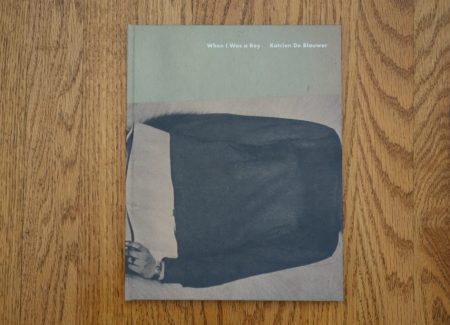

JTF (just the facts): Published by Libraryman in 2018 (here). Hardcover, 32 pages, with 27 color plates. There are no texts or essays included. In an edition of 500 copies. Part of the quarterly Seasons Series. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: While the digital revolution in photography has made it extremely easy to “stitch” together photographs and to assemble disparate images into one integrated composite, the results are nearly always perfectly clean and crisp. There are no rough edges, no above and below, no torn scraps or uneven glue, the hand-crafted effort of photographic collage removed entirely. Instead, it’s a point and click, drag and drop, resize and shuffle brand of image remixing, and this seamless integration (enabled by the pairing of digital source files and powerful editing software) has effectively generated its own new recombinatory aesthetic.

But in the case of collage, newer isn’t by definition better. The Belgian artist Katrien De Blauwer has steadily built her career by embracing just those features of physical collage that its new electronic sibling can’t match. She liberally (and thoughtfully) reuses printed imagery from a variety of sources, including newspapers, magazines, books, and other reproductions. She incisively cuts, tears, and divides photographs, but still allows small misalignments and remnants to remain in her compositions as reminders of a human touch. She builds up layers of overlapped imagery, using yellowed papers, salvaged scraps, and boards as her foundation, sometimes introducing lined paper, scribbled markings, or colored sheets. And she overpaints sections of her works, the gestural brushstrokes adding tactile color both “under” and “on top”. In short, she’s leveraging the overlooked strengths of an older working method to go artistic places that the new techniques can’t follow.

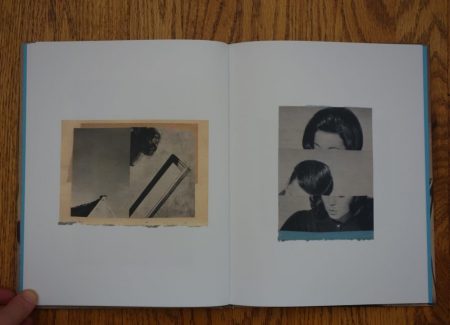

When I Was a Boy is De Blauwer’s most recent photobook, and its slim spine and small page count belie its sophisticated content. And while we might be tempted to reach all the way back to Hannah Höch or Kurt Schwitters to put De Blauwer’s work in art historical context, her closest stylistic relative (at least within the photographic collage club) is most likely John Stezaker. Both of their approaches eschew busy clustering and overworked accumulations, opting instead for the pared down simplicity of just a few images placed in exacting juxtaposition, where essences of framing and form provide all the freedom necessary to generate complex spatial relationships.

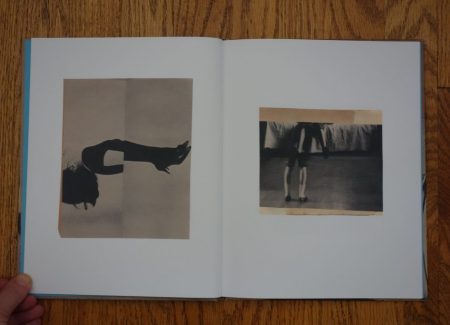

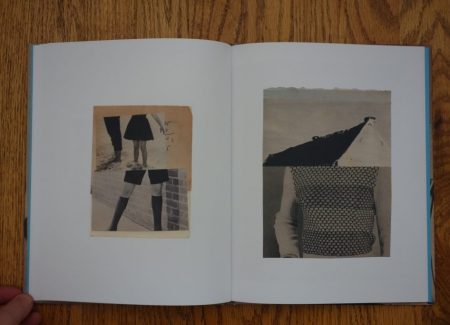

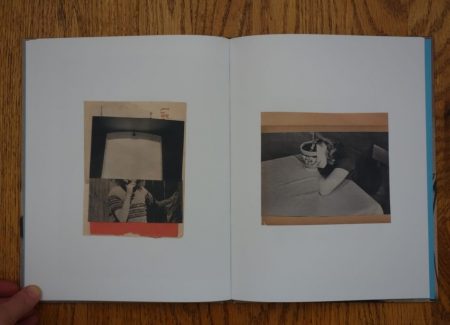

But while many of Stezaker’s collages communicate with a blast of disorienting directness, De Blauwer’s works are much more subtle and open ended, encouraging a more elusive and creative kind of interaction. For the most part, faces are removed and bodies are fragmented, turning an image of a woman (and they are mostly women in this gathering of works) into a feminine stand-in of sorts, where the curve of a shoulder, a pair of legs, or a slice of hair orients us but fails to deliver specificity.

