JTF (just the facts): Published in 2021 by Journal Photobooks (here). Clothbound hardcover (22×31 cm), 152 pages, with 86 color and black and white images. Includes drawings and paintings by Stickan Lundgren and texts by the artist in Swedish/English. Design by Jan Rosseel. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: In 2011, the Swedish artist Katinka Goldberg released her first photobook titled Surfacing, which poetically documented the bond with her mother and looked at how children are shaped by their parents’ vision of the world. This first book opened a trilogy that deals with identity, trauma, family, and belonging. Last year, almost ten years later, Goldberg released the second installment, Bristningar. The title of the book is a Swedish word which can be translated as a rupture, an explosion, an absence, or something more physical like a burst or a stretch mark. The new series is an attempt to approach childhood trauma and to deconstruct it. As she “explores the tension between closeness and distance,” Goldberg considers the feeling of alienation in one’s own body.

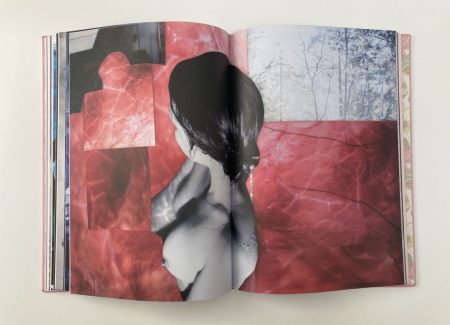

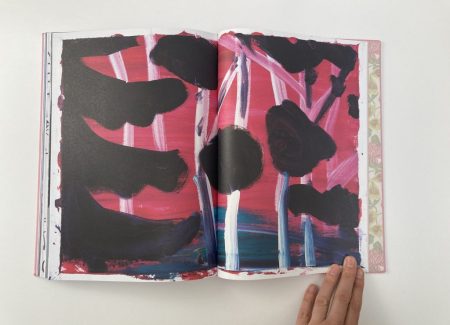

In Bristningar, Goldberg reconstructs, or rather restores, the world from a perspective of a child; she says that she made this book in a collaboration with her childhood self. To build the narrative, Goldberg combines painting, drawing, and photography, constantly pushing their limits. She uses her own photos, and occasionally materials from family albums. In her collages, she combines parts of bodies, often rearranging them in a new way, and this process of reassembling leads to healing.

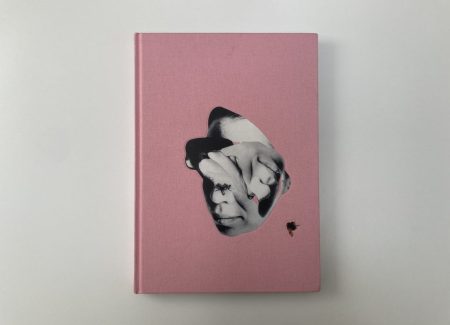

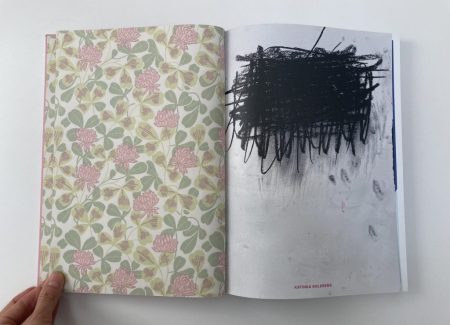

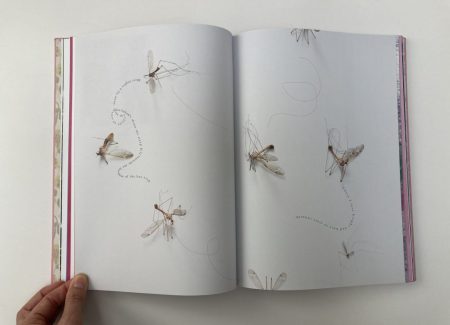

As a photobook, Bristningar is subtly elegant, thoughtful, and exciting. It has a pink cloth cover, a reference to the artist’s favorite childhood color. A collage of two faces, slightly debossed, appears in the center, and there is a fly placed nearby (insects are a common motif in the artist’s work). Inside, the narrative is built by mixing and layering photographs, drawings, collages, texts, cut outs, and shorter pages. The text is also very expressive, and playfully placed on the pages, adding more emotions and dynamism. The translated text in Swedish appears at the very end of the book, printed on a lighter pink paper.

