JTF (just the facts): Published in 2020 by Triangle Books (here). Softcover, 220 x 280 mm, 40 pages, with 24 black-and-white reproductions. Includes an essay by Natilee Harren. Design by Olivier Vandervliet, copy-editing by Emiliano Battista. In an edition of 500 copies and a limited edition of 24. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: “I’ve always worked with my hands, and when I began to write, that seemed like handwork to me, as well. And I always thought of artists and writers as workers, at base, ultimately involved in the transformation of matter by hand.”

David Levi Strauss wrote these words in his preface to From Head To Hand: Art and the Manual, a collection of essays tracing the mutual influence between the workings of the hand and movements of the mind when engaged in the making of art. There is something daringly ancestral and quietly provocative in considering the (artist’s) hand as not merely a tool, but a quintessential organ for the transformation of ideas into material objects. Ancestral, because it stems from an awareness of lines and lineage, time and place, passed-down traditions and changing conventions; provocative, because it challenges the divide between art and labor, creation and craftsmanship, and the socio-economic structures that are embedded within. All of these notions seem to reverberate in Double Dominant, the latest (and beautifully made) book by Karl Haendel.

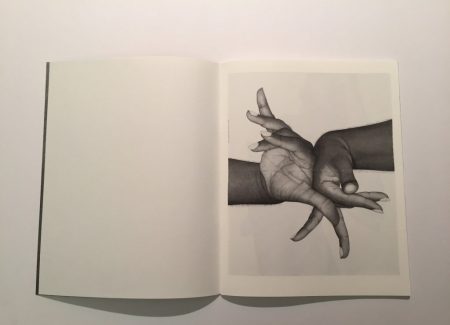

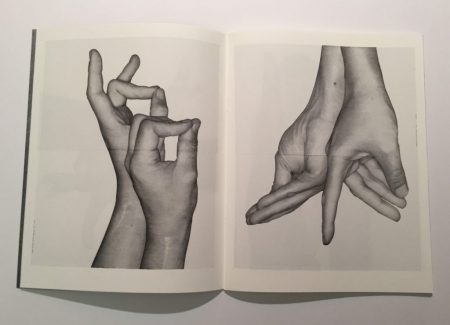

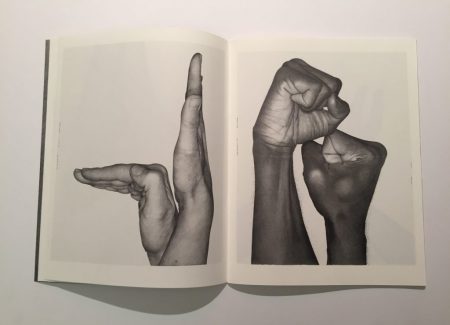

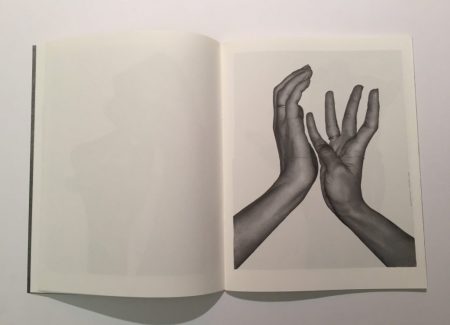

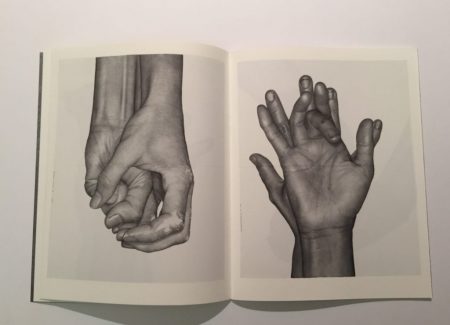

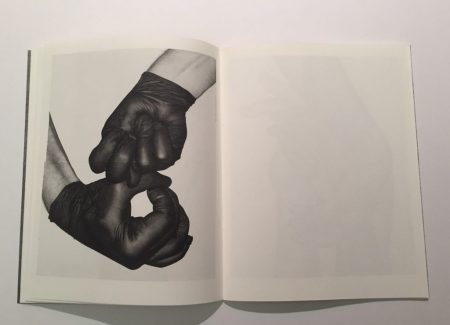

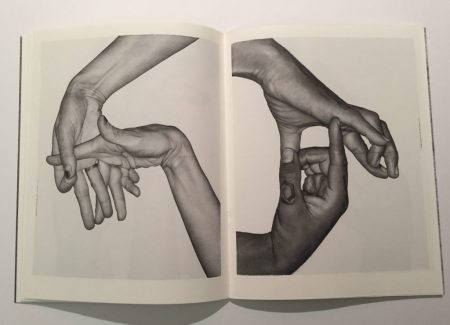

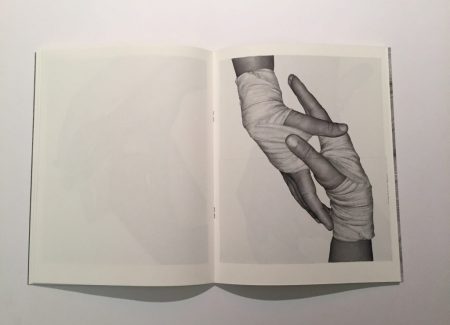

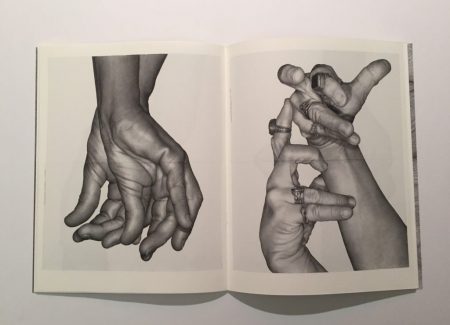

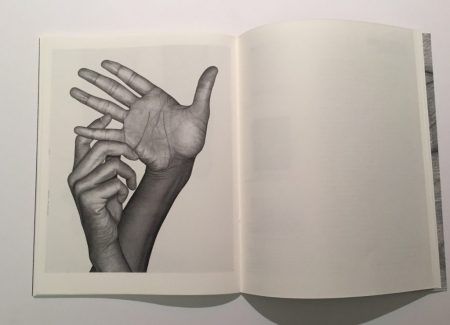

In it, Haendel presents twenty-four monochrome images of artists’ hands. They belong to friends and colleagues he admires, including Walead Beshty, Asher Hartman, Candice Lin, and Kerry Tribe, to name a few. The images’ spell is instantaneous. Freckles and creases, hairs and nails – long or short, manicured or messy – grab your attention unobtrusively, without competing. The plain hands are as beautiful to observe as those marked by paint or scars, covered by bandages or