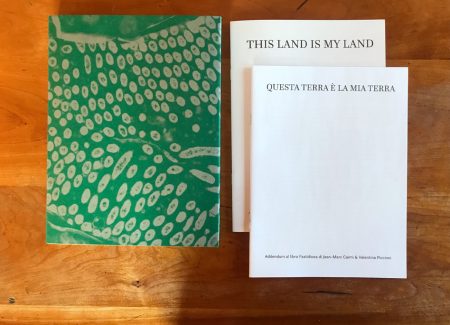

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2022 by Overlapse (here). Softcover (16.2×21.6 cm), 228 pages, with 234 images and illustrations. Includes mixed art papers with one double fold-out, a section-sewn, exposed binding, and a silver-printed dust jacket. With two 28 page addendum booklets containing interviews with farmers, one each in English and Italian. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Stop me if you’ve heard this one. A virulent pathogen attacks organisms at the cellular level, disrupting important metabolisms, leading to systemic illness and death. Unleashed into tightly packed populations with no natural defense mechanism, the disease leaves a wake of widespread devastation within a short period of time. The negative impacts are felt at a biological, economic, and cultural level.

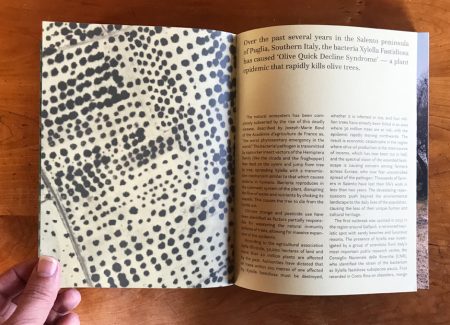

This is the current situation faced by olive groves on the Salento peninsula of Puglia, in southern Italy. Beginning roughly ten years ago, they became infected by a strain of Xylella fastidiosa, a bacteria spread by plant-sucking insects. Fastidiosa restricts the vascular flow of water and nutrients within plant xylem, spawning an awful wasting malady known as olive quick decline syndrome (OQDS). With no known remedy available, EU authorities have resorted to extreme countermeasures. The current prescription is that any olive tree within 100 meters of an infected one must be destroyed. Through the combined effects of disease and human eradication, 4 million trees have been removed to date and 30 million more are threatened, or approximately 95% of Europe’s olive oil production base. It is an ecological car-crash occurring in slow motion, with no clear landing pad.

OQDS is an ugly spectacle, but a tantalizing one for the Italian duo Jean-Marc Caimi and Valentina Piccinni. They devoted six years to photographing all aspects of the Xylella fastidiosa crisis, and as with past projects (e.g., their monograph Rhome, reviewed here), they dove in with all four feet, living in an olive oil mill in Puglia, where they shot nearby farms and processed the project’s monochrome film. Their photographs are collected with archival images in the recent monograph Fastidiosa. Like many titles in the Overlapse catalog, the book incorporates a range of source material into a narrative closer to multi-media history than traditional monograph. It’s a dense, sweeping study, rooted like the olive growing culture in artisan textures and organic palpability.

