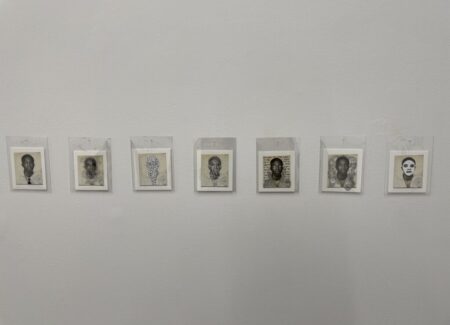

JTF (just the facts): A total of 322 photographic prints, made between 2012 and 2025, variously modified with ink, watercolor, paint, beads, sparkles, image fragments, and other objects, and displayed in clear plastic sleeves in the main gallery space and the office area. (Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: Of all the photographs that are routinely made year in and year out, passport photos are probably afforded the least artistic respect. Like the photobooth portrait or the police mug shot, these images typically feature a straightforward view of the head and shoulders of the sitter and are generally made against an austere white backdrop, but passport photographs go further in their intentional institutional blankness, prioritizing their primary function of defining the sitter’s place as citizen of a particular nation. A passport photograph is first and foremost a visual document of a neutral human face, used to prove personhood, and even when a smile sneaks in to enliven that visage, the numbing composition of the picture seems purposefully designed to drain its sitter of any animating individuality.

For those feeling secure in their national identity, a passport photograph is likely largely overlooked, or perhaps even generates a sense of mild embarrassment, in that it almost never offers a “good” likeness of its owner. But for those who are migrants, refugees, immigrants, or lingering in an in-between citizenship state, a passport photograph can be painfully symbolic of that tenuous position. In many cases, it is a visual reminder of a dramatic change taking place, a photograph of someone who once was, or who is in the process of becoming someone new, encompassing all of the fragilities and uncertainties embedded in that evolving personal history.

Keisha Scarville’s “Passports” project is an ongoing investigation of these possibilities found in the passport photographs of diasporic immigrants. In particular, Scarville has centered her project on a single black-and-white passport photograph made of her father, taken when he was 16 (in the late 1960s) as part of his process of migrating from Guyana to the United States. While Scarville’s “Mama’s Clothes” project (as seen in a 2022 gallery show, reviewed here, and her 2024 photobook, reviewed here) explored the grief-filled absence after her mother’s death by excavating the physical presence of her mother’s patterned clothes, “Passports” uses a different process of artistic reconfiguration to memorialize (and re-imagine) the presence of her father.

Starting back in 2012, and now totaling more than 300 individual works made intermittently in the passing weeks and months, the “Passports” project is a multi-year theme-and-variation exercise. Each work begins with a reproduction of the original passport photograph of her father, featuring a white open-necked shirt, shortly-cropped hair, and a blank expression on his face, set against a similarly white backdrop. In a sense, you could call the picture a blank slate, in that his emotional state is largely inscrutable – perhaps he is calm, or fearful, or eager, or weary, or anxious, or filled by any number of other moods and feelings at this exciting moment in his life, but the face he offers the world hold’s us at arms length. We might say it is incomplete, like a mask, or a fragment of who he actually was, which is where his daughter’s interventions enter the picture.

To say that Scarville has gone on to decorate or embellish each passport photo oversimplifies the situation quite a bit. For the most part, her process has been additive, with various mediums and objects added to the surface of the prints, but in a few cases, she has gone in the opposite direction, using erasure, whitening, and scratching as modes of interruption. Often, she has covered, extended, or enlarged her father’s face, creating a range of new personas and identities. In general, there is a sense of meditative artistic repetition to this process, of starting anew with the quiet passport portrait again and again and again, like a relentlessly personal search that offers new possibilities for discovery in each iteration. The resulting works have been installed in long lines that initially feel serial or sequential, that then burst outward into clouds of imagery that diffuse across the walls of the gallery space.

Ink, paint, and watercolor form the base for many of Scarville’s interventions and assemblages, but the list of her techniques and materials is surprisingly long for such a self-contained project. She has used collage to add printed imagery, photographs, and book plates to the works. She has added written, typed, and printed words as well as letter forms. And she has affixed tiny sparkles, glitter, beads, bells, mirrors, rings, twists of thread, stitching, gold leaf, puzzle pieces, googly eyes, and even a wishbone to the surfaces of the prints. For such small artworks, these composites are packed tightly with alternate aesthetic strategies, in some cases literally overflowing with aggregations.

Conceptually, Scarville’s father’s journey to America, and his new immigrant life to be led there, manifests itself as a long list of alternate personas – a boy, a man, a woman, a king, a saint, a superhero, an ancestor, and even an animal or two. Scarville actively wrestles with the complexity of his history, mixing images of African masks with American flags, whiteface, and moments from black history in the United States, forming an uneasy hybrid of assimilation. In some cases, his face becomes covered by an aggregation of symbols and images, while in others he is lost beneath a drapery of dots, stars, and other patterns. Often, Scarville keys in on his eyes, her overpainting or decoration riffing on ideas of vision, looking, and seeing, his eyes isolated and amplified into a penetrating stare. Still other works play with his mouth (and ideas of speech and language), or hairstyles, or variations of clothing, pushing and pulling her father in different directions. And while many of the resulting works have a celebratory or even an irreverent air, more than a few have a deeper undercurrent of melancholy and loss, mixing the father’s potential lives, aspirations, and narratives with the daughter’s sense of grasping at his identity.

In Scarville’s hands, her father’s passport photograph becomes an unexpected site for dialogue and interrogation, where she can attempt to reveal some of the hidden rhythms of his transformed life as a new American. In this way, an archival photo becomes something more like an icon or a talisman, infused with the energy of remembrance. In trying to think about these works from the other side, from the father’s perspective, Scarville’s project feels like the warm embrace of an homage, a message from the present that he is not forgotten and that the complexities and resonances of his life are still being considered. The daughter is still reveling in the potential of her father, even though many if not most of her artistic fantasies may be just that.

Collector’s POV: The entire collection of “Passports” is being sold as a single work (with any images previously sold in the process of being recovered so the set is complete), with the price available on request. Scarville’s work has not yet consistently found its way to the secondary markets, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.