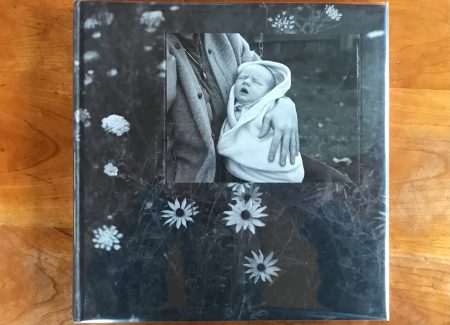

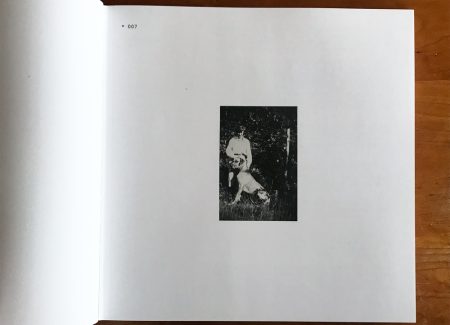

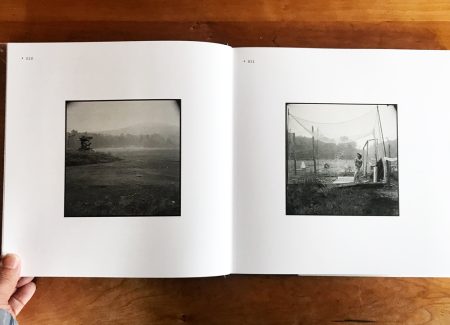

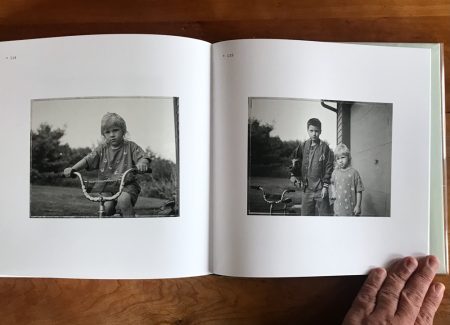

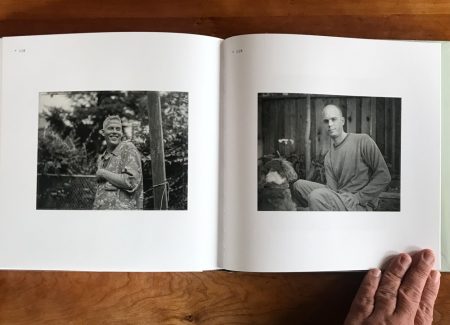

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2021 by Stanley/Barker (here). Three-quarter bound hardback with tipped in cover photo (250 x 250 mm), 128 pages, with 101 monochrome photographs. Includes an introduction by the author. Designed by The Entente. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: It’s been several months since Judith Black’s Vacation was published last June. If this review has taken some time to reach fruition, perhaps that’s fitting. All of the photos in this book—shot between 1981 and 2004—have marinated in the shadows for a while already. So a little longer won’t hurt. In fact it might help, since pictures often ripen with time.

This line of thinking is central to Judith Black’s work, which is rooted in family, aging, shifting relationships, and long term thinking, and thus often aimed in the rear view mirror. She has applied an historical gaze to picture albums, women photographers, and self portraiture of all types, including found photos and vernacular snapshots by others. But her primary focus—and the subject of Vacation—is her own family as lived, witnessed, and shot by herself over the course of decades.

Black’s website comes with a gauze of history too. It doesn’t appear to have been updated in a decade. But its raison d’être still feels current. Under the simple heading Why, she explains “since 1979, I have been making images of my family that serve as a touchstone for memories…Future generations might look at them to reconstruct a story of their fore-bearers. Others might see something of their experience in them. The photographs are actual physical memories, evoking stories, truths and lies, all of which are ever changing depending on the reader’s perspective.”

In a case of life imitating art, Black’s career has also followed the model of buried archive, albeit not entirely by design. She gained important belt notches following her MFA in 1981. Black earned a Guggenheim in 1986, was published by Aperture Magazine in 1987, and was then curated into MoMA’s blockbuster Pleasures and Terrors of Domestic Comfort by Peter Galassi in 1991. This exhibition pulled a variety of family and home-based photography from the shadows, showcasing a previously overlooked genre and conferring mainstream legitimacy. It was right up Judith Black’s alley, and her work fit seamlessly alongside Sage Sohier, Jo Ann Callis, Doug DuBois, and other contemporaries.

