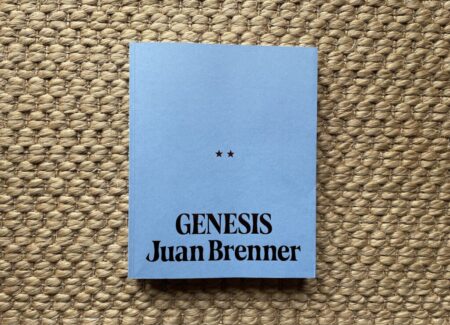

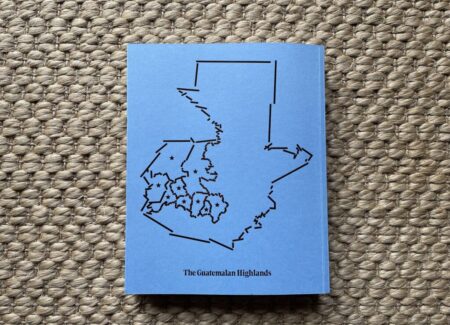

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2024 by Guest Editions (here). Foil embossed gate-folded soft cover, 210 x 260mm, 360 pages, with 259 images. Includes an essay by Julio Serrano, a conversation between Gem Fletcher and the artist, and a full index of image plates and descriptions. Design by Thomas Coombes. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Juan Brenner’s photobook Genesis is a multi-layered multi-year photographic study of contemporary cultural and societal change, as seen in the Guatemalan Highlands. To wrestle with transformation photographically, moments that are captured by the camera at a specific time and place need to be put in a larger context, where we can then reflect on what any particular instance means when considered as part of a broader and more expansive view of local history. In many cases, change doesn’t announce itself boldly or prominently, waiting instead for someone to notice the tiny details that are in flux, the ones that document the nuanced frictions between past and present and the unlikely hybridization of the old and new ways of living.

As compared with the tight conception of Brenner’s earlier photobook projects – Tonatiuh from 2019 (reviewed here), which explored the legacies of Spanish conquest and colonialism in Guatemala, and The Ravine, The Virgin, & The Spring from 2020 (reviewed here), which dug into contemporary urban life in Guatemala City – Genesis is much more wide-ranging in its scope and ambition. Made relatively concurrently with those other two projects, the photographs in Genesis were gathered in repeated road trips up into the mountains and rich valleys of the western Highlands region between 2018 and 2022. The resulting tome is thick and weighty, stuffing over 250 images into its visually dense investigation of the shifting complexities of the Highlands people and their changing culture.

The long term factors influencing the cultural development of the Highlands are many and varied, going all the way back to the Mayans and their domination over indigenous Mesoamerica. Of course, the Spanish invasion of Guatemala in the 16th century and the resulting colonial systems significantly rebalanced the power structures in the region, transforming language, religion, and other social structures. In the most recent century, democracy, capitalism, and the narco trade have entered the Central American picture, supercharged by technology. The combination of all these layered histories and forces has created what Brenner has called a “multiverse”, where the contemporary realities in the Highlands are intricately interwoven with traditions from the past. Led by the younger generation who are coming of age in an increasingly connected world, the Highlands are once again undergoing a “process of becoming” something new.

