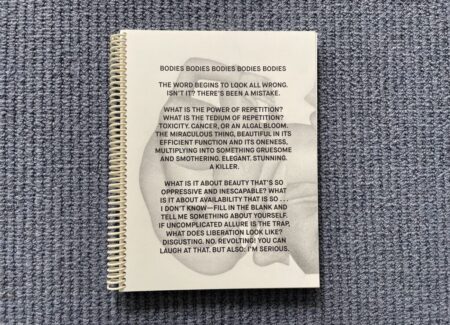

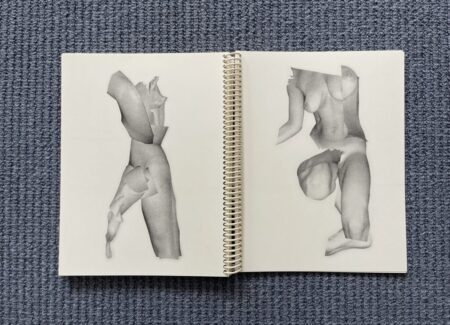

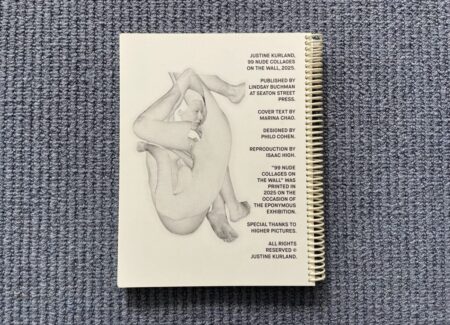

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2025 by Seaton Street Press (here). Coil-bound Risograph-printed softcover, 10.75 x 8.25 inches, 100 pages. Cover text by Marina Chao. In an edition of 200 copies. Design by Philo Cohen. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Back in 1991, the British publisher Jonathan Cape released a book of female nudes made by Lee Friedlander in late 1980s, matter-of-factly titled Nudes. The nude female form wasn’t a subject that Friedlander had spent much time with previously, having largely built his photographic reputation in the 1960s and 1970s with street scenes, TV screens, landscapes, and oddly engaging self portraits. But as the decades clicked by, the voracious Friedlander eye kept reaching out, extending its gaze to a dizzying range of subject matter: portraits, people at work, gatherings at parties, flowers in vases, the desert, formal gardens, trees, public monuments, his wife Maria, chain link fences, words and letters, views from rental cars, national parks, even fashion. And almost regardless of the subject that found itself in front of his camera at any one moment, Friedlander’s signature vision would chop up the visual raw material, push in uncomfortably close, twist the compositional angles, and interrupt and rearrange the available forms with a consistent degree of visual brashness, humor, and energy that were uniquely his own. While the content was different from image to image and decade to decade, the style of seeing was almost always immediately identifiable as Friedlander’s.

Given the long history of the female nude as a subject, particularly as seen by the Modernist photographers a few decades earlier, it might seem like Friedlander would have had a hard time finding his own way to see the nude form with originality, but as it turned out, his nudes were indeed boldly and radically different, so much so that they were polarizing to those that saw them. Some concluded that he was simply doing what he had done before, bending bodies in unusual directions, using flash to amplify curves and angles, and generally seeing these women dispassionately and abstractly, as anonymous forms to wrangle into unexpected and often deliberately awkward and unbalanced compositions. But others were altogether uncomfortable with (or even actively disliked) the pictures, both because of the inherent imbalance of a 50-something year old man (at the time) making images of nude young women in the privacy of their own apartments, homes, and bedrooms, and with the degree of objectified explicitness that Friedlander’s images seemingly embraced (or at least took for granted), in terms of the intimate closeness, spread legs, pubic hair, and crotches invasively placed in plain view. In a contemporary world now more willing to call out the leering of the male gaze, even some thirty years later, Friedlander’s nudes remain charged, provocative, and up for unresolved debate. But amid that back-and-forth, interest in the pictures has been consistent – the original Nudes photobook has since been reprinted three times, and a new expanded version (titled A Second Look: The Nudes, published by DAP) was released in 2013, with a cover quote by former MoMA curator John Szarkowski hailing the “qualities of generosity and openness” in the pictures, and highlighting the nudes as “simultaneously carnal and friendly”. But let’s put Friedlander’s photobooks back on the shelf for just a moment, and I’ll come back to that unlikely last turn of phrase a bit later.