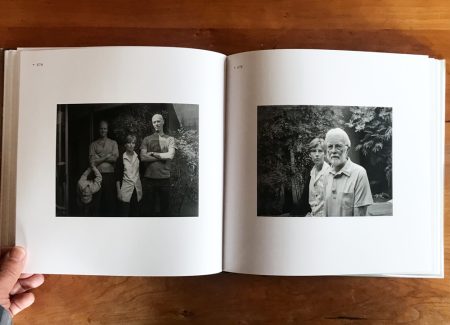

With MoMA’s feather in her cap she continued to photograph, but the trail of recognition gradually grew cold. It wasn’t until 2020 that she entered the spotlight again with Pleasant Street by Stanley/Barker—the London publisher who has developed a cottage industry unearthing neglected oeuvres. Vacation is the successor to that monograph and a companion piece of sorts, with virtually identical approach, timeline, design, and physical specs. But there is one key difference. Whereas Pleasant Street featured Black’s photos from her Cambridge, Massachusetts home, Vacation gathers her impressions of the world beyond. This is family life as encountered in the great wide open, a deliberate expansion of the domestic territory.

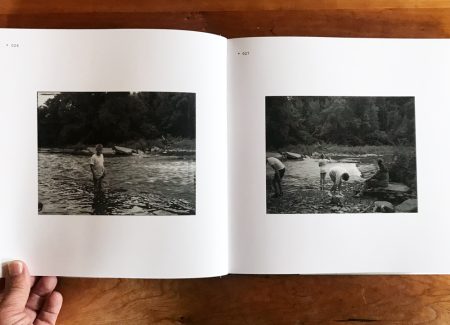

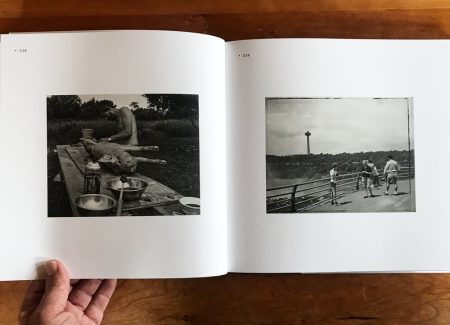

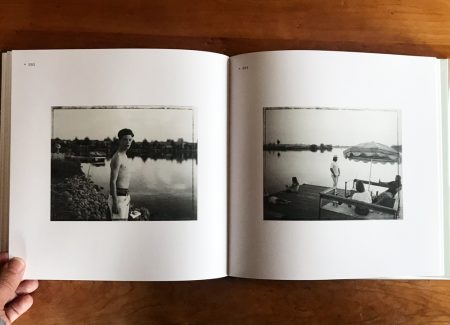

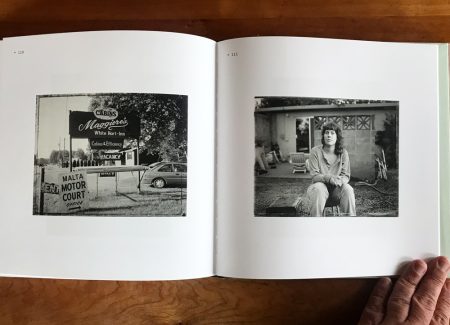

Vacation is rooted in a single road trip, a 6-week cross country jaunt in 1986. With Guggenheim funding in hand, Black bought a station wagon, packed up her kids and camera equipment, and headed west. Spending all that time in a car with four children may not be everyone’s idea of a vacation, but for Black it was a break from work stress, and well timed for summer frolics. This was her chance to undertake the classic travelogue which had been a staple of American photography—Frank, Winogrand, Shore, Sternfeld, et al. But unlike her predecessors Black aimed the wheel at extended family. No murky bars, gas stations, or city streets for her. Instead she dropped in on friends and relatives enjoying their summer, sometimes staying for a few days, photographing the whole while.

