JTF (just the facts): A total of 35 photographs from three bodies of work exhibited on the second and third floors of the gallery townhouse. The works included are as follows:

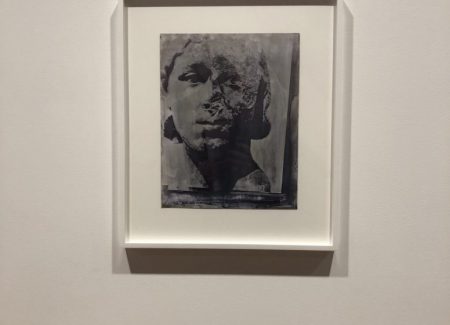

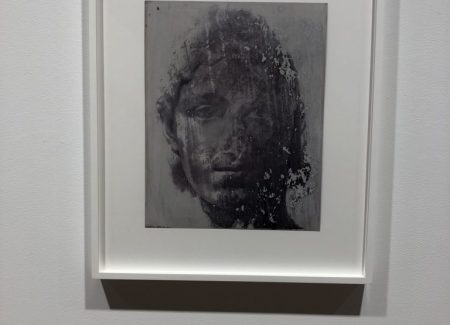

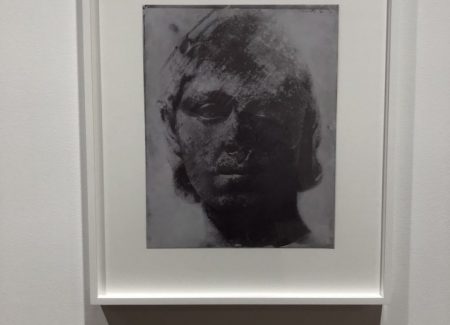

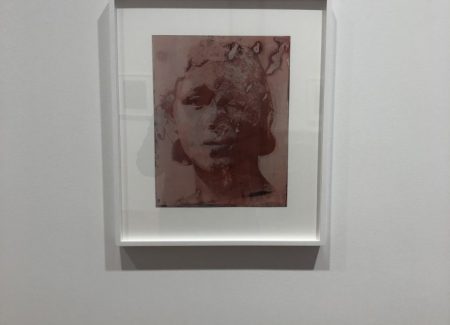

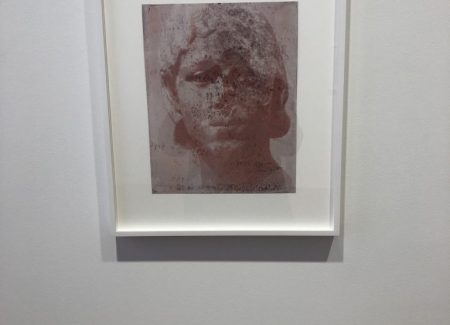

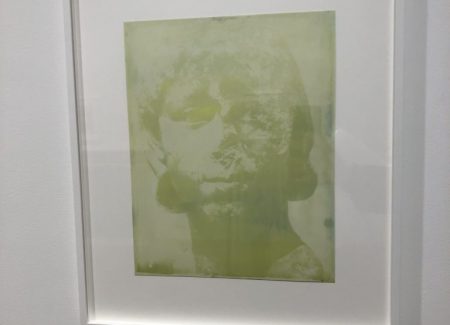

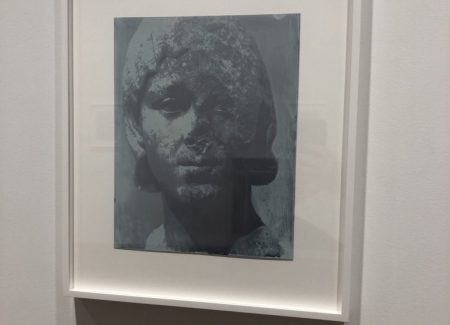

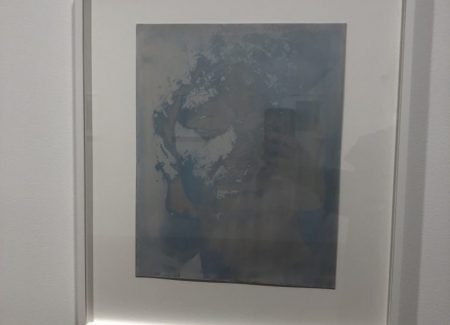

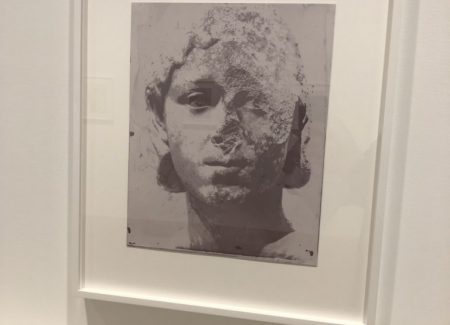

- Julia Mamaea (2018-): 21 gelatin dichromate prints with aniline dye (14×11 inches), matted in white frames and hung in two rooms and the landing of the second floor

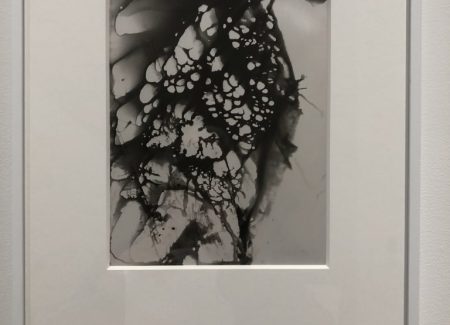

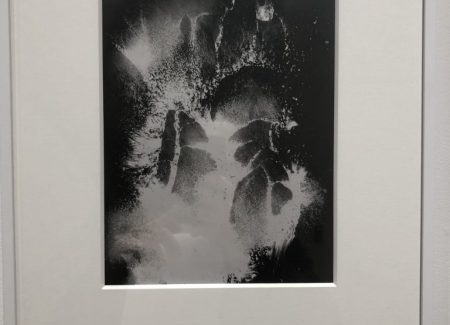

- Chemical (2015-18) 10 chemigrams on chromogenic paper (10×8 inches), matted in white frames and hung in two rows of 5 on the landing of third floor

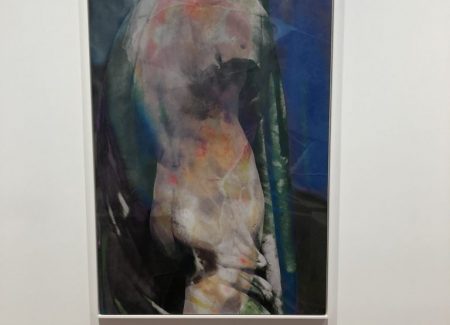

- Bodies (2014-): 4 UV curable ink on Dibond aluminum (roughly 51×34 inches), unmatted in white frames on three of the four walls in the North room

All of the prints are unique. (Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: On a visit last year to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, James Welling became captivated by a portrait bust from the 3rd century AD of Julia Mamaea. One of the “four Julias” from the annals of Roman history, she was a Syrian noblewoman who married into the Severus imperial family and fully participated in the violent intrigue of dynastic politics during that era. To further her ambitious scheme to put her teenage son Alexander on the throne, she ruled the empire herself for several years and had Alexander’s