rubber gloves, adorned with rings or tattoos. One or two pairs to a spread, the hands (which are at times smaller, at other times slightly larger than life-size) often appear like dancers frozen in a complex choreography of a pas de deux. Corralled by a soft-grey background and set against the thick, cream-colored pages, we see fingers squeeze and bend, clench and flex, point and push, rubbing and pulling away, then barely touching or almost caressing. Perhaps most elegantly captured are those of Miljohn Ruperto, whose elongated fingers (their posture) remind me of the manual impersonation of a peacock I once watched as a child.

They exert a bizarre fascination, these hands. It’s like watching something on the brink of explosion. All of them speak through their gestures and expressiveness, hovering somewhere between intimacy and remaining ungraspable. They reveal and conceal simultaneously, as any great portrait does. The word “composure” comes to mind. And it is this composure that, the longer and closer you look, doesn’t quite add up.

This is probably the moment I should mention that Haendel’s images, despite their appearance, aren’t photographs but large-scale drawings of photographs. A deception I didn’t notice – until I began to see the fine marks on the bottom and top of each drawing, as if indicating an orienting grid. This deception, however, does not only pertain to how Haendel’s images are made, but also to what they depict. The book’s title alludes to this intervention.

Haendel made his first Double Dominant drawing of Emily Mast’s hand, now his former spouse (who is also included in the book). “I was thinking about intermingling my touch with hers – a kind of shared tactility and intimacy,” he has written. When the drawing was finished, Haendel realized that “the interplay of touch, intimacy, and power that got [him] to that first drawing was likely not going to transmit to the audience.” What felt more exciting instead was the hand’s presence as a portrait – a portrait of an artist, made by another one.

“I make art with my dominant hand, and I can represent another artist through the hand that they make their art with. Using my time and labor to honor another’s labor, be it physical or intellectual,” he describes, “is a kind of a service or an homage.” The project began.