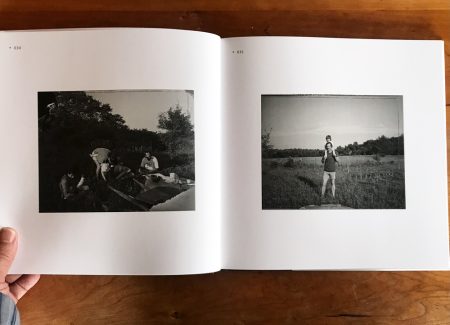

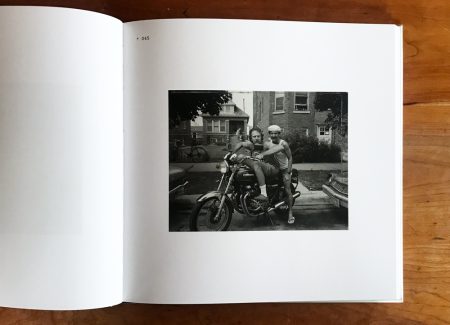

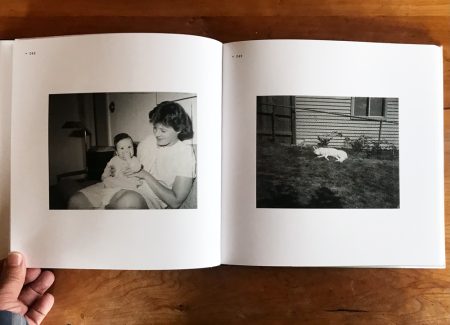

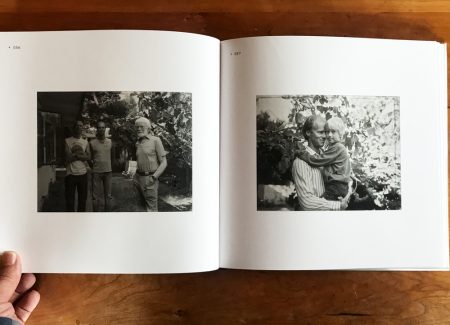

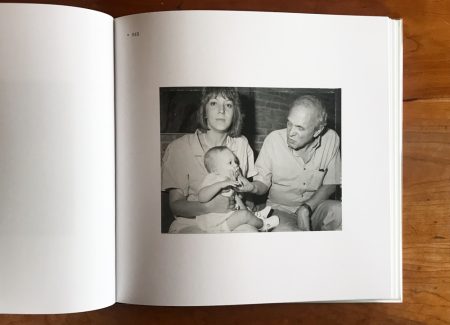

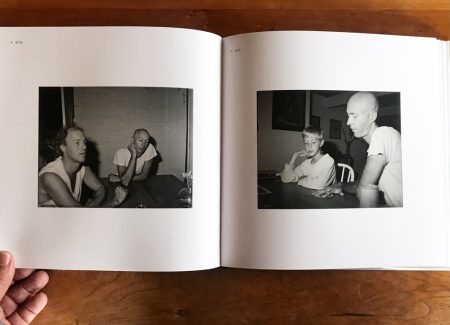

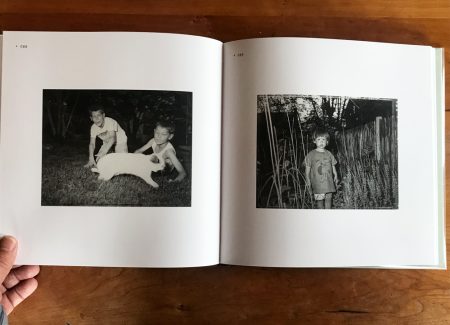

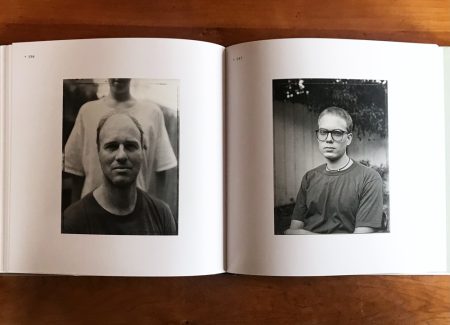

Her primary tool was a 4×5 view camera loaded with monochrome Polaroid Type 55, a peel-apart film producing positive (presumably gifted to subjects) and negative (archived by Black). The format’s distinctive processing artifacts mark the borders of most photos in this book. It’s a signature look which enhances their bygone character, and is also rather beautiful in its own right. Black’s cumbersome view camera typically meant posed portraits using a tripod, and many of her portraits capture subjects gazing back dutifully, waiting patiently for the click. But Vacation also exhibits a surprising degree of spontaneity. A snapshot of Diana, Miki, and Angie feels fleeting and off the cuff. Another photo of the family laughing as it surrounds Aunt Christine around the dining table has a spur of the moment vitality. The ephemeral nature of these and several other pictures is enhanced with bold flash. Many scenes will be familiar to those who’ve made a family road trip: kids looking bored in a park, wrestling for attention, or mugging from the beach. Today they might be snapped with an iPhone, but without the gravitas of Vacation.

