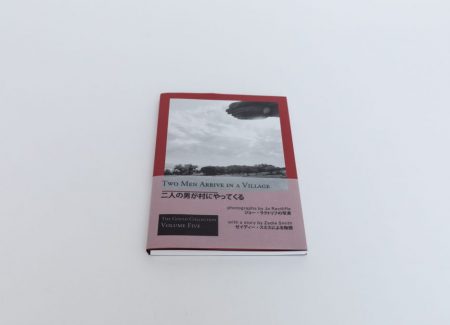

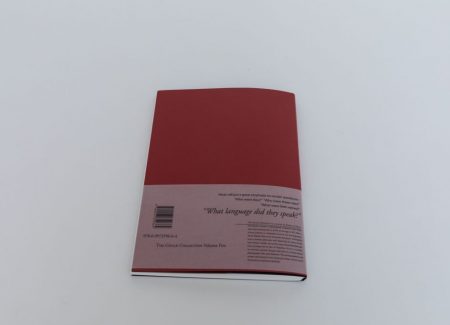

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2021 by The Gould Collection (here). Softcover (9.75 x 7 inches) with exposed Swiss binding in dust jacket and belly band, 92 pages, with 49 black and white photographs. Includes a short story by Zadie Smith. Edited by Laurence Vecten, Russet Lederman, and Yoko Sawada. In an edition of 800 copies. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Two Men Arrive in a Village is the fifth volume published by The Gould Collection in its series of books pairing short stories and photography. The collection was started to honor the memory of the photobook collector Christophe Crison who passed away tragically in July 2015. The name of the series comes from the pseudonym Crison used online, Gould Bookbinder, the protagonist of Stephen Dixon’s novels (one of Dixon’s short stories appears in the first volume paired with images by Mikiko Hara). The series was started by three women, Laurence Vecten, Russet Lederman, and Yoko Sawada, based on three continents, and offers a sophisticated exercise in collaboration, trust, and creativity.