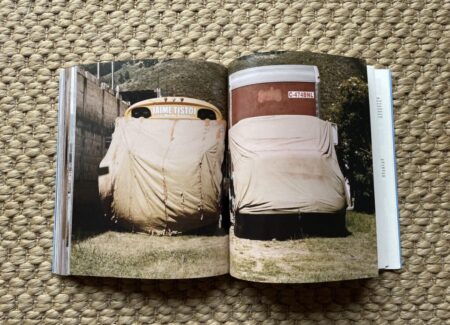

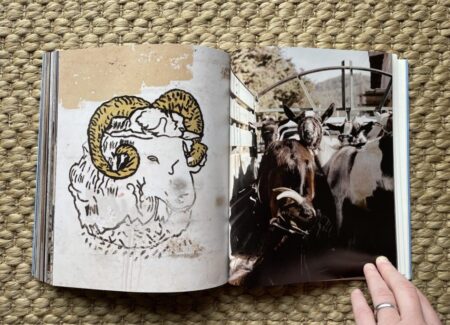

In visually exploring and mapping the Highlands, Brenner consistently encounters anachronistic mysteries, dualities, and contradictions which he then uses to fill his frames. Unlikely juxtapositions of progress and destruction, tradition and globalization, and ancient knowledge and new technology fight for presence, and differing signals and symbols of power are repeatedly intermingled, jumbling the way these codes can be read and interpreted. This leads to an overall mood of evolving regeneration, and a continual jostling in the coexistence of competing cultural hierarchies and systems.

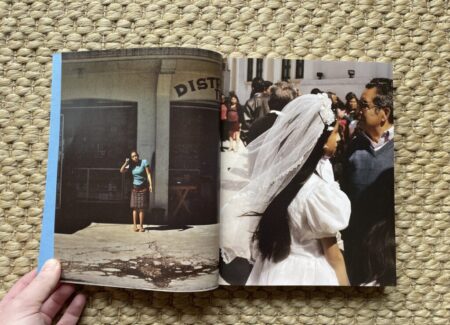

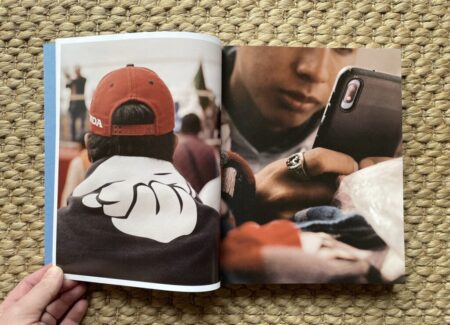

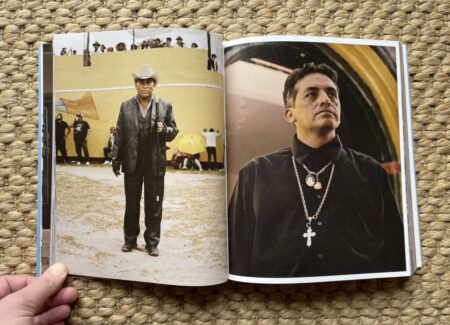

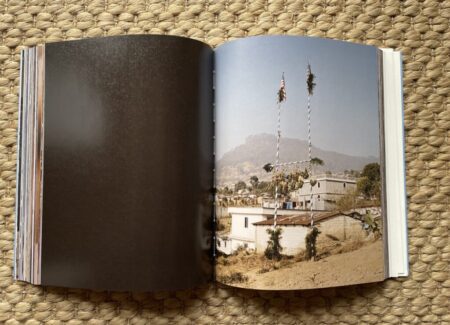

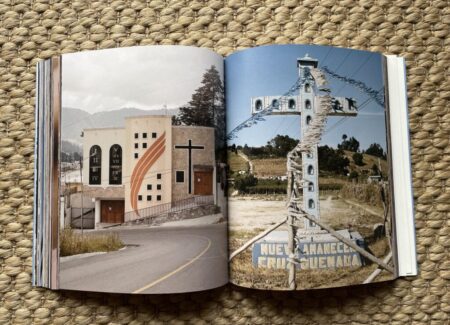

Genesis is divided into five sections or chapters (separated by single black pages), each with its own subject matter. The first chapter provides an introduction of sorts, capturing the diverse rhythms of daily life in the region. From the start, Brenner offers contrasts: between a Catholic first communion and an evangelical Christian mega-church; between traditional weaving work on a loom and a party live streamed to Guatemalan immigrants working in the US; and between older men in cowboy workwear and younger men in baseball hats and Wu-Tang Clan t-shirts. And it is these details that Brenner notices that allude to the hybridizations taking place: the traditional tattoos, the ancient ruins, the roving music bands, the old school bare-knuckle fights, and the pre-Colombian “flying pole” ritual, as well as the pickup trucks, the smartphones, the high heeled shoes, and the narco jewelry, all mixed together.

