JTF (just the facts): A total of 11 color photographs (7 displayed individually, 4 as two pairs of diptychs) that are framed (in hues that range from blue to brown) on four white walls in the main room of the gallery. All are archival pigment prints and dated 2018. Two of the prints are creased and unique; the others are in editions of 3 with 2AP. Sizes vary from 32 5/8 x 26 ¾ inches (the diptychs) to 53 ¾ x 42 ¾ inches. Two are horizontal; the others are vertical. (Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: John Houck’s Portrait Landscape (2015), in which he applied facial recognition software to video stills from the film Blow-Up, is one of the essential art works of this decade. Wickedly funny, a logical mash-up that addresses our anxieties in the Age of Terrorism and questions our blind faith in technology to protect us, it reached into the pop culture past to talk about the Orwellian future. The computer program does as instructed with this movie artifact, obediently searching for human features among patches of leaves in bushes and trees of the park, where actor David Heming in the movie may have witnessed a murder with his camera. While the piece reiterates what Antonioni had suggested—that photographic images are deceptive indicators of truth—Houck also layers this familiar message with a sly reference to the history of video games. The cursors in Portrait Landscape that dumbly move from side-to-side around the screen, searching in vain for hidden faces, are as sophisticated as the bars and balls in that most primitive of electronic toys, the 1972 arcade hit “Pong.”

Why the artist hasn’t ventured more frequently into this more satiric realm, where his computer skills might unpack buried fears about technology run amok in the contemporary world, is a mystery.

In this exhibition at Boesky of 11 prints made in 2018, he once again uses software programs to make still-life collages full of trapdoors designed to frustrate the viewer who wants clean distinctions between reality and invention, photography and painting—conceptual territory he has explored since at least 2012.

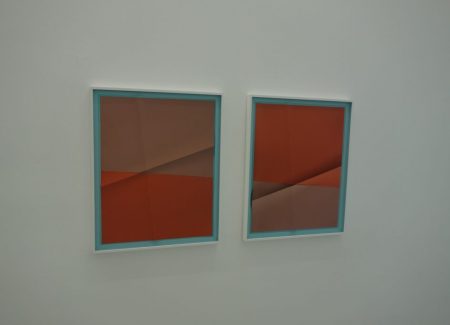

Accumulator #20, 3 Colors #B2DAE5, #B4867B, #B46E5C is a diptych done in two digital shades of peach. The divisions between light and dark on the left-hand print are about equal, while in the right-hand print dark occupies more space, is on top, and seems to press down on light. Each print has an actual crease in the paper as well as virtual ones. The two actual creases are at a similar diagonal on the two sheets but one is slightly higher than the other; while the virtual creases seem to connect across the two prints, the line from one extending to the other. A pale blue border outlines both rectangles.

Delicate abstractions, with a physical presence as well as a ghostly one, they are like close-ups of Japanese wrapping paper or perhaps an early work by Dorothea Rockburne. Accumulator #21, 3 Colors #829AA8, #8F6B69, #007D98 repeats this virtuoso exercise in blue and brown.

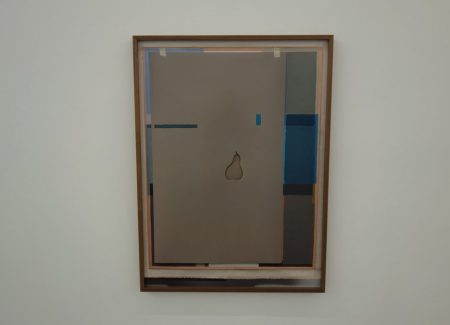

Other works invoke the tradition of craft more openly. Rejoin places two pairs of hands and forearms at the center, fingers touching as if captured while making or repairing something. The patchy tones on the flesh and sleeves, and a stack of three small paint cans, are done in post-Impressionist style, and in some places with actual paint. A cut-out of a pear in Notes on a Briefcase and the parti-colored mountain (frame of a window or a painting?) in Presenting the Past are salute the motifs and brushwork of Cézanne.

Much of Houck’s work moves aggressively into the digital world of unbounded image-making without wanting to let go of the past, which he folds, refolds, doubles, and reframes within multiple layers. He is too young to accept the old dispensation that puts a premium on the knock-out single photograph. His hope seems to be that rephotographing might more accurately reflect the recursive process of memory and provide him access to an inner life that he could put on paper.

The title of the show is taken from the writing of the English psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott, one of the founders of object relations theory. A “holding environment,” in his terminology, is the ideal of a nurturing or supportive network that a therapist creates for a patient or a parent for a child. Houck has himself lately begun psychotherapy and is a new dad. While preparing this work, he had moved back to his childhood home in Portland, Oregon.

Unstable Figure is a product of this return to his family’s nest. On a series of interlocking rectangles in pale shades of gray and brown, Houck has drawn/photographed two pairs of hands and forearms gripping two racing bike handlebars. One set of arms belongs to an invisible body headed to the left; the other set is oriented down and to the right. Stripped of their brakes, the handlebars curve at their ends like the horns of a bull, semi-circles that lyricize the rigidity of the squares. According to the press release, the image is meant to summon up youthful memories of time spent on bicycles with his father.

More than ever, Houck is taking his cues from the history of painting rather than photography. The models for these hermetic still-lifes may be the post-1980s collages of Jasper Johns—works like Summer or Spiral Galaxies, which are riddled with personal clues that only the artist is equipped to decipher.

A careful distiller of tradition and his own place within it, Houck takes his time in putting elements together. He makes and exhibits his fastidious prints in small batches. As an undergraduate in architecture, he learned to design his own software and manipulate space on a screen. He’s an artist totally fluent in the language of the digital nether regions and has no qualms about painting on photographs, concocting images that mimic oil or acrylic, or letting the computer devise its own colors and textures algorithmically.

How much longer will Houck continue to tunnel inward? These new works, like many of his previous ones, are primarily concerned with the intricate processes of their own creation. Will he remain inside the comforts of the digital bubble and ignore real-world issues that could threaten the future of his new child? I look forward to the day when he again finds potent material, as he did in Portrait Landscape, that’s a suitable match for his formidable intelligence.

Collector’s POV: The works in this show range in price from $16000 to 24000, based on size. Houck’s work has little secondary market history at this point, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.