wife, of whom Mamaea was insanely jealous, disposed of. Gibbon had praise for Mamaea in The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire: “Notwithstanding this act of jealous cruelty, as well as some instances of avarice, with which Mamaea is charged, the general tenor of her administration was equally for the benefit of her son and of the empire.” Alexander reigned for 13 years until both he and she excited the wrath of the Roman military for thinking it was smarter to achieve peace with the German tribes by bribing rather than fighting them. With Alexander clinging to her robe, the pair were murdered together in 235AD.

The Met’s sculpture is the material for Julia Mamaea, an ongoing work that is already one of Welling’s strongest. According to the Zwirner press release, he chose the marble head for the naturalism of the carving. It’s likely he was also attracted by its imperfections—much of the right side of her face is missing—and by her personal story. Although Welling doesn’t refer to her biography in the work, he surely knew that the society she inhabited, like that of other regal women in the ancient world, was like a real-world Game of Thrones.

Welling took various photographs of the sculpture, all of them oriented so that her eyes are directed more forward than to the side, and has used the image of the head as the basis for a set of gelatin dichromate prints. Altering only a few variables (color of the aniline dye, light and shade, placement of the head within the frame) he has created 21 closely related but markedly different faces that reflect a gamut of “personalities.” Julia Mamaea had to wear dozens of masks to survive in the Roman court, and Welling has shown us a number of them, from the monstrous to the waifish.