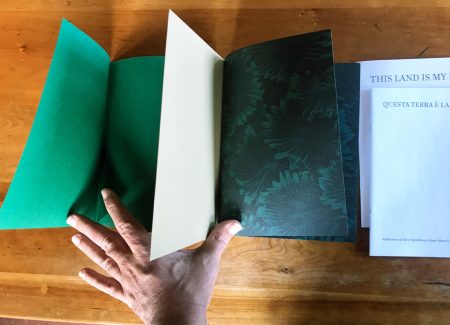

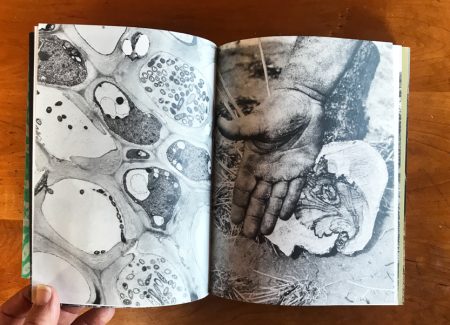

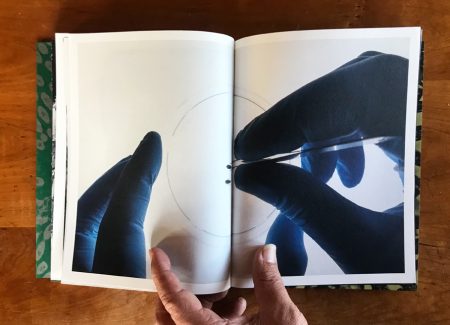

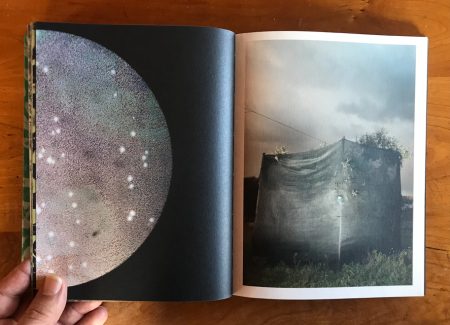

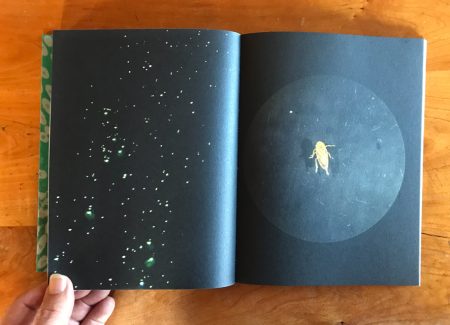

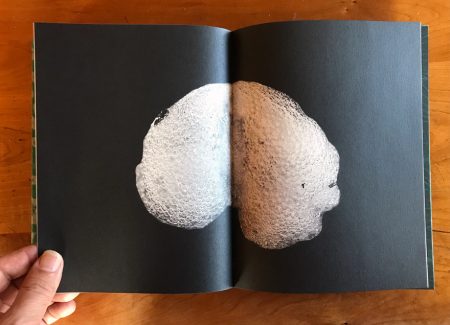

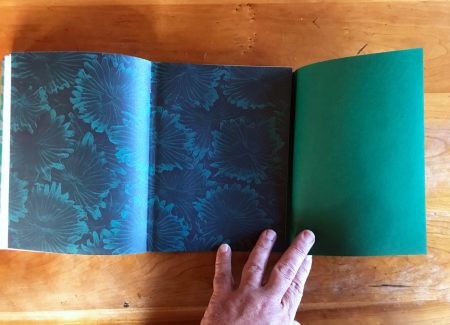

The book begins at the core of the issue, with basic biological function. The hand-printed dust jacket shows a high contrast image of plant guts. Perhaps they are infected with fastidiosa? That’s hard to discern without some scientific training. In any case, the photo’s cell mechanics are subsumed under the beauty of abstracted nature, the effect enhanced with silver ink contrasted against rich green paper. The jacket feels soft to the touch, like rice paper or perhaps an olive leaf. Its tactile quality signals that materials will be treated carefully in this book, a promise kept immediately with the cover itself, an insect silhouette printed on plain cardboard stock atop open bound spine. Here we can peer into the book’s guts on a vascular level. Leafing forward, the end pages switch abruptly to thin uncoated material with tessellated patterns—perhaps electron photography?—like the wallpaper of an Italian villa.