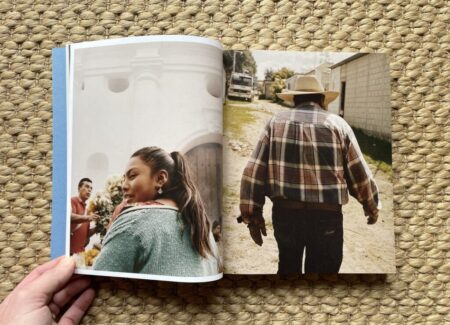

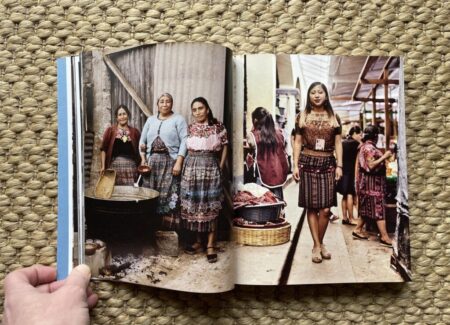

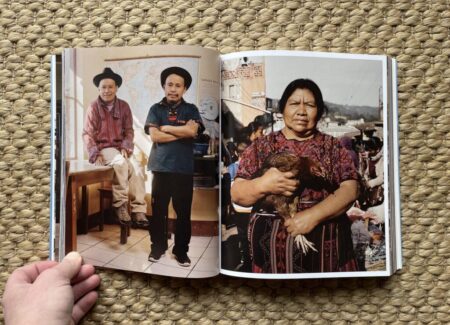

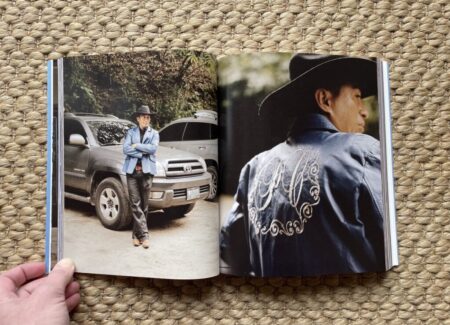

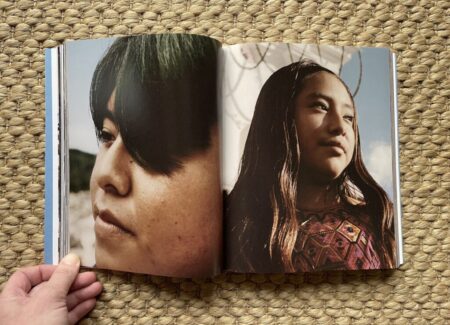

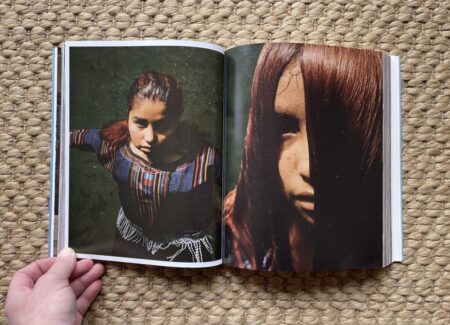

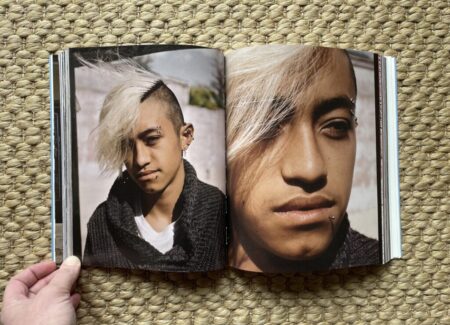

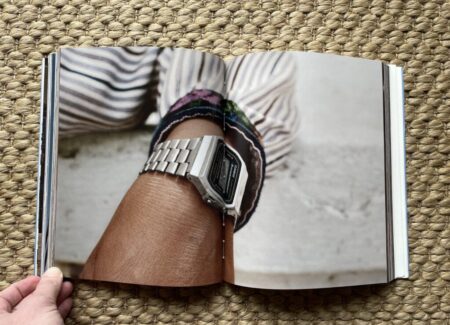

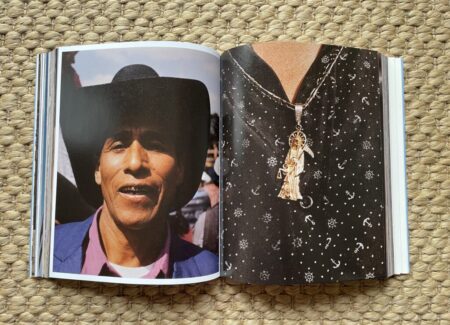

Even though Brenner was an outsider to the Highlands, he seems to have invested real effort in interacting with all kinds of people, with some actually inviting him into their homes for more intimate interactions and portraits. The second chapter of Genesis is entirely filled with images of people, in a number of cases, seen in paired portraits (across a single spread) of the same sitter. The contrasts between young and old – in terms of fashions, styling, and symbols of wealth and status – are clear. For the older generation, intricately hand woven fabrics with rich color detail are status signifiers for the women (as well as the ability to purchase the largest hen in the market), while cowboy hats, embroidered shirts, leather vests, suit coats, “power sticks”, and SUVs provide the same function for the men. But the young people have largely moved away from these styles, or hybridized them with fresher fashion accessories – football hoodies and soccer jerseys, designer and pop culture brands, and prominent smartphones are often matched by dyed hair, long fingernails, watches, and handbags, even when traditional attire provides a baseline. When old and young are intermingled together in Brenner’s flow of faces, the churning mix of evolving styles and intentions becomes much more visible.

