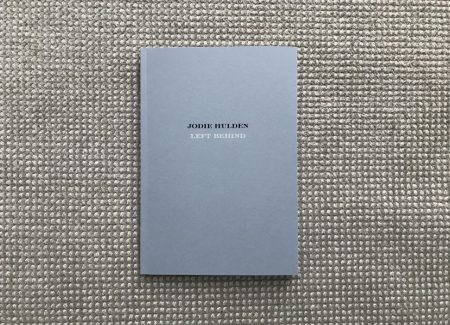

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2019 by Dark Spring Press (here). Softcover, 6×8.75 inches, 64 pages, with 29 color reproductions. Includes essays by George DeWolfe and the artist. In an edition of 120 copies, 30 of which are Collectors Editions (with a signed print). (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: The town of Bodie, California, sits southeast of Lake Tahoe, east of the Sierra Nevada mountains near the Nevada border. In the 1870s, Bodie was a gold rush town, swelling to nearly 8000 inhabitants when the mines were running. But just a few decades later, the boom cycle had turned to bust, and the town emptied out. By 1915, it was officially a ghost town, with a grand total of zero residents.

When the tide turned on Bodie, and new strikes elsewhere caught the attention of its get rich quick prospectors and hangers on, the people didn’t stop to carefully pack up their things – they just took off, essentially leaving everything behind. With its isolated location, the dry climate, and the connecting rail line closed, Bodie has stayed remarkably well preserved in the years since (becoming a state park in the 1960s). Like Pripyat, Ukraine, after the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, it now has a feeling of eerie emptiness, its once active life seemingly erased in an instant.

Making photographs in such a place offers a number of artistic and aesthetic traps. There’s the Old West trap of cowboy town clichés – the gunslingers and sheriffs, the saloons, the ten gallon hats, and the dusty streets. And there’s the newer trap of ruins seen without context, where the textural beauty of decay is isolated from a sense of human impact, as has often been the case in images of early 2000s Detroit or pastel-hued Cuba. Both approaches turn a town like Bodie into a stage set, without actually seeing it.

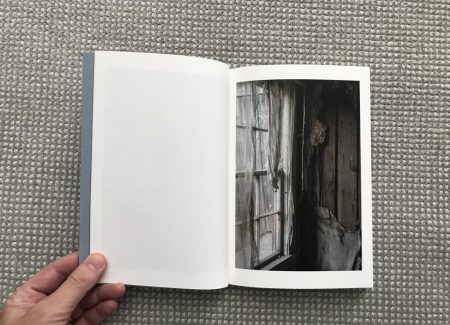

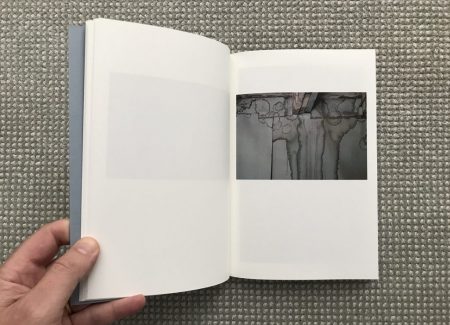

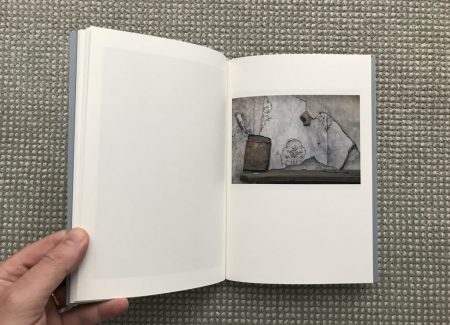

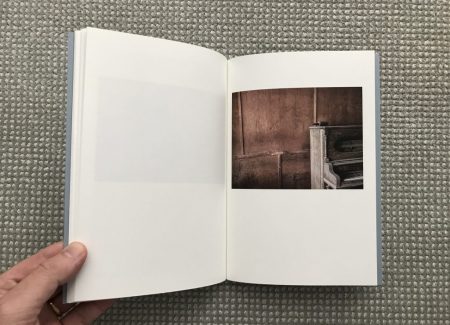

The photographs of Bodie in Jodie Hulden’s photobook Left Behind skirt these danger zones, and largely avoid them. Her images do show us an old broken-keyed saloon piano topped by a beer bottle and a crusty shoe shine chair, and revel in the surfaces of peeling wallpaper, worn floor boards, and creeping stains, but her observations step beyond the obvious. She is understated and respectful in her wanderings through the vacant buildings, and she is often drawn in by the patina of human touch or absent presence, which gives her photographs a sense of quiet intimacy.