A handful of years ago, I can imagine Justine Kurland standing in front of her own massive bookshelf, staring up at all the accumulated names arranged there and pondering how those influences had shaped her trajectory as a successful mid-career photographer. Kurland got her MFA at Yale in the late 1990s, and so it was effectively impossible, given that particular time period, for her to have avoided studying, knowing, and absorbing the work of Lee Friedlander and the many other now famous artists who came up in the generations before her; her shelves were likely groaning from the weight of those many photographers, most of whom were white, male, and heterosexual. As it turns out, Kurland was at a pivot point in her own life and artistic career, and so decided to more actively try to wrestle with and unravel those aggregated masculine influences.

Kurland approached this conceptual problem with a surprising degree of cathartic physicality – she got out from behind her camera, pulled down the offending books from her bookshelves, and started to literally cut them up, creating new collages out of the excised imagery. Each book by a previously canonized male photographer was wholly reinterpreted, deconstructed, and reassembled into Kurland’s own reclaimed reconsideration of the original imagery; in a sense, she reprocessed all her influences (sometimes savagely and destructively), thereby making more room for the emergence of her own point of view and commentary. Her project ultimately took shape as the excellent 2021 photobook SCUMB Manifesto and an associated gallery show of the collages (reviewed here).

And perhaps not unexpectedly, Kurland’s artistic rage found particular traction with Friedlander’s nudes. While many of the books in her library were transformed into individual SCUMB Manifesto collages, Kurland ended up adding a handful of works derived from Friedlander’s Nudes to the final edit of the book, including several overlapped studies of bodies, an homage to Jay DeFeo, a work spelling out the letters of her own name JUSTINE, a totem of vaginas, a vortex of dark pubic hair, and a fold-out poster that aggregated the fragmented female bodies into an astonishingly dense and churning whirl, which she also placed on the book’s cover. It seems she was particularly provoked by (or furious with) Friedlander’s work, and so came back again and again to try to liberate the bodies from his gaze.

In the years since, Kurland has continued to make collages, in a few cases making artistic trades with male artists (or their publishers), their contributed books repaid with her collaged reinterpretations of their work. Last year, she showed an extended series of floral collages constructed from William Eggleston’s multi-volume set The Democratic Forest, which she named her “SCUMB Flowers” (as seen in a gallery show reviewed here). The scope of that publication allowed Kurland to dig much deeper, leading to more than two dozen new collages from the same source material.

But like a burr under her saddle, it seems the Friedlander nudes just wouldn’t go away, the duality of attraction/revulsion they offered Kurland seemingly undimmed by the passing years, even after she had already turned them into an initial series of collages. So she traded copies of SCUMB Manifesto for the visual raw material Friedlander had made and went to work again, ultimately crafting dozens of small collages of the extracted bodies, presenting them as a massive installation at Astor Weeks Gallery (link below) and in this unpretentious photobook.