While the first part of the trilogy examines Goldberg’s relationship with her mother, the artist’s grandmother is at the center of Bristningar. Goldberg depicts a partial upbringing with her grandmother, a woman who looked quite normal on the surface but carried a great deal of inner chaos. As Goldberg mixes and layers childhood writings, collages, paintings, and photographs, she creates a visual language that describes a child and a grandmother who are unable to connect, and this indirect language enables her to tell the story on her own terms. Bristningar functions like a diary, with page after page unfolding with the everyday undramatic violence of a child’s life.

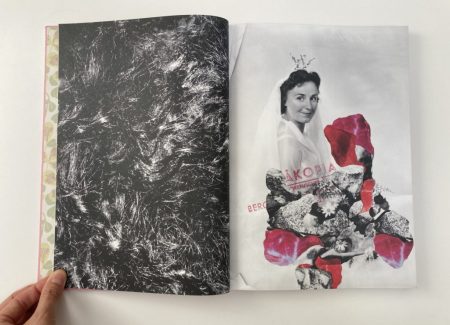

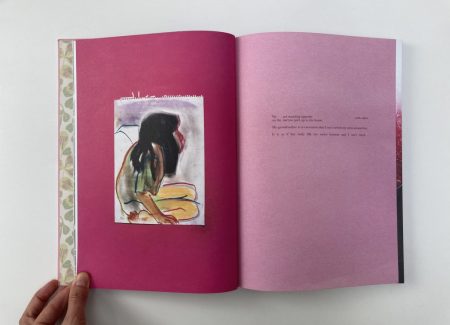

The first time we see the grandmother is in a collage – she appears wearing white clothes and a veil, and is surrounded by a pile of rocks mixed with flowers and red fragments that look like skin, meat, or leaves. This arrangement is paired with a close up of a dense tangle of hair. The grandmother has a self-satisfied smirk as she looks aside, and this is one instance where her face is not hidden or obstructed. A couple of pages in, a spread pairs a small drawing of the artist as a little girl sitting on the floor watching TV; this and other drawings in the book were made by the artist’s stepfather Stickan Lundgren. A short text appears on the right side of the spread, with part of it reading “my grandmother is so enormous that I can’t stretch my arms around her.” Both are placed against a pink backgrounds, slightly different in color.

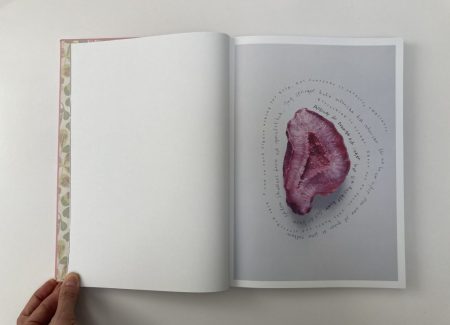

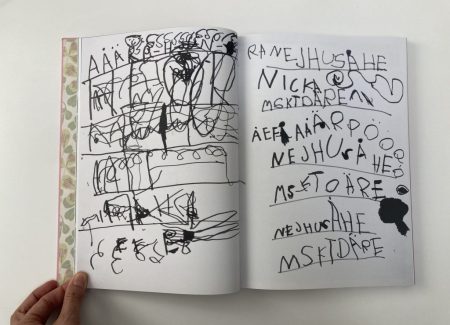

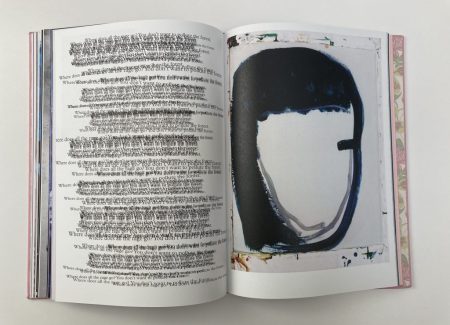

Throughout the book, Goldberg repeats certain colors and forms, and creates echoes through the juxtaposition of various visual elements. Her experimentation with text, written from the child’s perspective, is another exciting layer of the book. It functions as a narrative, but also as its own art form. A violet gemstone cut open showing inner crystals is traced by handwritten text in Swedish (and translated into English), reading “Everything is orange. There are no faces, only bones stretched skin. I run to each figure asking for help, but everyone is invasive emptiness.” Another spreads pair an abstract painting with a page that has the same line “Where does all the rage go? You don’t want to pollute the forest” layered over and over.