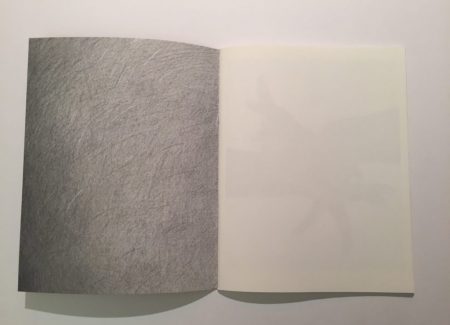

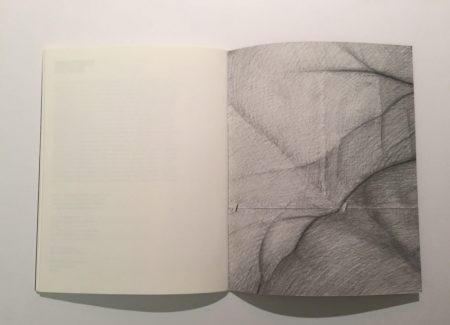

Haendel visited most of the artists featured in Double Dominant in their studio or at home, where he took several photographs of their dominant hand. Back in his studio, he digitally crafted a composite image comprised of two iterations of the respective artist’s hand that Haendel and his studio assistants subsequently drew in a monumental scale. Considering the book’s intimate size, the actual drawings must be mesmerizingly immersive, possibly overwhelming in their tactile impact (the book’s endpapers, each showing an enlarged, almost abstract fragment of skin, give an impression of this experience). This may feel like a loss.

I wonder, though, if this difference in scale (and, therefore, in perception) allows for the book and the images within to engage the viewer in a different dialogue than when standing in front of the large-scale drawings. A dialogue that bridges the supposed schism between drawing and photography and how we see and perceive the images they produce. Historically, the photograph has been considered a frozen record of an event (unfolding between the photographer and what is photographed), while a drawing, for its very materiality, is considered to contain the experience of looking; it is at once an act of discovery and questioning.

Unable to discern Haendel’s pencil strokes, hatchings, shadings, and wavering lines, I look at the book’s images in the way I look at photographs – I focus on details and the possible meanings they may carry. I discover and question just as much. Even though all of these images are inscribed with the names of their sitters (scribbled to the side and printed in the back of the book), I am surprised how many of them feel rather ambiguous in terms of gender, age, and race. I think of femininity and masculinity, of how we construct them socially, economically, politically, and how quickly these constructs reveal themselves as such, even crumble – when all we see is only a fragment. My questions change with every page.

Were the scars I see caused by an accident or self-inflicted? Do they hurt when the weather changes? Do some of these artists bite their nails (possibly a sign of anxiety?) or did they just break while working? How do we distinguish self-care from vanity from obsessiveness? Are only those married who wear a wedding band, and what do they think of marriage in general? Does being single or not matter for the art they make? What are they currently working on and what exactly is the relationship between their hands and their work? What do their hands reveal about their minds, the way they process ideas?

In scope and premise, Double Dominant stems from and continues a long, multifaceted history of artists making images of hands, which Natilee Harren’s wonderfully rich and superbly written essay retraces in the book’s final pages. You may think of movements, like the Renaissance, Modernism, Conceptual Art, or of individual works, such as the Gargas cave paintings; Auguste Rodin’s Cathedral, a sculpture carved in marble of two right hands spiraling into an almost-embrace; Richard Serra’s video Hand Catching Lead; or John Copland’s manual self-portraits. Among Haendel’s most intriguing references that Harren points out, are Joe Goode’s L.A. Artists in Their Cars, a calendar featuring photographs of Goode’s social circle of artist-friends – and Silvia Kolbowski’s installation of separate video and audio loops titled An Inadequate History of Conceptual Art. While the video shows close-ups of hands belonging to the pioneers of conceptual art, the audio features their descriptions of works and their authors, without mentioning titles and names. What makes Haendel’s work different, is the fact that is doesn’t represent a defined social circle or the members of an artistic movement. As one of his more personal bodies of work, Double Dominant certainly provides insights into Haendel’s friendships and creative affinities within LA’s contemporary-art world, stretching from the early 2000s, when he arrived in the city, to the present. What resonates most, however, is Haendel’s tangible respect for these hands and the people they belong to.

“I don’t fetishize artists hand or their touch,” he writes. “I fetishize their minds. I primarily keep the company of artists because the way they see the world excites and perplexes me.”

The hands that Haendel photographs, then draws, are portraits of artists, of hands that make art – of hands that carve, dance, draw, paint, perform, type, write – among many other things. They are hands that work, hands that think. They exist in the same place, at the same moment.

Collector’s POV: Karl Haendel is represented by Vielmetter Los Angeles (here), Mitchell-Innes & Nash in New York (here), and Wentrup Gallery in Berlin (here).