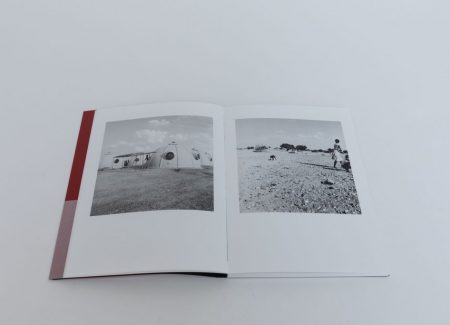

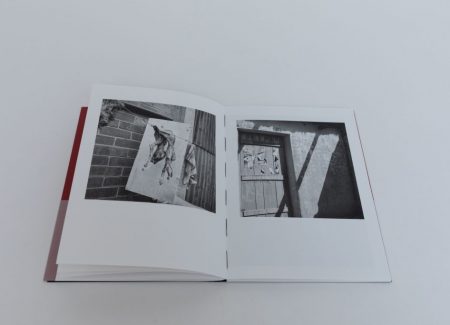

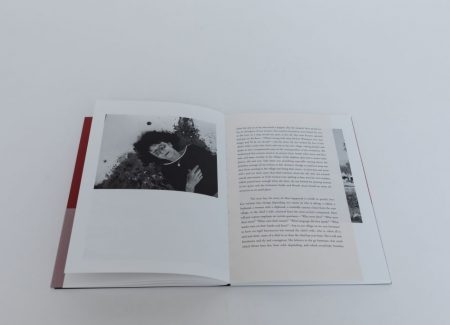

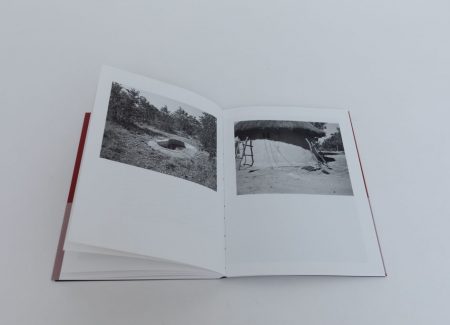

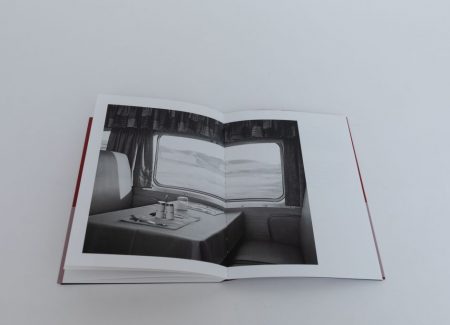

Working on this series, the editors first agree on a photographer they would like to invite, and then go over various short stories to find the best fit, now in close discussion with the photographer. All of the books in the series have the same size, and with occasional deviations, follow a similar design. In this case, Two Men Arrive in a Village is a softcover book with a dust jacket, and a belly band includes the name of the artists in both English and Japanese. An exposed spine is a nice design element. All of the photographs are gorgeously printed in black and white, slightly varying in their sizes and placement on the pages, creating a more dynamic visual narrative. The pages with the text are slightly narrower, adding curious overlaps with nearby images and emphasizing the connection between them. The title of the book is borrowed from the included short story.

Two Men Arrive in a Village creates a conversation between photographs by the South African photographer Jo Ractliffe and an allegorical short story by Zadie Smith (originally published in 2016). Both artists offer commentary on violent legacies, destruction, and the imbalances of power, and do so using imagination and allegories. Ractliffe is one of the most influential social documentary photographers in Africa. Throughout her career, she has focused her attention on landscapes, examining themes of conflict, displacement, and absence. Her photographs deal with the violent legacies of apartheid and its aftermath, reflecting on South African history and memory.