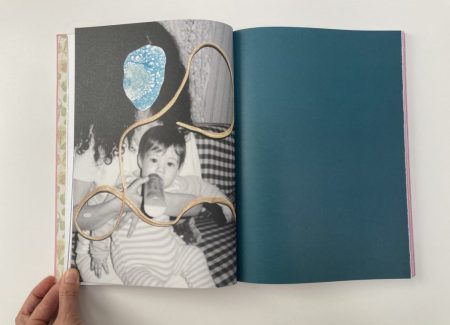

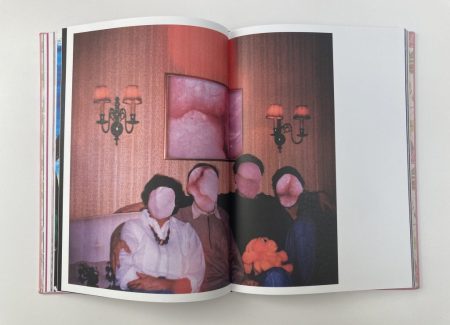

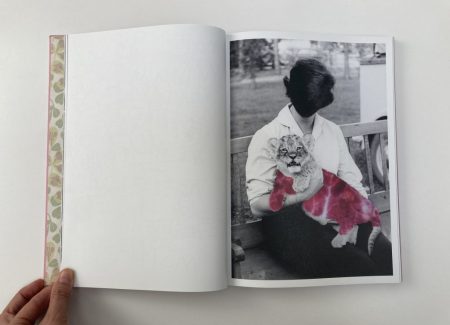

There is no simplified way to read Goldberg’s images. One striking black and white photograph shows a woman sitting on a bench – she holds a baby lion, and part of its body is covered again with patches that look like skin, meat, or leaves. She is faceless, with hair completely covering her head, so there is no way to connect with her; this is the artist’s grandmother in the 1950s. Another collage shows a portrait of Goldberg’s mother holding and feeding a baby (the artist) with a bottle, and again the face is replaced with a blue cutout, with the grandmother’s snakeskin belt placed on top of the image like an umbilical cord. Another horizontal photograph shows four people sitting on a sofa, but their faces (and the photo in the frame above them) have been replaced with pinkish fragments. Deconstructing and then reworking the images seems to have allowed Goldberg new possibilities for wrestling with her own internal demons.

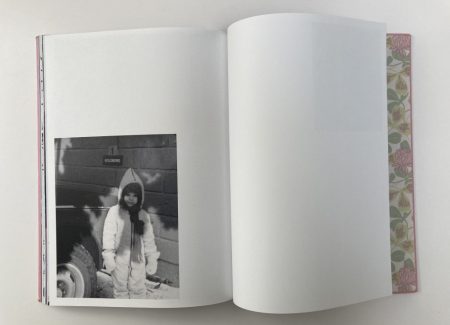

The elements of the book are sequenced together creating a certain intuitive rhythm, and forming an unpredictable and sometimes disorienting narrative. The book is dynamic and intense, while also offering a more restorative, healing element. One of the last photographs shows Goldberg as a child standing outside in a snowsuit, with a plank on the wall behind her reading “1 Goldberg” (for the nearby parking spot). Perhaps here, the story makes a full circle, finding its way to a kind of acceptance. Goldberg says that “what is important is that you work with the substance for so long that it becomes universal and is no longer about yourself.” Through its emotionally layered content, Bristningar shares the weight of childhood trauma.

A number of photographers have used the photobook format to share their own personal traumatic experiences. The Argentine photographer Mariela Sancari rebuilt memories of her father in her photobook Moisés (reviewed here). In Ký úc//Memento (reviewed here), Simone Hoang used an abstract narrative to reconstruct faded memories of her childhood while considering their limits. And more recently Linda Zhengová probed the depths of childhood trauma in her book titled Catharsis (reviewed here).

Bristningar is a certainly complex and exciting book to explore. The next and final book, Shtumer Alef, will focus on her family’s Jewish roots, and her material grandmother’s story fleeing to Sweden to escape the Nazis. It will look at how the trauma of war, when not addressed properly, can silently travel through the generations. Based on what Goldberg has already produced, it will be exciting to see the completed trilogy of photobooks together.

Collector’s POV: Katinka Goldberg is represented by Buer Gallery in Oslo (here) and NW Gallery in Copenhagen (here). Her work has not yet found its way to the secondary markets, so gallery retail remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.