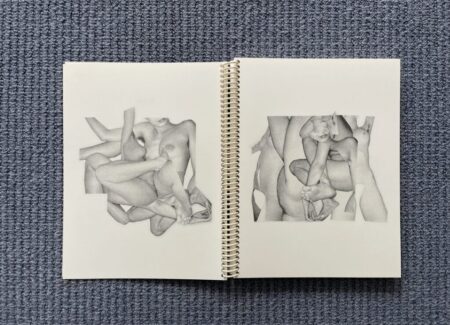

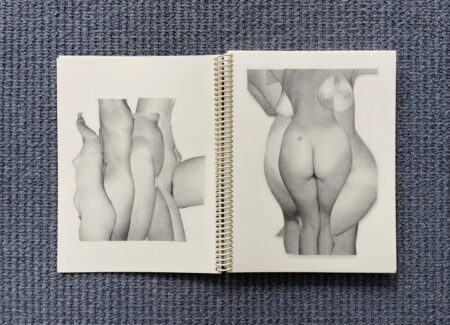

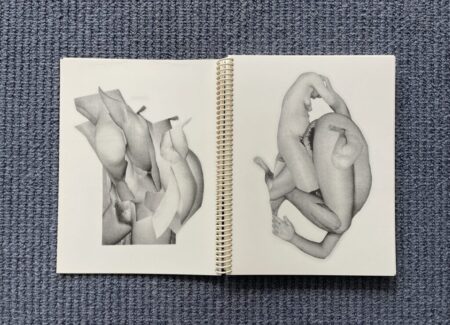

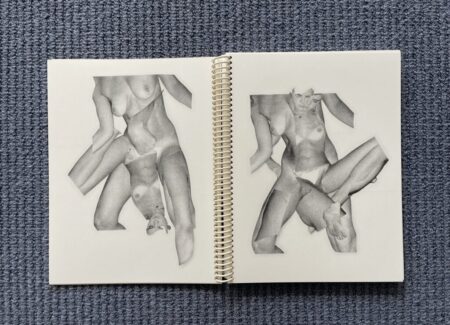

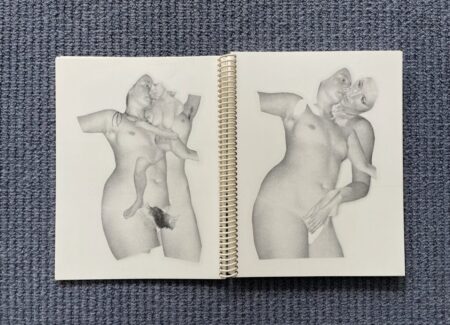

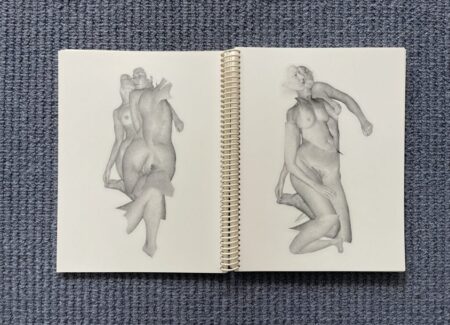

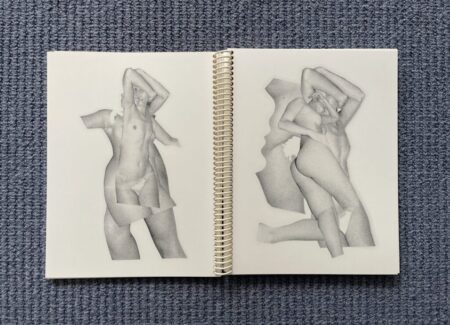

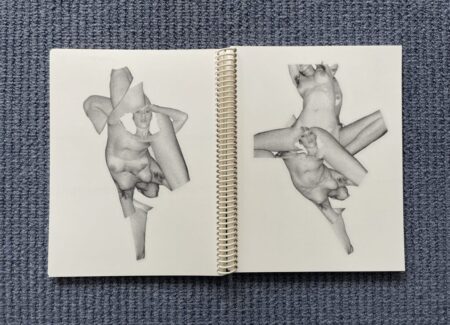

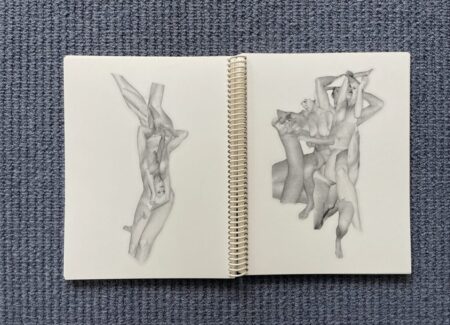

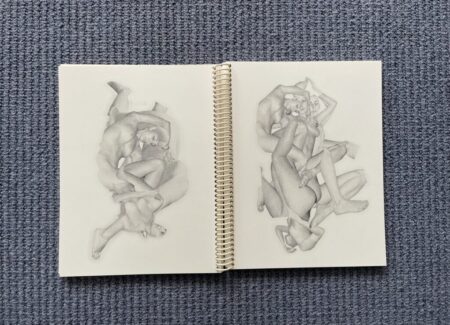

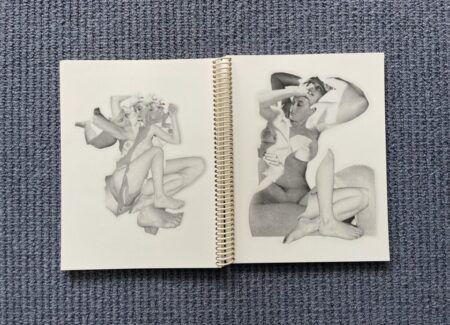

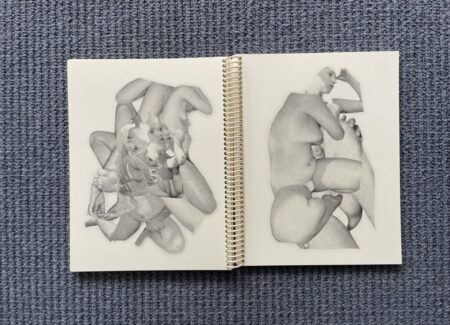

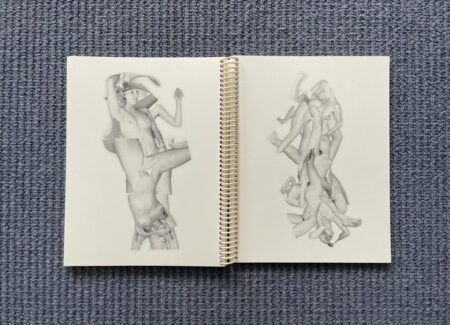

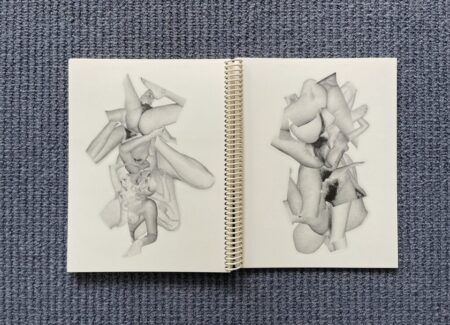

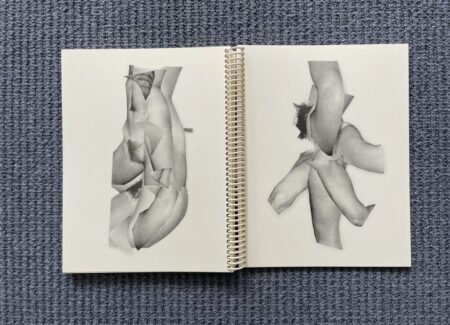

All of the nudes in these new collages have been exactingly decontextualized – that is, the surrounding rooms, beds, and other furniture that Friedlander originally included have been largely cut away, as have many of the identifying heads, leaving behind anonymous female bodies, which Kurland has then layered on top of each other in overlapped gatherings of arms, legs, breasts, butts, and other body parts. While there is often quite a bit of dense overlapping going on, in general, the compositions feel minutely controlled, with each body placed precisely and interactions between bodies organized to deliberately create formal harmony or friction.