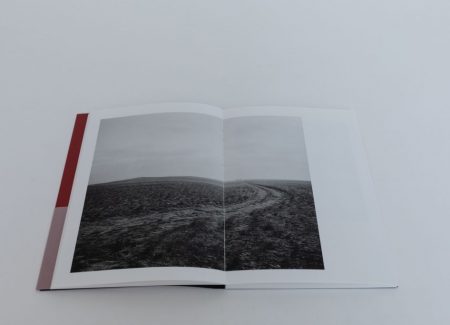

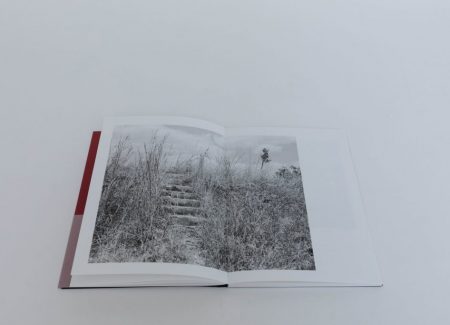

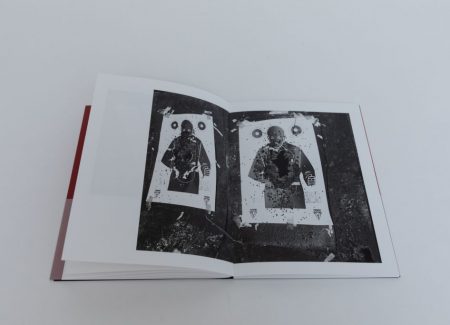

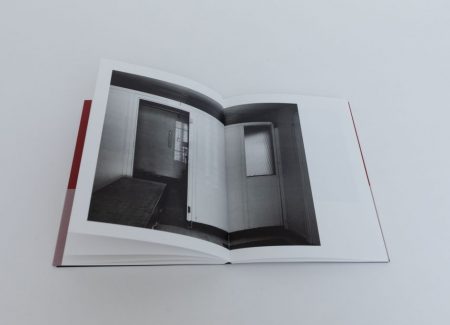

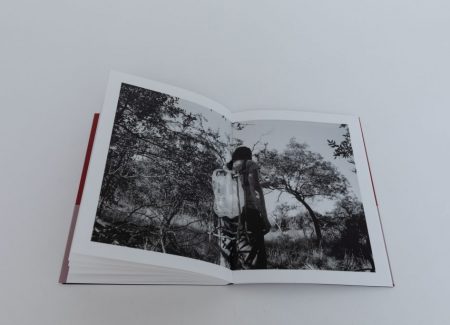

Ractliffe’s black and white images selected for this book were made in the past four decades, basically drawn from her entire body of work, in various locations in Africa. In the mid 1980s, she photographed townships of Cape Town, and she later extended her concern beyond South Africa, going to Angola to document the aftermath of the Angolan Civil War (1975-2002) and looking at the traces of the intertwined conflict known in South Africa as the Border War (1966-1989). Her photographs are often silent and desolate, primarily using landscape or space to expose the consequences and effects of events that took place in the past. Her attention to small and at first unassuming details present in the landscape connects the present and the past, exposing the unsettling truths of war.

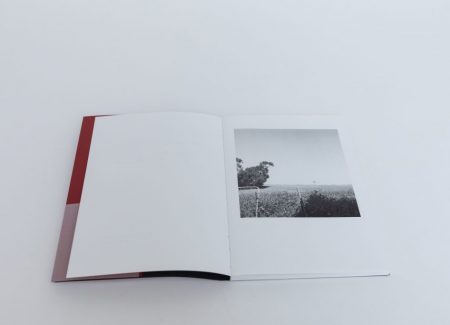

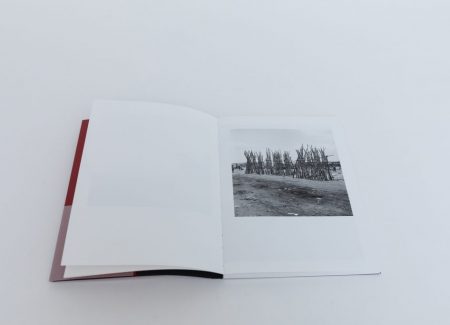

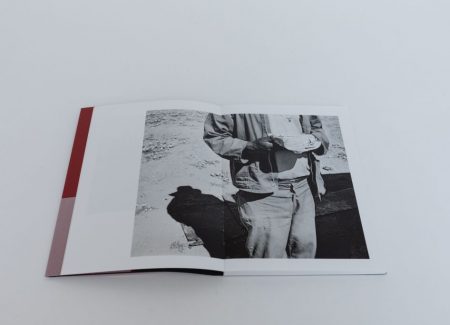

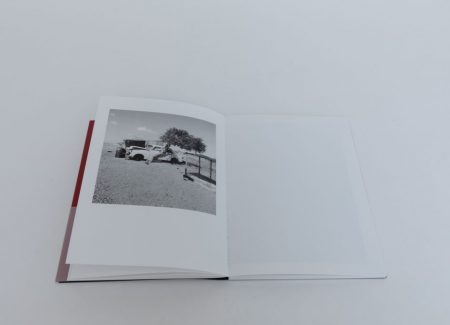

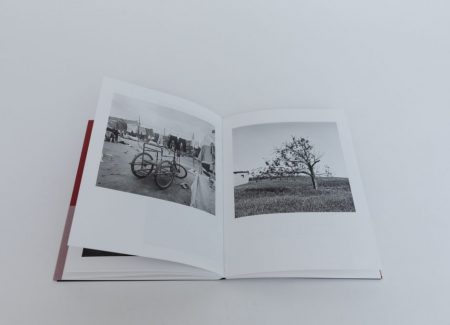

A calm square photograph of a wheat field opens the book, orienting us to its details, such as parts of a fence, an old windmill, and wheat leaves. The images in the first few pages show a market behind a wooden structure, a man outside holding a worn book, the façade of a building, a rocky desolate landscape with people appearing as small figures, and an old car left between a shack and a crooked tree. Many of them are quietly formal and sparse. These images set the tone for the narrative, building tension and encouraging us to consider untold stories. Ractliffe’s photographs are often open-ended, allowing the viewer to fill in the blanks.