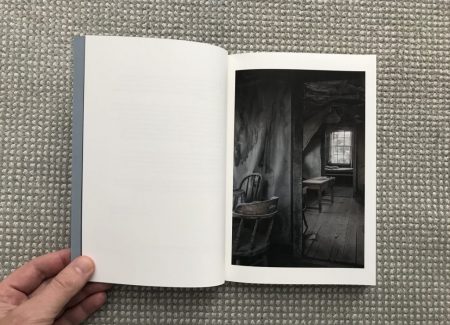

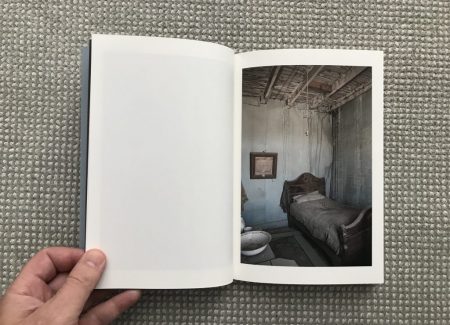

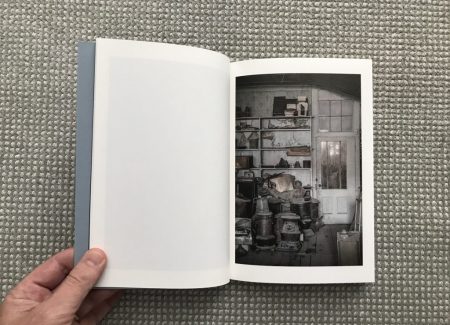

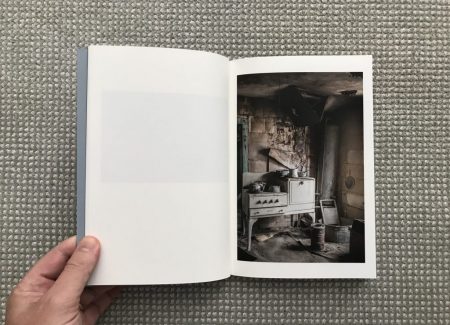

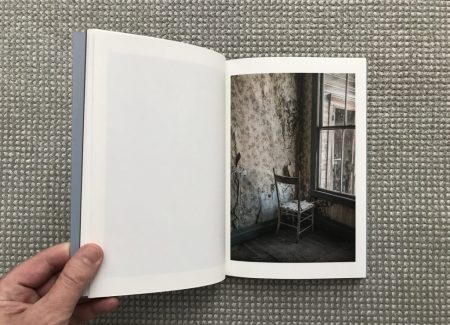

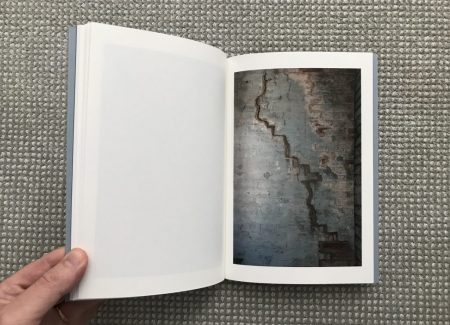

Like Walker Evans’ images of the sparse furnishings in the homes of Alabama sharecroppers, Hulden’s pictures often show us a view into a cramped room, where a few anonymous possessions provide all of the functional decoration. The walls, doorframes, floors, and ceilings themselves provide much of the visual interest, the aging textures of rough hewn planks, floral wallpapers, painted bricks, and wood paneling offering clues to forgotten histories. Hulden then shows us a stovetop, wood stoves, kitchen shelving, tin washboards and buckets, and other everyday furnishings that help us connect to the rhythms of life at that time.

