JTF (just the facts): A total of 26 color photographs, either framed in silver or unframed and pinned directly to the wall, hung against while walls in the two room gallery space, the entry area, and the nearby office. All of the works are archival pigment prints, either on photo rag paper or canvas, made between 2012 and 2019. The works on paper range in size from 16×18 to 34×34 inches (in editions of 6), and the works on canvas range in size from 24×95 to 36×150 inches (in editions of 3). The show also includes an installation of 18 digital prints on taffeta (measuring 10x12x10 feet) from 2017. (Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: If there is any one agricultural crop that is most associated with the history of slavery in the United States, it is cotton. Cotton was a massive cash crop in the 19th century South, and the specifics of the plant itself (and the lack of efficient mechanical harvesting at the time) necessitated the use of a large labor force. Because cotton starts to deteriorate right after it blossoms, it had to be harvested quickly, with multiple passes through every field to compensate for different maturing times. Hot sun, heavy loads, and long work days were the norm, and if these weren’t enough, the thorny plants required careful hand picking, the sharp edges and spikes bloodying the hands of the workers. So slave labor was used to bring the crop in, ultimately turning cotton into a powerful symbol of the systematic exploitation of African-Americans.

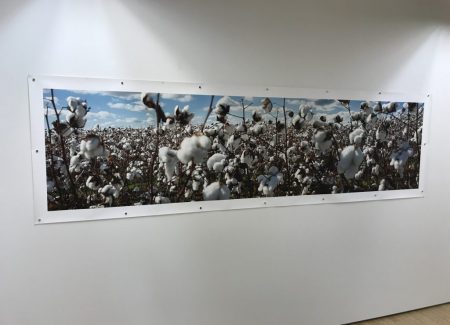

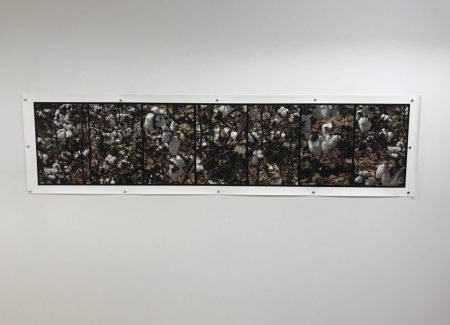

John Dowell’s recent photographs use cotton as a consistent visual theme, turning wide views of fields of puffy white plants and the up close isolation of specimen details into reusable motifs he can digitally redeploy in more complex excavations of history. In one group of images, he keys in on the enveloping physicality of cotton, pulling us down into the dense thicket of branches, encouraging us to feel the dust and the thorns, and to peer up through the blossoms into the wide skies above. As panoramas, these photographs stretch to fill entire walls, making their presence that much more overwhelming, a twilight view of the endless fields dappled with white seemingly uniform for as far as the eye can see. Dowell then moves beyond the literal to imagine cotton balls (and the misty pink light of those long departed) floating in the skies like angels, and to add the graphic wordplay of “When I See Cotton, I See Red” across a wide field of plants, doubling red into associations of both blood and anger.

An installation of hanging panels in the center of the gallery amplifies this sense of physicality even further. Inspired by his grandmother’s story of getting lost in the cotton fields as a young girl, Dowell’s claustrophobic installation allows us to walk inside an approximation of tightly nested cotton rows, and to get turned around and disoriented by the plants that rise above our heads. The telescoping arrangement of the panels forces us to brush up against their edges, mimicking the feeling of the plants scratching us as we pass through. “Lost in Cotton” is a resonant work, one that makes us feel the very human sensations of being overwhelmed by cotton, thereby making the larger implications of the plant and its dark history in America all the more personal.

Dowell then moves on to more fantastical re-imaginings, excavating New York city history using cotton as a visual metaphor for black lives erased. A group of images start with bucolic contemporary views of Central Park, which are then digitally altered to include hand scratched houses and churches (some with slashing flames erupting from the windows and chimneys), ghost images of former inhabitants, and seas of enveloping cotton, these eerie manipulations co-existing with the modern day dog walkers and footpaths. The scenes recreate places in the former Seneca Village, a 19th century middle-class African-American community that was seized (via eminent domain) and then razed to build the park. Dowell’s images seem to actively oscillate between past and present, with the rhythms (and horrors) of the past no longer entirely invisible.

He uses a similar approach in images of Wall Street, bringing the former municipal slave market (the second largest in the country in the early 1700s) that was located there back into clearer view. Cotton tumbles from between the massive stone pillars that now hold up condominiums, and cotton fills the urban canyon all the way to Cipriani, the wealth made from the slave labor that picked the crop and the wealth still centered in this neighborhood today uncomfortably intermingled. Dowell also travels up to Harlem, where a statue of Adam Clayton Powell seems to triumphantly rise up out of the cotton.

While Dowell’s images aren’t as personally traumatic as Nona Faustine’s portraits at similar New York locations or as symbolically taut as Hank Willis Thomas’s “The Cotton Bowl” (from 2011, where a black cotton picker faces off with a black football player), his works aim for and successfully interrogate similar psychological terrain. They smartly use the simple dots of white cotton to force us to remember truths that have largely been forgotten, his images encouraging the ongoing process of collapsing, reassessing, and rebalancing our collective history.

Collector’s POV: The works in this show are priced as follows. The photographs on paper are priced between $2700 and $5700 each, while the prints on canvas range between $9000 and $16000. The installation is priced at $45000. Dowell’s work has little secondary market history at this point, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.