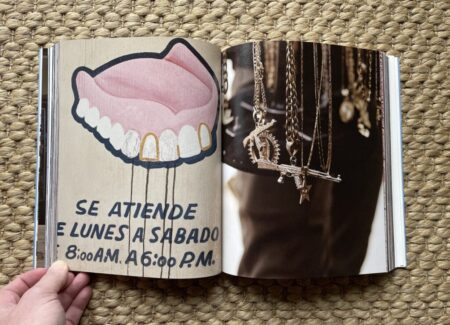

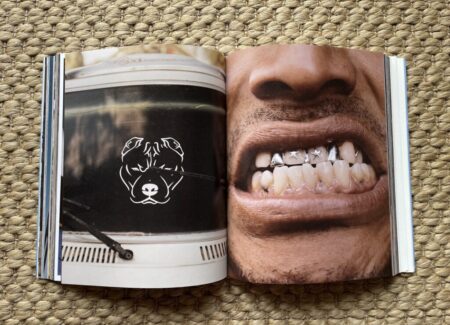

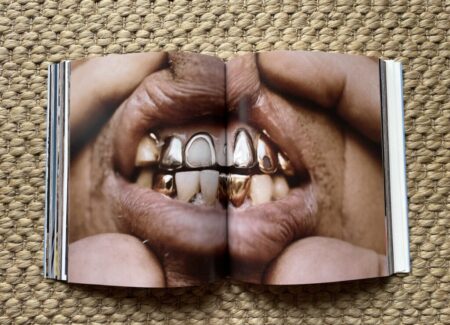

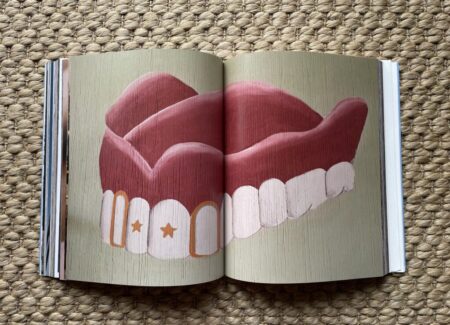

Chapter three is a deliberately unruly parade of bling, which Brenner sees as a resonant symbol of what’s been happening in the Highlands. Historically, personal decoration with gold and precious stones reaches all the way back to the Mayans, and the extraction of gold was a primary objective of the Spanish colonists. Brenner connects those impulses to the contemporary trends of putting gold in the mouths of Guatemalans, as “grills” and other adornments, and of the wearing stacked gold necklaces, pendants, bracelets, and belt buckles like popular hip-hop and reggaeton artists, by young and old alike. His photographic approaches to documenting this theme include close-ups portraits of smiling mouths and faces, pictures of dental molds, and images of painted murals, sandwich boards, and displays used by dentists and “dental technicians” to advertise their labs and services. The resulting chapter is an extended parade of teeth decorated with shiny golden edges, stars, letters, and other symbols, blending traditional local craftsmanship with aspirational material power and wealth.