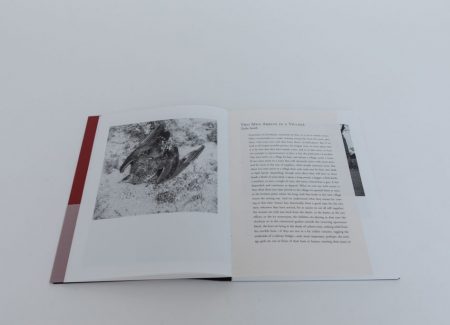

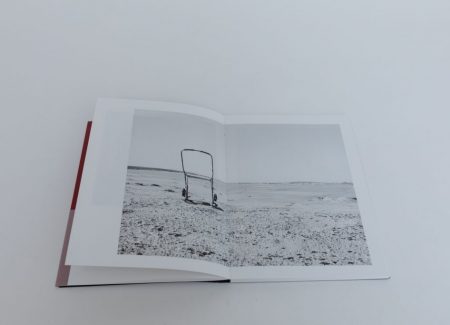

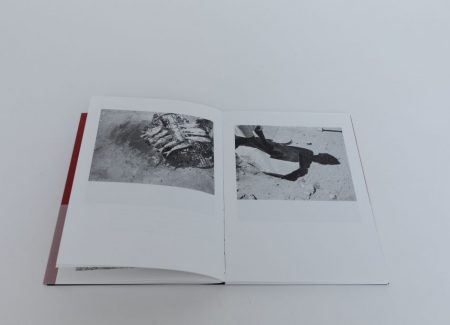

A photograph of a dead bird on the rocky desert appears next to the beginning of the text portion of the book, setting the grim atmosphere for the story we are about to read. A thin strip of the image from the following spread is visible, and opens to a photo of clothes hanging from the trees. Then there is a spread with a large photo of what looks like a skeleton of a cart, left unattended to decay in the deserted landscape.

“Two Men Arrive at a Village” (the story) is printed on several pages placed throughout the book. It begins as a classical narrative, and tells the story of two supposedly friendly men coming to a village. Yet they are not heroes one would expect. These men have come to destroy everything, piece by piece. The infractions begins small, as Smith points out, as they ask for food. She then details the progression of injustice as these two men rob the villagers, murder a little boy, and rape young girls. This story of two men who bring mayhem and violence could be taking place almost anywhere – it has a universal dimension. It illustrates an intrusion that disrupts the rhythms of daily life, family circles, and communities. The story has a profound ending, turning it into a parable of a universal horror.

Back with the photographs, the ending of the story is paired with an image of a decaying cross attached to a dying tree, with graves visible in the background. As we move through the rest of the book, there are images of an exhausted raw-boned horse in the rocky landscape trying to get up, a girl in a bikini holding a plate with a cake, and birds flying over water. Ractliffe’s photographs of aftermath, pain, desolation, and absence complement the sad and horrifying parable. There are intentionally no portraits of people in the edit of the book, to fit the universal dimension of Smith’s story, yet the images do have an enormous human presence.

Smith’s short story is a masterpiece, and placed in dialogue with powerful photographs by Ractliffe, the combination creates a unique experience, as the works of the two women reinforce each other. Placed together they also offer a more nuanced storytelling, inviting us to engage with the more complex histories of the region. Two Men Arrive in a Village is a photobook for those who indulge in both active reading and attentive seeing.

Collector’s POV: Jo Ractliffe is represented by Stevenson gallery in Cape Town, Johannesburg, and Amsterdam (here). Her work has surprisingly little secondary market history, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.