JTF (just the facts): A total of 43 black and white photographic works, variously mounted and framed, and hung against white walls in the main gallery space and the smaller project room. All of the works are constructed from standard four frame gelatin silver photobooth strips, with the smallest group consisting of 3 strips and the largest using 48 strips, made between 1969 and 1976. Physical sizes of the works range from roughly 8×4 to 8×78 inches, and all of the works are unique. (Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: While photobooths still have a place at teenage parties and in Japanese video game parlors, they have largely become obsolete in mainstream America. It used to be the case that you could walk into nearly any drugstore in the country, put your money in the slot, sit on the stool, pull the curtain closed, and be blinded by four successive flashes, emerging to receive your strip of headshot portraits. Maybe you needed the images for a passport or job application, or maybe you were just goofing around with your friends making faces, but for many Americans who didn’t have a camera, this was the primary way you could get quick and easy pictures taken.

From a photographic point of view, the photobooth is a classic closed system. There are literally no variables to consider, aside from the height of the stool and the sitters pose or expression. All the technical parameters are fixed – the length of the exposure, the camera angle, the flash, the print processing, etc. – so making photobooth pictures was a rigidly uniform endeavor. Andy Warhol famously posed celebrities and other would-be-stars and hangers on in photobooths, but any genius to be found there was rooted in the eccentric people he chose and the idea of exploring an inflexible and repetitive process to make multi-image portraits. The photobooth was about as mute an artistic partner as possible, cranking out pictures the same way every time.

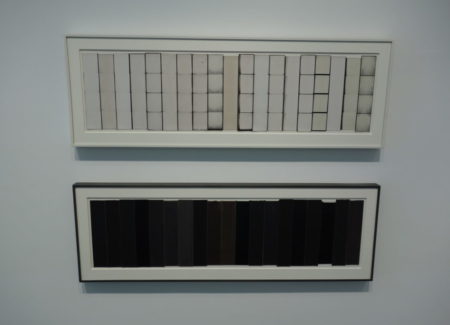

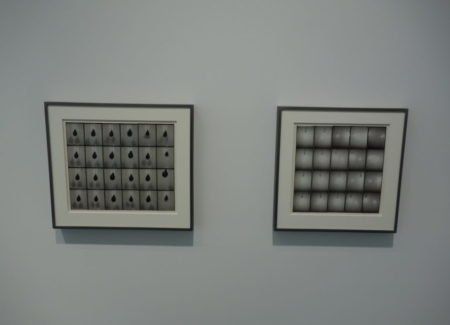

But for Jared Bark, the strict limits of the photobooth offered their own kind of aesthetic challenge. The earliest pieces in this show (from the late 1960s) find Bark trying to understand the baseline functions of the photobooth. An array of all white strips documents the contents of empty photobooths, the tiny variation in color likely coming from the fading/aging of the backdrop material. A second array, this time in all black, was generated by blocking the camera, the range from deep black to dark brown probably a result of processing and exposure variations.

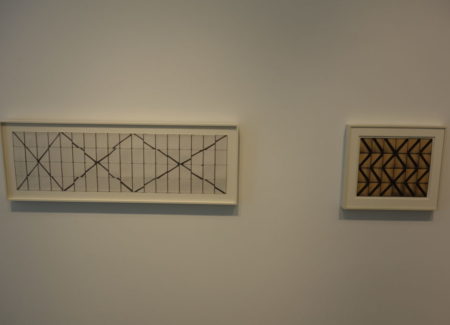

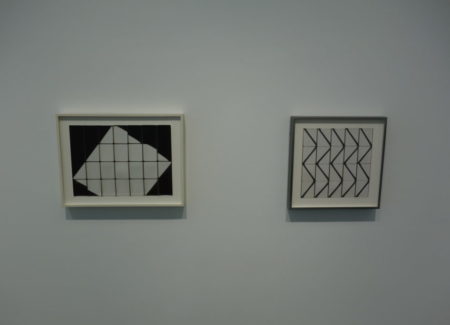

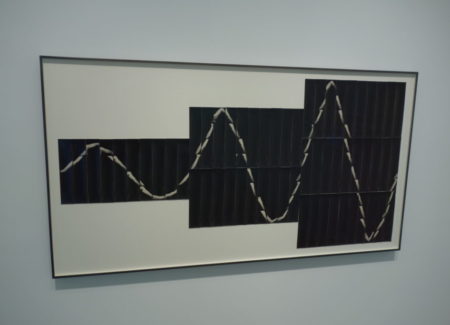

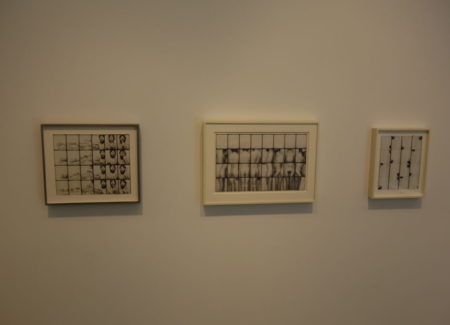

Once Bark had mastered the image making properties of this tool, and could reliably control white and black outcomes, he was able to splinter off in several artistic directions. Geometric abstraction was an obvious path forward, but executing the sequential images in just the right way to create patterns of lines required significant planning and precision. Using angled lines and separations of black/white, Bark creates elegantly simple marching chevrons, growing Xs, and pointing arrows, and even an off-kilter white on black square, where each edge is made up of several meticulously aligned frames.