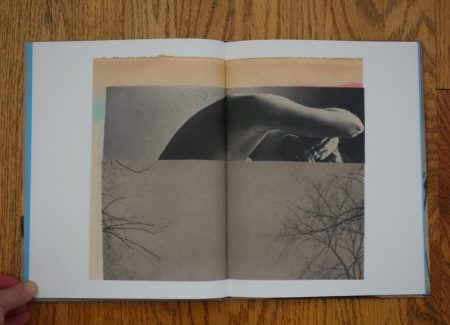

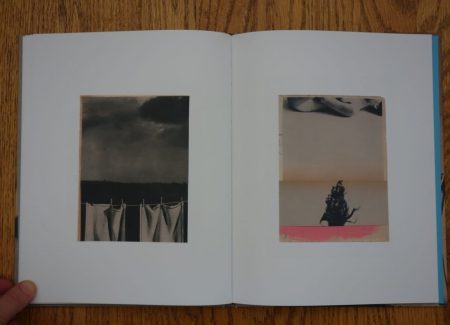

Without any obvious narrative hooks (aside from the allusion to gender fluidity in the book’s title), we are asked to pull back and reconsider the works in more formal terms, and this is where De Blauwer’s talent for managing compositional balance (and imbalance) shines. In many cases, echoes of shape and form, continuations of line, and faint similarities (like faded memories) provide the essential geometries that hold the collages together. Two unrelated hairlines sit on top of each other, like adjacent frames in a film strip. The same goes for two separate pairs of legs (perhaps of differing genders), although they have turned around (and hopped down from the bed) during the intervening flash of time. Just a few teeth in the mouth of a youngster become a repetition of the spots against a dark black background placed above. The sinuous line of a pulled-forward arm is echoed by the graceful bend of a tree branch. Another hairline connects to the semicircular arch of a steel bridge, and two mouths become a pair of expressive round circles. These visual ideas are simple and reduced to essentials, but surprisingly enchanting.

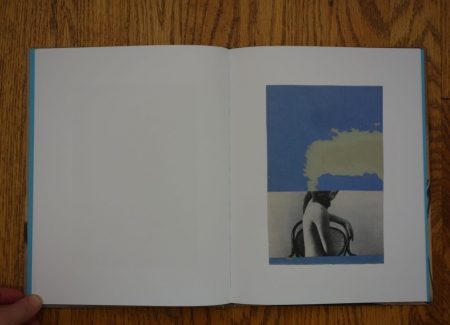

In many cases, De Blauwer uses painted brushstrokes to provide both a textural connection to nearby images and to create blocks of pink and blue (gendered colors, of course) that she employs in the balancing of abstract weights. A fall of shiny hair is extended by downward brushstrokes in both pink and blue, like a fork in the gender road. Long sweeps of color follow the directional lines of ruled paper. Shimmering thin wafts of color take the place of a head, like dissolving identity. An image of a child drawing with chalk on the sidewalk is flanked by textural movements in opposing colors. And just when we think the tiniest of color remnants might just be decoration, we notice that the brush of blue on one side of a collage is balanced by a sliver of pink on the other, the images in the middle providing a literal movement from one side of the composition to the other. De Blauwer’s choices are never random (including the blue endpapers), and when we pay close attention, these details gradually reveal themselves.

All of these intricate mechanisms allow De Blauwer to create compositions that feel effortlessly easy but show plenty of evidence of finely tuned proportion and control. The relative sizing of pictures, the nuanced management of black and white tonalities, and the precise arrangement and placement of pieces within the larger frame all contribute to the building up of intimate studies that brim with understated intelligence.

When I Was a Boy is the kind of photobook that seems smarter every time I look at it. With more time spent, I have noticed more almost imperceptible alternations of boy/girl, more formal echoes, clever spatial interruptions, and textural details, and more thoughtful connections, parallels, and hand-offs in the sequencing of the images. Seen together as an integrated artistic statement, the book flows with more aesthetic complexity than any single collage might normally offer, forcefully reminding us that De Blauwer has moved to a new level of synthesis and maturity with this impressive body of work.

Collector’s POV: Katrien De Blauwer is represented by Galerie Les Filles du Calvaire in Paris (here) and Gallery Fifty One in Antwerp (here). Her work has little secondary market history, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.