed, or overgrown. Where does nature end and civilization begin? The categories blur like a shifting coastline.

Clearly not all is well with the Caspian. Yet life marches on, somewhat normalized. And Javanmardi’s photographic voice is oddly refined, even while witnessing hard times. He has an artist’s knack for composition, color, and light, with a tendency to aestheticize grim subjects.

The result is a book which lands a good distance from the unfiltered dystopias of Edward Burtynsky and Sebastião Salgado. It is a few degrees more beautiful, and less bleak. A closer comparison might be Chloe Dewe Matthews’ Caspian, published by Aperture in 2018. Or perhaps Richard Misrach’s Desert Cantos.

Like these predecessors, Caspian: A Southern Reflection is rooted in strong imagery. The picture making is solid enough that its tragedy of the commons might slip the reader’s mind, if just for a moment. But alas, the Caspian’s decline seems inexorable. No photobook is likely to stop it. On the plus side, at least from a photographer’s POV, there will always be more crisis to document. Javanmardi hints in his essay that Caspian: A Southern Reflection may be merely the first book of several volumes to come. Whether this starting point proves to be promising or pessimistic, we shall see.

Collector’s POV: Khashayar Javanmardi does not appear to have consistent gallery representation at this time. Collectors interested in following up should likely connect directly with the artist via his website (linked in the sidebar).