Photographs from that 1986 journey form the core of the book, comprising its middle third. But since this is a study of the family tree, its chronology extends roots and branches to other dates. There are a few photos from before 1986 and several dozen more from years to follow, including subsequent road trips. Along the way we encounter Black’s relatives, in shifting iterations of themselves. There are her road-tripping kids Laura, Johanna, Erik, and Dylan, her husband Rob and his family Lynne, Milt, and Christopher. Black’s Aunt Christine makes an appearance, along with her father, stepmom Gaye, and their extended family including Phil and son Cody. Her brothers Jon, Hank, and Hank’s son Christian are photographed several times. And let’s not forget her sister Maggie and son Matt. Along the way many others make an appearance, their relationships unspecified: Jeff, Devon, Jim, Peg, Anna, Diana, Miki, Angie, Tanner, Max, Aki, Eileen, Jake, Willie, and Sophie. Hovering in the background of several photos, and sometimes coming to the fore, is Judith Black herself. At the time of her self-portraits the word selfie did not yet exist. But the basic urge to affirm one’s presence is eternal.

Did you catch all of those names? Don’t worry, you won’t be tested. But it is a lot to remember. Jumping into the book is a bit like walking into a stranger’s family reunion. You don’t know anyone at first, and it’s natural to feel somewhat lost. But Vacation is even more confusing than reality, because it captures these family members over a 23 year period. Faces and bodies change over time, especially those of young ones moving through adolescence. When we first encounter Erik, for example, it is 1982. He is a tow-haired boy of around 10. Captured near the end of the book in 2004, he has matured to full adulthood. It takes a few back-and-forth page flips to confirm that yes, it is indeed the same person. Multiply that example by several dozen identities, locations, and genetic permutations, and piecing this book together becomes more work than vacation.

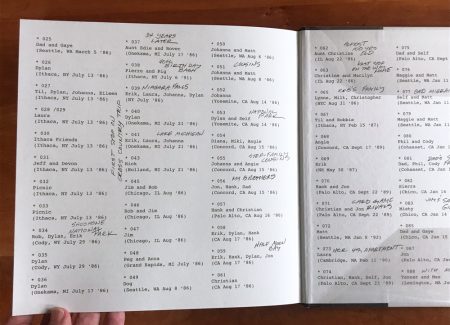

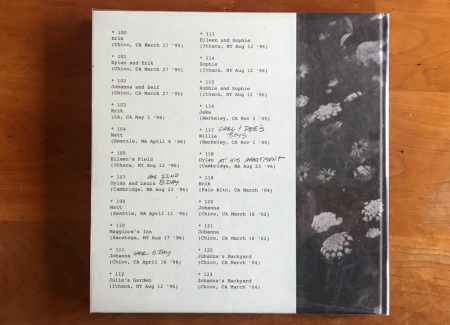

Fortunately Vacation comes with a Rosetta Stone. A rear index captions the pictures by name, place, and date (the sequence is chronological). This list is quite useful. There will be more page flipping involved, as the reader sorts out just who is who, but it does not detract much. The index is not merely invaluable for decoding content. It’s a distinctive design feature in its own right. As in Pleasant Street, the captions are typewritten, with various handwritten annotations and corrections. They spill through the green endpapers and across most of the back cover. Perhaps they are a facsimile of Black’s original notes? Or they might be a clever adaptation. In any case they lend the photos an improvisatory coda. Capped by analog scribbles, the preceding pictures take on a sketchbook quality, and a certain road trip breeziness, bouncing from place to place.

Before Vacation (and Pleasant Street), Black’s family archives had not received much attention. The photos exist on her website, but organized there quite differently, and without recent updates. So it is nice to see them collected in published form, under a motif —vacation— that hints at both idleness and adventure. It comes at a time during global pandemic, when vacations have become rather precious, and domesticity reinforced.

Each of Black’s exposures captures a special moment, a static point in time. Meanwhile the broader world of pictures has shifted radically since she made them. Lines between private and public have blurred. Photographs that might have been previously confined to family albums and shoeboxes are now shared openly online. That includes selfies, food photos, kids on a playdate, vacation snapshots, beach scenes, birthdays, reunions, and all of the other subjects found in this book. They may not be commonly captured with the same care and skill as Black’s pictures but personal photos crowd the field alongside Vacation. Domestic scenes and selfies bombard us daily. What does it mean to shoot one’s own family? Why take the summer off and travel great distances to perform an act repeated billions of times daily?

When Peter Galassi curated Pleasures and Terrors of Domestic Comfort, the answers to those questions were quite different. He offered a window into an insular world, which has since blown wide open. Vacation puts the reader back in 1986 for a moment, an era when each family picture was a small treasure, and you might have to drive a thousand miles to see what a relative looked like. Representations of domestic life have shifted since then, but the power of good photos remains constant. Vacation would have been a worthwhile book regardless of publication year. That said, the long wait has only enhanced its appeal.

Collector’s POV: Judith Black does not appear to have consistent gallery representation at this time. As a result, interested collectors should likely follow up directly with the artist via her website (linked in the sidebar).