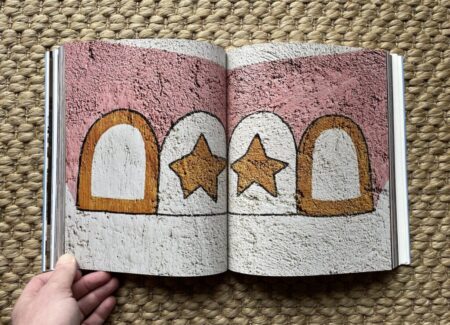

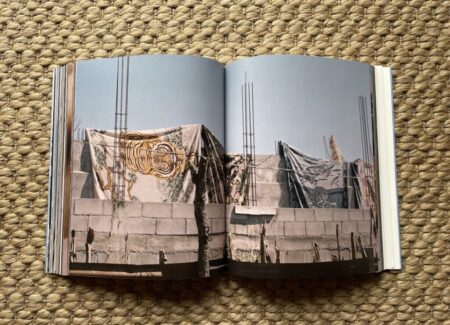

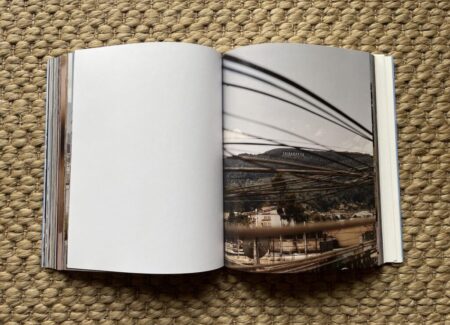

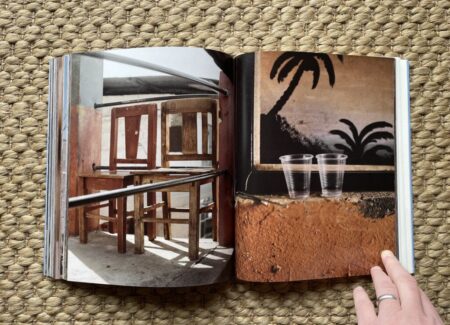

The last two chapters step back from human subjects and look more closely at the built environment in the Highlands and the smaller details Brenner has discovered along the way. An earthquake in 1976 demolished many buildings in the Highlands, and in the years since, a new hybrid architecture has begun to emerge from that wreckage, combining traditional aesthetics with more contemporary building practices. Brenner’s photographs scan the land, documenting houses, hotels, churches, and other in-process construction projects. And while he is clearly interested in the emerging forms of these structures, his eye in not without criticism of its sprawl, its ugliness, and its encroaching damage to the environment – the “paradox of progress” is repeatedly seen in eroded hillsides, ostentatious narco-architecture, and electric wires that criss cross in front of wide vistas.