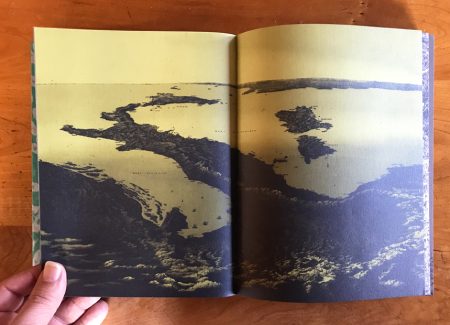

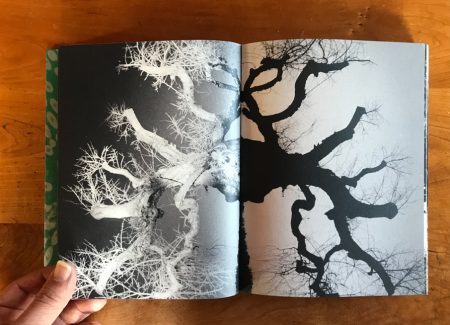

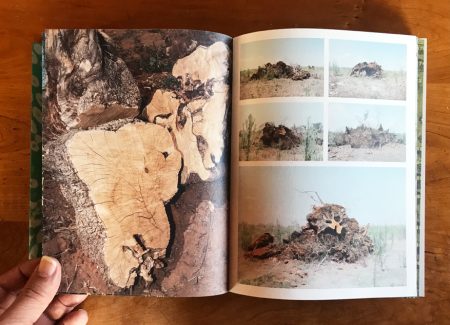

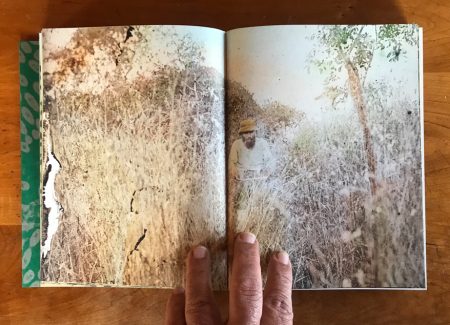

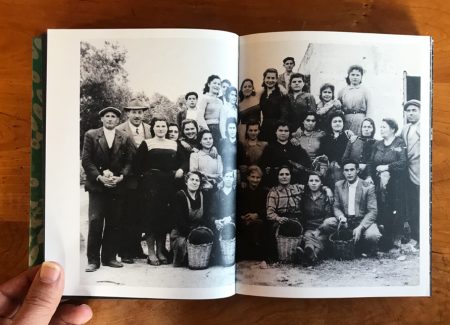

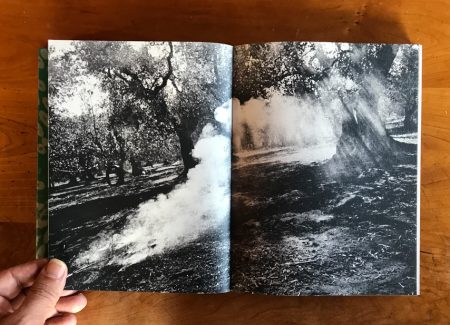

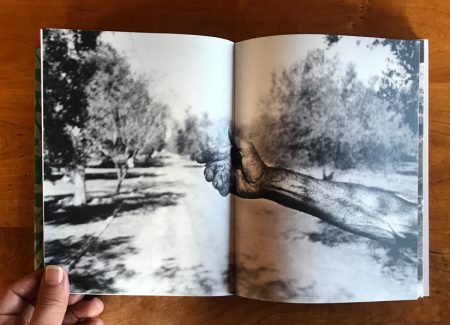

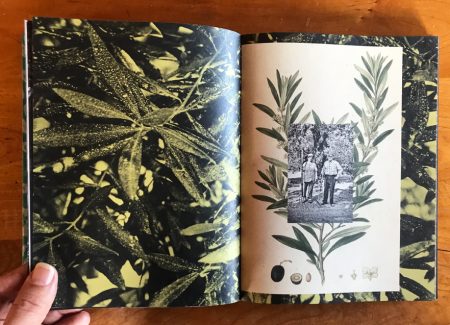

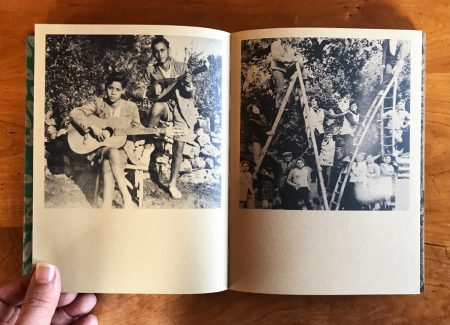

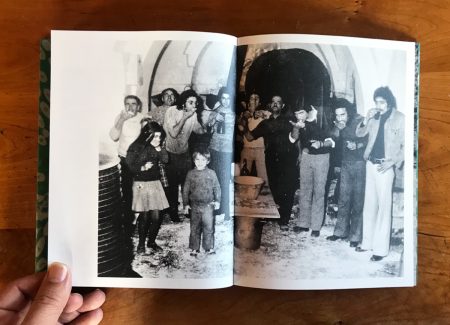

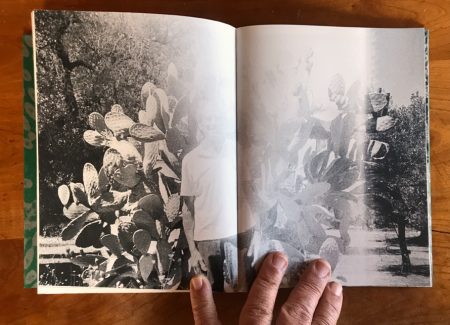

From here a short sequence of photos charts a course for themes to follow – an overview of the Italian coast, tree limbs, shadowy figures, a Madonna and child holding an olive branch (this cruel disease has attacked the very symbol of peace), burning orchards, and an outstretched hand gnarled by farmwork. All are prologue for the book’s primary text, a two-page capsule summary of the crisis which comes about twenty pages in. It outlines basic facts to form a rough framework in the reader’s mind. But the meat of the story is told in images. They begin again after the text with several sequences of destroyed olive groves, but this time in color. We see stumps and charred land. Perhaps to diffuse the bleak present, Caimi and Piccinni choose this point to begin weaving found and archival footage into the mix. An ancient autochrome shows a bygone farmer, followed by illustrations of olive seeds, a girl in a field, an old group portrait of olive pickers, and then quickly back to present day with a picture of a contemporary laborer, looking as and sturdy and determined as any tree trunk.