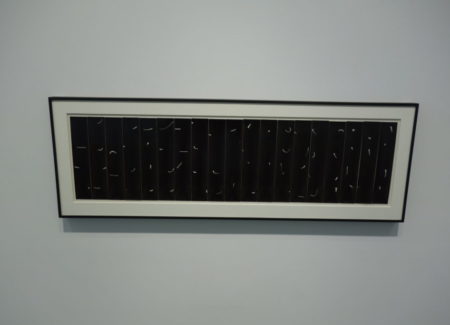

The properties of light inside the photobooth were another area of serial experimentation. Bark hung various bulbs in the cabinet, and then tested the scenarios, from a simple bulb hanging against grey, to white spots against black, to introducing swinging sideways motion, creating iterative blur effects and skipping spots of brightness. And when he wanted a reversed “black” bulb, he took a page from the brainy photoconceptualists and hung an avocado from his wire, improvising a convincing stand-in.

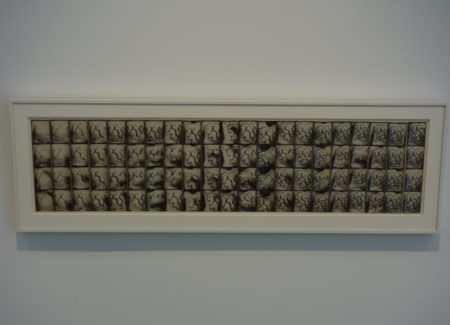

At some point along his photographic journey, Bark acquired a photobooth of his own, so he could try out possibilities that wouldn’t have been easy (or acceptable) in the confines of a drugstore. Many of Bark’s most successful photobooth works introduce a performative aspect to the proceedings, with the artist using his own body as the raw material for sequentially-based compositions. Geometries continue to be part of the aesthetic, with extending arms pieced together into Vs and diamonds, or Bark’s bearded chin used like a dark dot that bounces around from frame to frame. More elaborate progressions are made using a painted circle on an outstretched hand, which iteratively grows and covers it in black (a technique Zhang Huan would use with Chinese characters a few decades later), and expressive paint squiggles self-drawn on Bark’s chest, which build up into a dense nest of interwoven lines. Other works find Bark using a magnifying glass to iteratively enlarge portions of his fingertips to his face, or building a elegantly turned nude self portrait out of slices of his body sequentially placed in the center of the frame. The careful planning required to execute such intricate serial works within the constraints of the photobooth must have been painstaking.

Of less durable interest are Bark’s attempts to bring appropriated imagery into the mix, thereby creating images of images. He’s tried stylized images of both men and women, from wrestlers and weight lifters to explicit pornography, but the rephotography step of bringing the magazines into the photobooth doesn’t add much, except for reordering the media into tightly controlled grids.

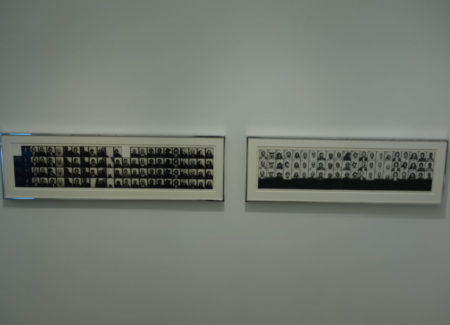

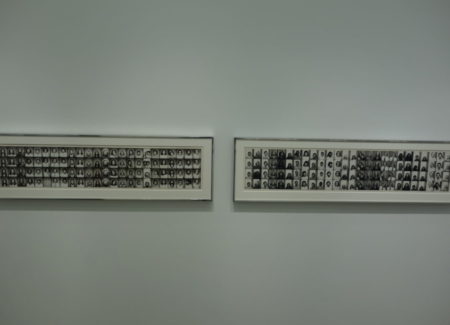

In the side room, Bark walks away from a controlled conceptual use of the photobooth and considers its more obvious role in creating a national cultural archive. So he made cross country road trips where he would gather photobooth strips from strangers in various locations, mounting them together with a strip of himself at that same place. While of course there is a selection from New York, his travels took him to Santa Fe, Reno, Portland, Phoenix, Palo Alto, Las Vegas, and Little Rock (among others), and the faces that emerge from these places mix social democracy with Where’s Waldo artistic intervention (sometimes Bark has a beard, and sometimes he doesn’t, so it’s not always easy to pick him out of the crowd). Each work is a taxonomy of faces, with old and young, male and female, and black and white telling stories of regional differences, early 1970s clothing styles, and performative personalities. And comparing San Diego to Washington, DC, or Berkeley to Provo ends up being more nuanced and discussion provoking than we might have ever expected.

What sticks out about Bark’s range of photobooth pieces is how deliberate they are. They take an overlooked and severely limited photographic process and carefully encourage it to expand in ways that were never intended, ultimately generating artworks that still feel remarkably fresh and lively. It takes a skilled and ingenious technician to understand how a machine can be used outside its original design parameters, and Bark clearly took the time to figure out the ins and outs of the humble photobooth and how he could broaden its artistic potential. In the end, his photobooth pieces feel almost like technology hacks, his innovation coming in developing half a dozen alternate approaches to enabling this everyday photographic system to deliver art.

Collector’s POV: While many of the works in this show are already sold or on reserve, the remaining works are priced between $9500 and $18000. Bark’s photobook pieces have little secondary market history, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.