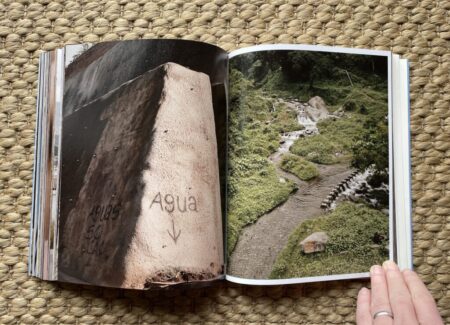

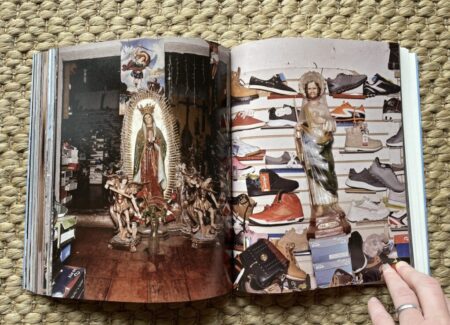

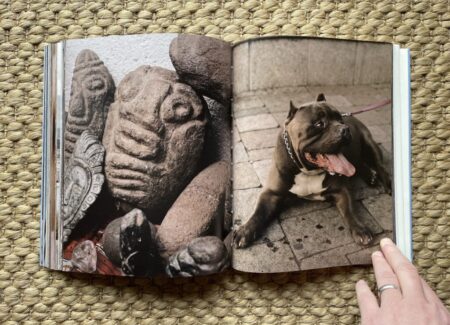

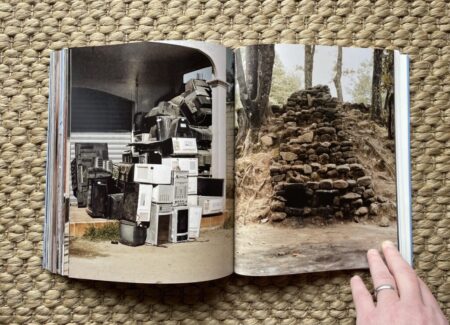

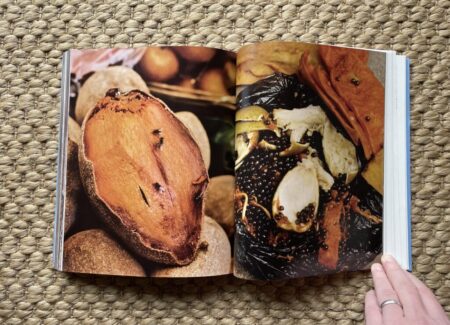

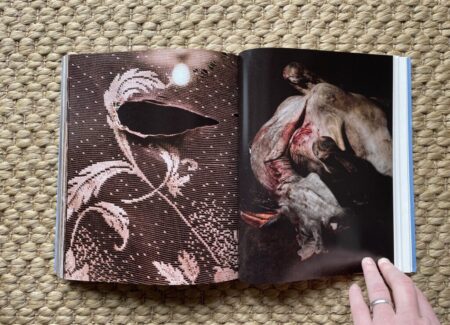

The last section once again blends old and new, taking note of the friction found in a Saint Jude statue nestled in among a sneaker display. Long standing traditions are very much in evidence – in foods and dishes, in local fruits, in zoomorphic rocks and piles of stones, in holy sites and religious practices, in horses, in stray dogs lying in the sun, and even in the sacrifice of a chicken. Brenner then upends these rhythms with images of car hood ornaments, exotic birds, cartoon characters, a jumbled pile of electronics and computers, a lottery kiosk, and a stack of new plastic wrapped coffins. The book ends on an ominous note, in the pairing of a tear in a traditional fabric and the bloody slaughter of a cow.

In the included interview, Brenner alludes to Guatemala’s cell phone penetration, which is the second most per capita in Latin America. He sees this technology-driven connectedness to the global community creating many of the changes visible in the Highlands, in fashions, in attitudes, in politcal beliefs, in personal expression, and in the ways traditions are being adapted to the new age. Genesis is Brenner’s attempt to get his photographic arms around these forces, and when seen as a single integrated art object, it is surprisingly successful at finding the pressure points in the ongoing transition. His observational archive is full of shared energy and vitality, but it isn’t without attention to more painful realities and uncertain futures. It is this tension that gives Genesis its durable spark, even if we might see it a decade or two from now like a time capsule.

Collector’s POV: Juan Brenner is represented by Rocket Science Studio for commissioned work (here), but does not appear to have consistent gallery representation for his personal work. As a result, interested collectors should likely connect directly with the artist via his website (linked in the sidebar).

https://www.tobegallery.hu/genesis

https://www.tobegallery.hu/paris-photo-5

https://www.tobegallery.hu/unseen-amsterdam-2