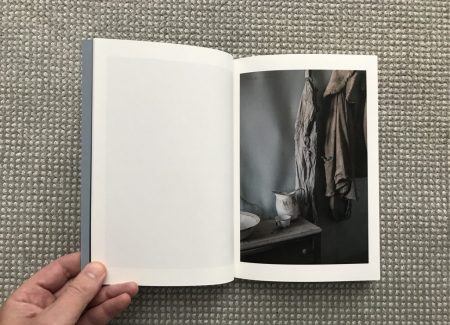

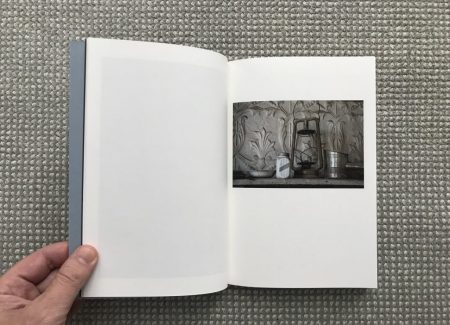

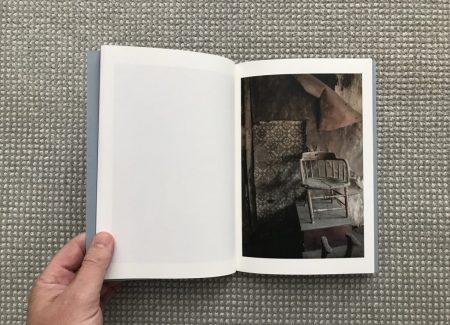

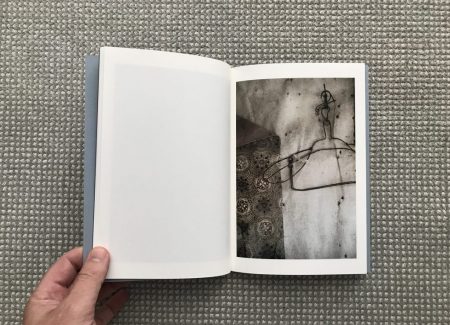

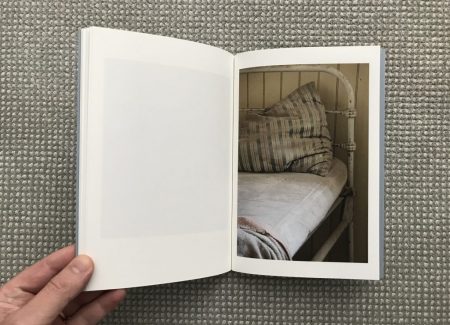

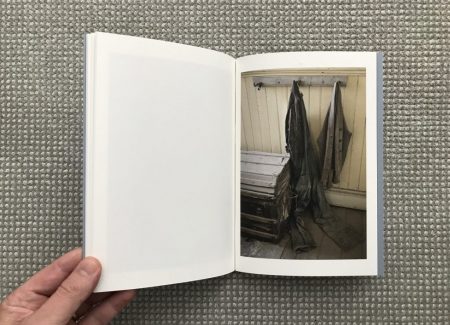

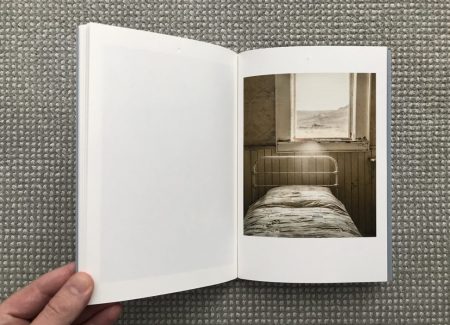

Many of Hulden’s strongest photographs move in even closer, using something more personal to anchor her compositions. She notices chipped iron bed frames, sagging pillows, and the ceramic coated washbasin and pitcher on a dressing table. She isolates dusty eyeglasses, rotting papers and books, a lantern, a metal hanger, a single shoe under the bed, a chair with painted decoration, and a wooden trunk, each seemingly inhabited by ghosts. And these spectral connections get stronger when she discovers old clothing, the worn overalls, tattered coats, limp sweaters, and even a uniform with brass buttons seeming to recall the stories of their past owners.

Hulden’s color photographs employ a deliberately desaturated palette, where the greys, browns, blues, and whites feel softened and faded. Natural light fills the images, streaming in through paned windows and doors framed by gauzy rotting curtains. Like Andrew Wyeth’s New England interiors, there is a muted tenderness to Hulden’s rooms, where melancholy lingers in the air. A few pictures edge a little too close to preciousness, but most successfully reach for the intimacies that can be unlocked by the attentive observation of textures.

Left Behind bears all the hallmarks of thoughtful, unpretentious design. It’s a relatively small photobook that fits snugly in your hands, and the paper stocks are richly tactile. The images are placed one to a spread, always on the right side, so the pacing of the page turns is slow and deliberate, encouraging the viewer to look closely at the details Hulden has captured. And short essays bookend the pictures to provide some context and background. Seen as an object, it’s a well crafted package that smartly matches the aesthetics of the photographs.

What makes this project work is that while the colors and surfaces in Hulden’s photographs are often lovely, she doesn’t let them be the end point of her visual journey. The silent emptiness of Bodie, and its faint echoes, pull us in, opening up human histories that still resonate across time. The dust has long since settled and the air has grown stale and musty, but as seen by Hulden, the discarded artifacts of gold rush life still have a tingle of human connection.

Collector’s POV: Jodie Hulden does not appear to have consistent gallery representation at this time, As a result, interested collectors should likely follow up directly with the artist via her website (linked in the sidebar).