JTF (just the facts): Published in 2021 by RRB Publishing (here) and Maison CF (here). Hardcover, 27.5 x 30 cm, 64 pages, with 35 black-and-white and 9 color reproductions. Includes an essay by Damarice Amao (in French/English). In an edition of 1000 copies. (Cover and spread shots below.)

The publication coincides with the exhibitions James Barnor: Ghanaian Modernist at Bristol Museum and Art Gallery (here, from May 17 to October 31, 2021) and James Barnor: Accra/London at Serpentine Galleries (here, from May 19 to October 22, 2021).

Comments/Context: As the history of 20th century African photography gets further researched and filled in by curators, scholars, and historians, with each passing decade more notable names are emerging from the storage boxes and studio archives in each country. The consistent pattern that starts to become visible when comparing artists from across the continent is that practical necessity often led local photographers to start a studio-based portrait business, and within that everyday commercial framework, they then found ways to develop their own artistic voices and styles. This was variously true for Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé in Mali, Samuel Fosso in Cameroon, Sanlé Sory in Burkina Faso, and J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere in Nigeria, among many others both known and unknown in international photography circles. This photobook provides an introductory survey of the work of James Barnor, who primarily built his photography career in Ghana, but unlike many of his African contemporaries, also crossed over to Europe, where he both studied and worked.

Barnor’s story begins in his twenties with his portrait studio Ever Young in Accra, which continued to grow in reputation and influence through Ghana’s independence in 1957 and on through the end of the 1950s. But even in those early days, Barnor wasn’t only a studio photographer; he also worked as photojournalist for both the Daily Graphic and for Drum, the influential South African lifestyle magazine.

By 1959, Barnor felt the need to add to his artistic and technical toolbox, and so moved to London, where he took night classes and eventually enrolled in a two-year program at the Medway School of Art. There he broadened his knowledge of various photographic processes, including color processing, and he ultimately found a job as a professional lab assistant in London while continuing to work for Drum, where he transitioned his focus from local news stories to fashion shoots of multinational models for its covers. By the end of the 1960s, he returned to Ghana (where he would stay for the next two decades) and introduced the first color processing facilities to the country as a representative of Agfa-Gevaert.

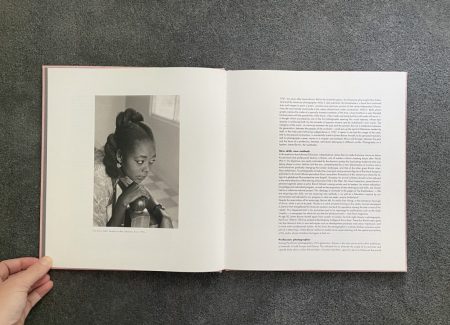

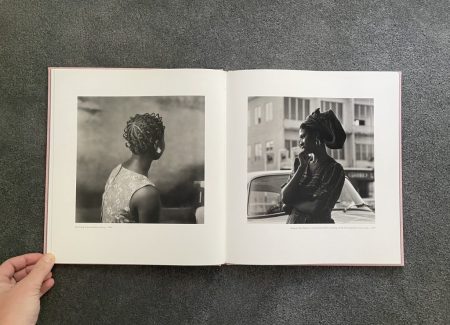

The Roadmaker is a compact summary of Barnor’s photographic career, centering on his artistic efforts between the mid-1950s and the mid-1970s. It makes a quick survey of Barnor’s 1950s work, choosing just a few early highlights in favor of more images made later. A handful of studio portraits from this period find him staying close to traditional aesthetics, with painted backdrops and straightforward lighting framing sitters including a ballroom queen (with white gloves and a crown), a yoga student twisted into angled bend, and a young woman in an embroidered eyelet white blouse. Other works reach out into his reportage work, where he documents political rallies, local dignitaries, and independence celebrations.

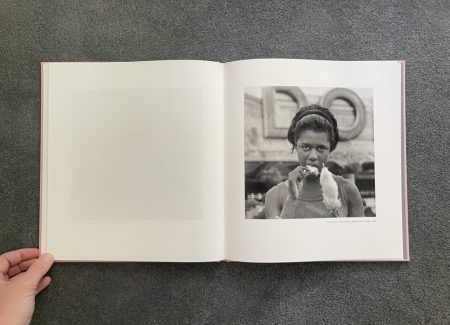

Barnor’s photographs from 1960s London mix more personal images from parties, weddings, and family outings (often featuring the expatriate Ghanaian community), with his fashion work for Drum. An image of Barnor’s wife Elisabeth getting a soft serve ice cream alludes to the nuances of assimilating into British life, as do posed party pictures where Black and white attendees mingle and a white limousine driver grimaces while a Black bride exits his car.