He has explored dimensions of color and texture since 2000 (Flowers, Glass House, Overflow, Seascape) but I don’t recall a series in which the expressive role of shadows have been so prominent. Because of them, the first two of the six heads (both dyed silver-gray) have distinctly opposite miens. One is pale. Welling has printed it with lots of open, smooth spaces in the cheeks and brow. The broken nose and eyebrow are visible, almost painfully so. The lips of the mouth are deeply outlined, as if she were biting down. The adjacent head, on the other hand, is much darker, and uniformly gray. This Julia seems far more “confident.” There are spotty patches of white closer to the surface of the print, as if it had been abraded by age, so that she looks older than the other gray Julia.

In another instance, Welling has added India ink to the dye. The introduction of sepia tones, and the large brown spot he places on her forehead, transforms Mamaea again. She is no longer Roman but Asian or Egyptian. In one of the three violent-tinted heads, she appears to be otherworldly, looking at us from behind a washy veil. Whereas in the two others, she is more earthly, engaged in the here and now, pensive and worried. Depending on which features (nostrils or eye socket) he chooses to block up with ink, Welling can make her ghoulish or girlish.

The series is a departure for him. He has clearly placed limits on himself in the series, changing only a few parameters to test his imaginative resources and ingenuity as a printer. He has adhered to a rigorously frontal view. (Had he revealed more of her hair, we could have seen the marcelled curls that are in the original bust. Perhaps he didn’t want “flapper” associations to interfere.) All of the prints are, like Daguerreotypes, negatives that reverse the subject’s orientation vis-a-vis the camera: in the marble Julia Mamaea at the Met, it’s the right side of her face that’s maimed; in this photographic series, it’s her left.

The series is in part about the social construction of meaning and the human tendency to read characters from a limited set of clues—about facial recognition and analysis, if you will. But it’s also about the history of printmaking. Welling appears to be challenging himself, as Rembrandt did in his Biblical etchings, to evoke diverse responses from a single template and to make the distant past urgently contemporary, to travel across time. The serial portrait tradition of Warhol and Dine and other Pop artists, while also relevant here, feels less vital for him here than his connection to a vaster antiquity.

The modest series Chemical (2015-18) isn’t as much of a departure from his former practice as Julia Mamaea appears to be. The 10 chemigrams here are, like many of his earlier photograms, products of chance and planning. Explosive and lyrical, they are the result of spills and drips and coalescences—natural abstractions from industrial materials—that can take shape on a flat surface and be read as a volcanic caldera or the lacy perforations of a butterfly wing. Resembling stills from a ‘50s Stan Brakhage film, they are like less ambitious versions of the painting-photography, organic-inorganic hybrids that the under-appreciated Brian Wood has been making for decades.

The 4 examples here from Bodies (2018-), shown in a separate room on the third floor, join the classical sculpture motif of Julia Mamaea with the dynamism of Choreograph (2014–2018), which intertwined dancing bodies with fragments of architecture and glimpses of landscape. I don’t find this new series any more satisfying than the old one, despite his valid historical point that “the origins of modern dance derive from early twentieth-century recreations of dance as practiced” in Greece and Rome. Why did he decide that “it seemed appropriate to photograph these dance antecedents,” when the stone bodies depicted are not dancers, per se? His sophisticated application of Photoshop’s color channels and files to decorate these torsos doesn’t lift them off their pedestals or help them achieve release velocity.

Welling has always been a champion explicator of his own work, developed over decades of professing. Which, rightly or wrongly, has often made me suspicious of it. He has a knack for making simple things sound more complicated than necessary. One reason that I was more moved by Julia Mamaea than I have been by a Welling project in many years is that in her fractured stone face he has found an ideal vehicle for his conspicuous intelligence and he has let this eloquent and inspired work do the talking.

Collector’s POV: The works in this show are priced as follows. The Julia Mamaea prints are priced at $18000 each; Chemical at $10000 each; and Bodies at $35000 each. Welling’s photographs have been become more available in the secondary markets in recent years, with auction prices ranging between roughly $2000 and $35000.