JTF (just the facts): A total of 20 black and white and color photographs, framed in white and alternately unmatted/matted, and hung against white walls in the main gallery space and the smaller side room.

The following works are included in thew show:

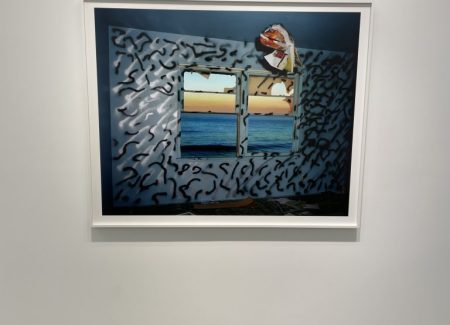

- From the Zuma series: 8 archival pigment prints, 1977/early 2000s, 1978/early 2000s, each sized roughly 44×54 inches, in editions of 3

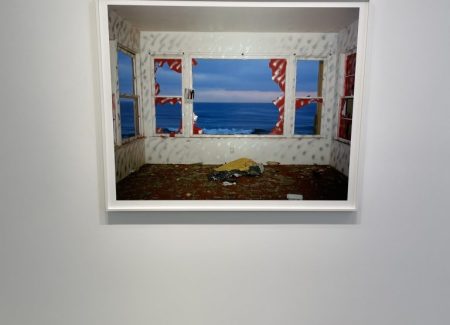

- From the Daybreak series: 12 gelatin silver contact prints on Azo paper, made between 2015 and 2020, each sized roughly 14×17 inches, in editions of 5

(Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: Yancey Richardson’s new show of the work of John Divola follows an altogether predictable model. Pairing a new body of work with an older classic, especially if there is some subject matter affinity between the two projects, can offer the possibility of clear visual contrasts, parallels across time, and even evidence of evolution in thinking or aesthetics. It also provides the opportunity to lure visitors in with something well-established and familiar, and then to pivot them toward the related aspects of the more recent pictures, thereby providing some relevant historical context for what is artistically taking place now.

Divola’s Zuma series hardly needs any introduction – it’s a cornerstone classic of 1970s American color photography. Made in 1977-1978, in an abandoned house on Zuma Beach in southern California often used for fire department training exercises, the photographs offered a bold break from the traditions of landscape photography. Using the charred, broken windows of the house to frame the changing seascapes outside, and over time, making his own physical interventions in the space (particularly with patterns of spray paint), the resulting images featured not only brash eye-popping color, but a more incisively conceptual perspective on both the saccharine grandeur of an orange sunset and the decaying America of that moment in time.

The first prints Divola made of the Zuma images were relatively small chromogenic prints, roughly 10×12 inches in size. These were followed a few years later by a dye transfer portfolio, in a slightly larger size (14×17 inches) and in a larger edition (30). As the years passed, some the chromogenic prints started to fade (as they apt to do), and Divola replaced a few with pigment prints from an edition released in 2003, again slightly larger (24×30 inches).

The reason for this quick interlude into the details of the various Zuma prints over the years is that the pigment prints on view in this show are the largest in the progression, roughly 44×54 inches in size, rivaling the 44×60 inch pigment prints that William Eggleston made of some of his most famous images in 2012 (Eggleston’s prints were sold at Christie’s, previewed here, with results here). As with Eggleston’s prints, when a photographer reissues iconic work in significantly larger sizes, there is a certain amount of potential skepticism to overcome, not just from holders of earlier, smaller, vintage prints, but from those who might feel like the prints are simply an effort to essentially sell again what has already been sold, albeit at higher prices.

While bigger is by no means better in all cases, these muscular wall-filling modern Zuma prints feel well matched to the original compositions, and in many ways, the additional scale feels like a natural fit for the spaces (and the see-through effects) Divola was photographing nearly 50 years ago. Not only do the larger prints mimic the scale of the windows they document, there is a sense of walking into these very rooms, of being present inside the images, that is different than when the prints were much smaller – we can now inhabit Divola’s altered rooms, rather than peer into them like jewel boxes.