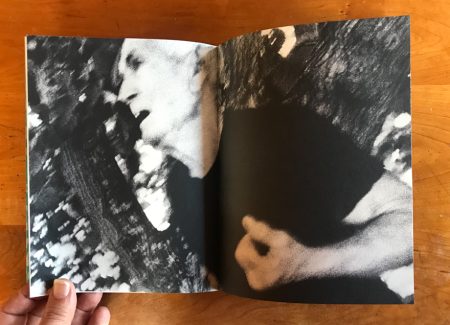

Archival footage provides context throughout. Still, the majority of photos are by Caimi and Piccinni. For the main body they employ a stark impressionistic lens, using motion blur, confused focus, angular cropping, and dramatic lighting to mimic cinematic language. Stripped to monochromatic essence, bacteria looks austere when juxtaposed with a pock marked wall or an old tattoo. Elsewhere it seems more like wood grain. There are strains of Provoke-style Japan, or perhaps Matt Black or JH Engstrom, with a similar foreboding mood. But the visual tone here is more laudatory and uplifted. These Italian skies may be parched but also expansive. One feels the essence of human dignity, the value of hard labor and simple duties. Perhaps the burden of being human is not so different than an orchard charged with bearing fruit? Or an irrepressible bacteria penetrating a cell wall?

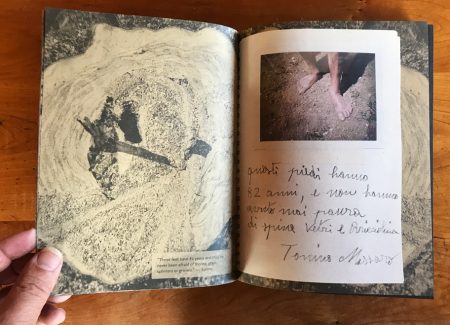

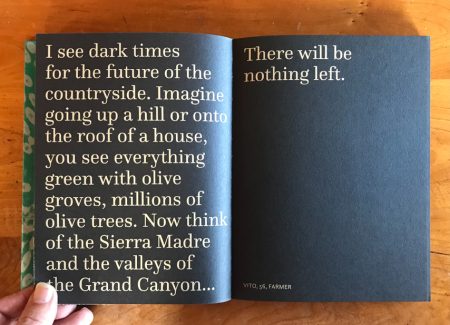

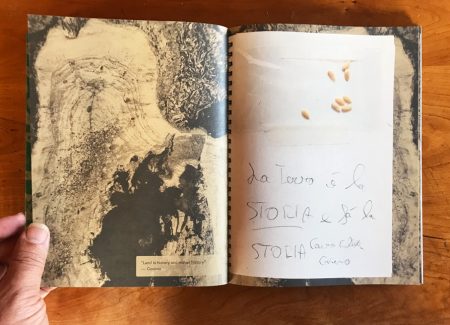

Moving forward, the book follows more detours afield, with clinical specimens, color gels, and contact sheets, before sharper diversions. In a section called Questa Terra E la Mia Terra, scrapbook clippings combine with brown toned landscapes, annotated with alarming drop quotes from olive farmers. The texts vary but they can be roughly summarized by the final quote from Vito, 56, Farmer, spilling in large type across a two page spread: “I see dark times for the future of the countryside…There will be nothing left.” For this section the book switches abruptly to a thin stock. It’s a strong and subtle design element, with echoes of stumped tree rings alternating thick and thin. The hand notices the pages even before the eye. If the reader’s mind has wandered off for a moment to contemplate doomsday scenarios, material choices will keep them firmly rooted.

