JTF (just the facts): A total of 14 color photographs, mounted and unframed, and hung against white walls in the two room gallery space. All of the works are archival pigment prints of digital constructions, made in 2016. The prints are each sized roughly 65×43, and available in editions of 3+2AP. (Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: One of the thorniest definitional questions of the digital photographic age is how we are prepared to think about and evaluate digital construction. In the analog world, we had (and still have) no problem with a photographer building elaborate set-ups for the sole purpose of photographing them (ask James Casebere, Thomas Demand, Vik Muniz, and countless others). Even when artists fudged a bit and started to use scanning and copying technologies (instead of cameras) to make images of their constructions (particularly in the mode of photocollage), we didn’t really cry foul. But when a contemporary photographer constructs something entirely in the digital realm (via software, 3D rendering tools, and other technical magic) and then “takes a photograph of it” (AKA outputs that final file as a photographic print), the purists in the group start to howl that we are no longer capturing light, no longer seeing the world though a lens, etc. It seems fully digital construction crosses a line that many folks are unwilling to accept.

Since the early 90s, Keith Cottingham has been only too happy to test these definitional boundaries. With projects spanning portraiture, archival reuse, architectural imagery, and nature photography, he has continually made photographs of things that didn’t exist, at least in a strictly literal sense – his work has leveraged drawings, wax models, digital modeling/painting, and fragments of other photographs as source material for a broad variety of complex photographic constructions.

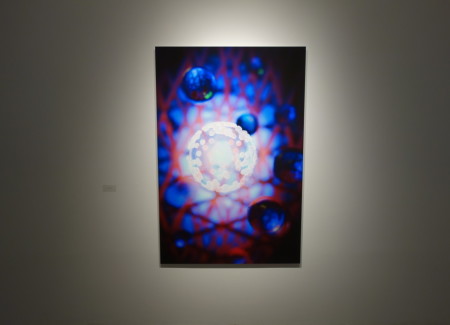

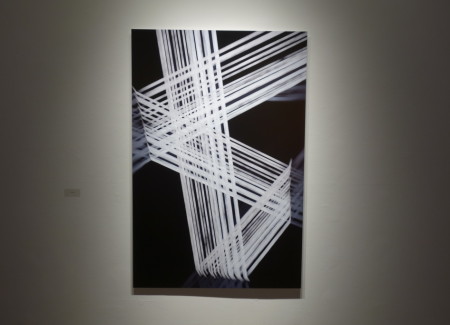

Cottingham’s newest pictures push further into the realm of quasi-scientific photography, where scale and time become harder to judge, and where the micro- and nanoscale topologies of biological systems start to look a lot like the light years of galaxies and cosmologies, at least in the ways that humans can visualize these complex systems. Using real world physics as his limiting framework, Cottingham has constructed 3D models and renderings that mimic the real, but have been abstracted beyond the point of specificity. While his works may bear passing resemblance to Harold Edgerton’s bouncing water droplets or Berenice Abbott’s intersecting wave forms, they are more conceptually related to something like Thomas Ruff’s zycles, where formulas and mathematics have been extended to become their own kind of art.

While it is intentionally difficult to distinguish between “small” and “large” in these images, forms that recall droplets, bubbles, and fluids of various kinds (some with tiny reflections inside) wander through the darkness, as do globules that might be something akin to cells decorated with surface proteins; the more regular geometries and striations feel like crystalline structures, or perhaps lattices of interlocked atoms. Flat planes covered in pinpricks of light go the other way and seem to imply the vastness of the universe, or at least polygons of space removed from the larger map and allowed to float in some kind of visualization interface. Regardless of the implied (or indecipherable) scale, most of these structures are lit with unlikely candy-colored light, heightening their sense of unreality, and in a few too many cases, crossing into eye-catching garishness.

To my eye, the intellectual questions that Cottingham’s pictures raise are more durably intriguing than the end result artworks themselves. If we take as a given that we will continue to extend photography to help us grapple with the mysteries of the hard-to-see, we have to come to grips with the fact that if we extend it far enough, we will need to define the place where it stops being photography altogether (at least in some bright line definitional way). And if we were comfortable constructing images in the analog age, we need to come up with new ways to measure and assess creative digital construction within the ever-changing boundaries of the medium. Cottingham’s visualizations boldly challenge our traditional assumptions about photography’s edges – and the exciting question that remains largely open is how we as a collective group of interested parties will (or will not) incorporate this kind of innovation into our working model of the art form.

Editor’s Note: For those who would place Cottingham’s newest digital constructions in the “not photography” camp, we encourage readers to use the comments section to explain your reasoning and where you might draw the line that marks the edge of the medium.

Collector’s POV: The prints in this show are priced at $12000 each. Cottingham’s work has little secondary market history, so gallery retail remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.

I am a photographer and have worked very hard on capturing, in camera, the “hard-to-see” reality that is happening but our eyes can hardly see in all its details. Where to draw the line is a difficult question to answer, but my inclination is to consider what is a purely digital construction as digital art, when paint and brushes are used it is a painting, where several mediums are used for creating the piece it is a collage and when photographic techniques are used, whether analog or digital, it is photography. I strive to capture and show the “hard-to-see” in an artistic way. You can google me, Haydee Yordan, and see my abstract in-camera images.

https://www.google.com.pr/search?q=haydee+yordan&client=safari&rls=en&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjZkdrztJjLAhVG7B4KHa4JAiMQ_AUIBygB&biw=1440&bih=722

The Ronald Feldman gallery site explains how the images are made, in that instead “of light photons revealing an outside world through a lens, these pure renderings go beyond photography to objectify 3D representations not tethered to real world referents.” The work is clearly relational to photography so I’m glad LK sees fit to review it.

And some ‘real’ photographers make images that don’t look anything like photographs anyway. Chris McCaw’s prints are a line incinerated across by light from the sun during an ‘exposure’ lasting several hours. And Alison Rossiter simply develops vintage photo papers – no camera or even a lens required. I actually think of them as ‘old school’ photographers : )

When the Photographer’s Gallery, London relocated to Ramillies Street it’s inauguaral show there in May 2012 was Ed Burtynsky’s ‘Oil’. Full on proper photography but it was soul-destroyingly unchallenging. I saw something later that day that I was wishing they had re-opened with instead – the installation at The Barbican, where Chinese artist Song Dong presented 10,000 of his mother’s possessions in a show called ‘Waste Not’. It was just a lifetime’s worth of stuff belonging to an old woman transplanted to a gallery situation. It was extraordinarily photographic in its effect.

I felt happy the other night when during a Gloria Steinem interview on BBC2 she was pressed whether she agrees with Germaine Greer that a transgendered M-F person should never be considered a woman, Steinem said “each person has the right to define themselves’. That sort of inclusivity appeals very greatly.

I hope LK will continue to review whatever he wants.