This is a thick photobook, with single collages placed on both sides of the spreads, and for some reason, I can’t get out of my head a kind of booming schoolmaster voiceover repeating “again!”, and “again!”, and “again!” (perhaps with a smacking of a ruler on the table), exhorting Kurland to make yet another collage, to keep repeating the exercise, to get it right. The relentless repetition of this process feels central to this artistic exercise, and as the pages turn, we see ideas start in one college, and then evolve into the next, and the next, and the next, the exact same Friedlander figures pushed further and further from their earlier existence.

There is a mercilessness to this activity, or even an obsessiveness, that will likely make some viewers uncomfortable, and the piling up of scattered and discarded bodies can feel troubling or almost horrific, which is I think partially the intent. Kurland is amplifying the idea that Friedlander’s original gaze (overtly or not) asked these women to contort themselves for the pleasure of the camera, in a process of submission. Kurland hones in on the worst of these offenses – the bent over views, the arched backs, the blasted flash, the crotches served up – and multiplies them out into repetitions that give no ground. We can say that the abstracted (or erased) female bodies have been in a sense reclaimed, but the process is not without injury and trauma. Friedlander’s vantage point is emphatically refuted and discarded, but this liberating dismemberment and redefinition is often brusque and ruthless.

After spending time with Kurland’s collages, when we return to the Szarkowski pull quote of “carnal and friendly”, it seems all the more ridiculous, and obliviously distant from what Kurland sees in the same pictures. Her fury at the sexual objectification embedded in the heterosexual male gaze is palpable, but at some level, I think she knows that however much she reprocesses the images, she can’t entirely free them from their history.

Many of the collages employ a deep understanding and sophistication in terms of form. Some make visual jokes, parodies, and echoes, while others twist and transform the essence of the implied attractions, rearranging faces and recalibrating desire to include the agency of women. By simply changing the angle or orientation of a model’s gaze (or turning one face toward another), the perceived intent of the poses can be altered. Kurland also re-places hands and raised arms with incisiveness, reorienting the gestures of touch, caress, restraint, or power. Insightful stacking is also taking place, with one awkward pose topped by another, making each one all the more obvious in its ungainliness. To my eye, if you can acknowledge the inherent aggressiveness and violence of Kurland’s collages, there are indeed formal graces to be discovered underneath that harsh veneer. But as the pages turn, there is no avoiding the accumulations that feel neither carnal nor friendly.

As a writer wrestling with how my own white male heterosexual gaze becomes part of this discussion, what these collages do is push me to understand better how a nude can be a commentary, and to see more clearly that even the photographing of a body abstractly brings with it an objectification that carries its own baggage. I think Kurland’s collages amplify these realizations, but also push back to more fundamental issues of who is allowed to look or see, and how desire and attraction can be included or separated from images of bodies. What I feel most in these collages is intense frustration – at how stifling the objectification of the male gaze can be for women and how much effort it takes to try to break those bonds.

Both the original SCUMB Manifesto photobook and this new book have placed provocative almost shouting messages in all capitals on their covers, as if to wake us up. Here one line says “If uncomplicated allure is the trap, what does liberation look like? Disgusting. No. Revolting!” This idea – and the Kurland collages that embody it – has stuck with me. Maybe beauty has to be better revealed as ugliness to rebalance the scales. There is indeed some gruesomeness to be found in 99 Nude Collages on the Wall, but the fact that Kurland felt so strongly that these collages must be distressing is certainly worth thinking about some more.

Collector’s POV: Justine Kurland is represented by Higher Pictures in New York (here). Kurland’s work has slowly begun to enter the secondary markets in the past few years, with prices ranging from roughly $2000 to $6000.

This body of work was recently on view at Astor Weeks Gallery in New York (from April 2 to May 17, 2025, here), as a 99-part mural, with individual collages removed as sold. The collages were priced at $199 each. (Installation shot above.)