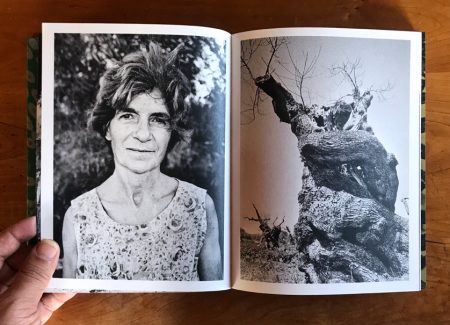

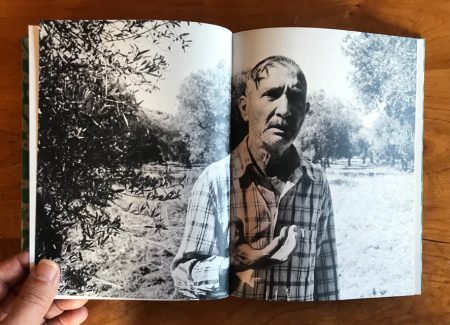

Just as it seems every design trick has been exhausted, Fastidiosa pulls out another, with a centerpiece gatefold opening onto a four page grid of farmer portraits. They appear to be Holga photos, perhaps double exposed? The process details are not specified, but the pictures feel quite human. Many of the faces are smiling or at least looking peaceful. It’s a nice respite from what has generally been a bleak torrent of eco-catastrophe. No matter how hard the circumstances, this section seems to imply, the human spirit is indomitable. Or at least a reader can cling to that notion from an armchair vantage.

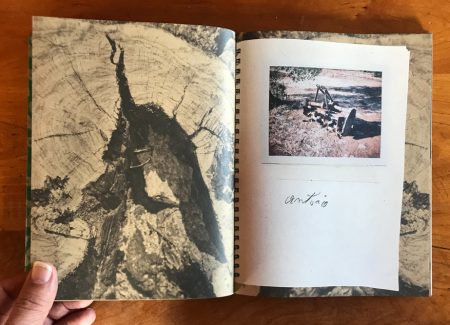

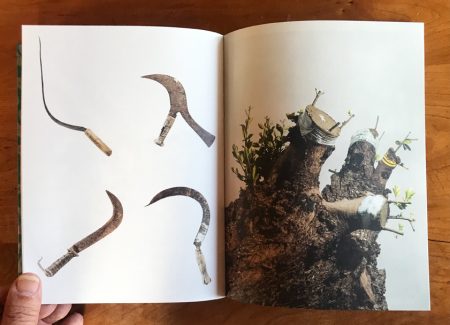

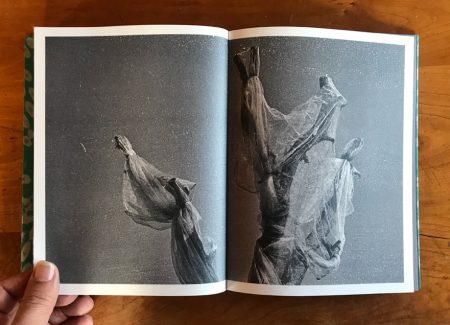

After another thin-paged reprise of Questa Terra E la Mia Terra, the photos take a turn toward lab work, with farming tools and dead branches cast as still lives against blank backgrounds. All the evidence has been collected, and now it’s time for assessment. From this point the approaches spill across genre, as the book hints at various treatments and theories. Close ups, reversal, portraits, old snapshots, interiors, and candids lead finally to a long sequence of sharply pruned trees shrouded in plastic, their futures squelched.

It’s enough to put one in a depressing mood. The enclosed booklet This Land Is My Land is no salvation. It’s relentlessly grim. There are two versions of this addendum, one each in English (slightly beige to distinguish it) and Italian. Take your pick, the outlook won’t change. Farmers interviewed by Caimi and Piccinni spill their thoughts and memories about olive trees, history, heritage, and the current tragedy. Some of the families can trace their groves back over centuries. Livelihoods, homes, and pasts are being wiped away within a few short seasons. A sad, bitter and angry tone prevails, understandably. But what can anyone do? There is no known cure, and farmers must make the best of a bad situation. It’s some small solace to know their oral histories have been documented for posterity. But that does not make them fun to read.

When Caimi and Piccinni began their project in 2015, they could not know exactly where it might lead, nor the circumstances of publication. It’s a cruel irony that the book comes out now, on the fading fumes of a global pandemic. Everyone’s emotional state has been through the wringer these past two years, as have our views of disease, medicine, and the future. Not so long ago it may have been hard to relate to olive farmers dislocated by a pest. That’s probably less true now. We’ve experienced a societal trauma similar to Puglia. But while coronavirus thankfully recedes, OQDS has no relief in sight. This too shall pass. But exactly when is uncertain.

By bearing witness to the problem, this book expands awareness and performs a service. It’s an art world version of hard hitting journalism, and it might be enjoyed on purely aesthetic terms, as a beautifully crafted monograph. But it offers no fix, and it’s hard to come away feeling anything but distraught. It’s a feeling to which we’ve grown accustomed since early 2020. But that doesn’t make it any easier to take.

Collector’s POV: Jean-Marc Caimi and Valentina Piccinni do not appear to have consistent gallery representation at this time. As a result, interested collectors should likely follow up directly with the artists via their website (linked in the sidebar).