At this scale, the saturated colors, of course, jump off the wall. But more intriguing in this larger world is the sense of geometric order in the management of the exterior seascapes and their varying horizons in relation to the framing of the windows; the views feel less like decorative afterthoughts and more like integrated motifs that have been flattened by the camera into the same plane as the foreground architectural structures. I felt this internal/external tussle in Zuma much more strongly than ever before in these big prints. When small, we were encouraged to place our attention on the expressive interventions inside the prints, and to examine closely the broken glass, the charred wood, and the splashes of paint that swirl around on the walls and ceilings; when larger, the space appears to fill out, pulling us into the rooms with more physicality. This is especially true in the views that are more squared off and frontal, as we seem to peer directly from the gallery space, through the rubble, and out to the sea in one sweep of vision; in one famous work, Divola has tossed a magazine into the air in front of a classic blue sea orange sky sunset, and in the large print, that unexpected flying intervention feels disruptively right nearby.

If the plan for this show was to use these large scale Zuma prints as a lead in for Divola’s new work, that strategy seems to have been somewhat misguided, in several ways. First, the intense visual stimuli of the Zuma pictures overwhelms (in a good way) everything else nearby, including Divola’s more subtle black and white photographs in the side room. And second, Divola’s new works were already shown in New York in another gallery show just a few months ago, paired with prints by Frederick Sommer (reviewed here), so their presentation here isn’t quite the reveal that it might have been. Such a scheduling double up certainly feels mismanaged, and meaningfully lessens the potential impact of the new works as shown here, even if the audiences of the two galleries don’t entirely overlap.

That’s too bad, as there are plenty of nuances worth discovering in the Daybreak series. Divola made the images at the decommissioned George Air Force Base, in Victorville, California, over the hills east of Los Angeles, and there he followed his well worn script of making interventions in the junked rooms. Unlike the Zuma photographs though, the Daybreak pictures hardly ever look out from inside; instead, they stay claustrophobically centered on the wall facing the camera, with few if any windows to break up the quiet gloom of the early morning. The mood is reserved and introspective, as the soft light leaks in, sometimes dappling the walls and floor from holes in the ceiling, at other times burnishing the walls with a subtle glow. Divola experiments with many motifs he has used before (spray painted starbursts and splashed dot patterns, dark orbs that hover like portals through time), and adds new efforts with draped cut paper, that alternately layer into overlapped billows, pile up into cave-like openings, and are cut away revealing empty blackness.

What feels particularly different about the Daybreak pictures is that they feel rooted in accumulation and aggregation – not just Divola and his improvisational interventions, but the layering together of everything else that has come before in these rooms. Divola is just the most recent occupant, and his gestures lay atop other choices and decisions by previous inhabitants; new marks interact with old ones, and dirt, rubble, and decay add texture to rooms that Divola has recently transformed. This gives the resulting photographs richness and uncertainty, in ways that are less direct (and much more understated) than in Zuma.

As an integrated experience, somehow this show feels inverted. It’s almost certainly easier to sell the colorful big prints from Zuma, and they are undeniably engaging, but from the perspective of continuing to build Divola’s career, perhaps these two bodies of work needed to be reversed, with the Daybreak pictures given a more prominent and full chance to tell their own story. As seen here, they feel overshadowed, or an afterthought, with less commitment behind them than there might have been. From my vantage point, this short term hedging does a longer term disservice, especially with an established artist like Divola, where a show of new work is an important marker in a methodical progression. Of course, we admire the Zuma pictures – they’re acknowledged icons at this point; what we need to be taught is that the Daybreak pictures also have something exciting to show us – about Divola, about his continued development as a photographer, and about the ever evolving possibilities of the medium.

Collector’s POV: The prints in this show are priced as follows. The Zuma prints are $19000 each ($24000 for the AP), while the Daybreak prints are $6500 each. Divola’s work has only been intermittently available at auction in recent years, with prices generally ranging between $1000 and $22000.