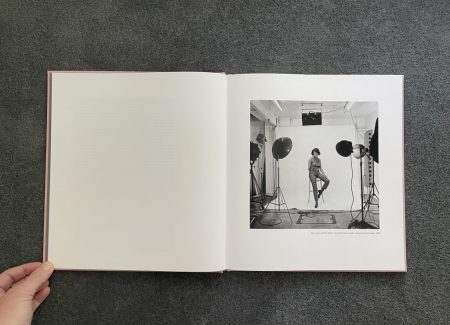

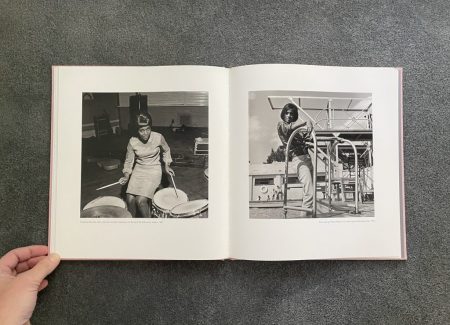

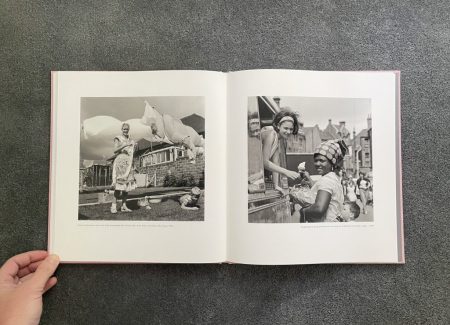

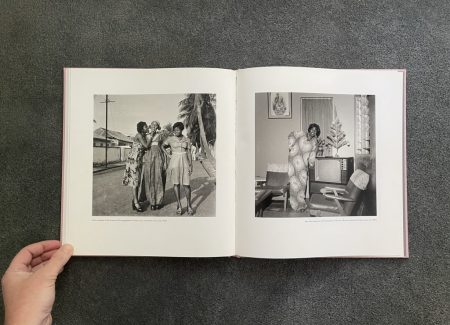

But Barnor’s Drum covers are the real standouts from this period. In the studio, his set-ups embrace the severe enveloping whiteness of Richard Avedon, but they still pop with genuine warmth and glamour. And outside, he opted for more energetic movement, posing his models (of various races) climbing out of a public pool, standing next to a busy children’s playground (in a patterned suit with a red umbrella), seductively eating cotton candy at Battersea Park, banging on a drum kit, and playfully feeding the pigeons at Trafalgar Square. In each case, his models exude easy going self-assurance and stylish individuality, with cool patterned dresses, sleek sunglasses, and even a tied off bare midriff. The looks are on trend for the moment, but more importantly, Barnor was affirming the place of black bodies in public, and encouraging the active mixing of multinational cultural markers.

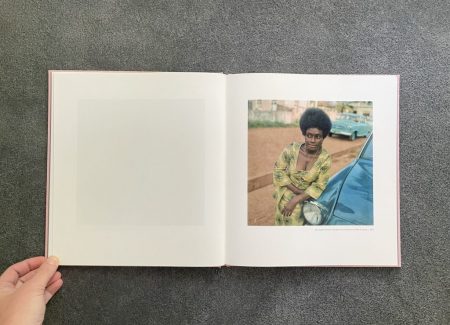

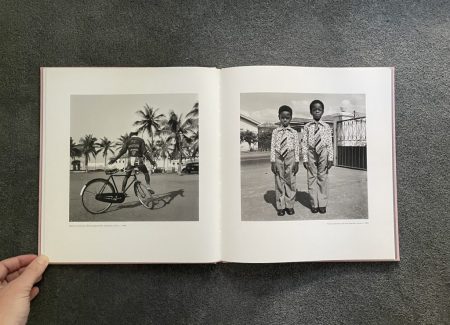

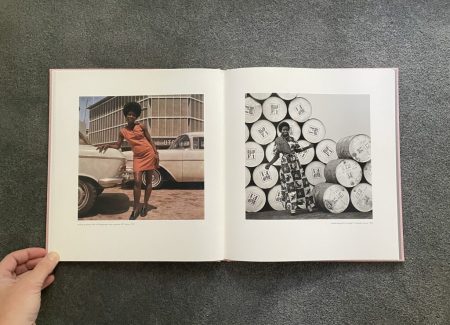

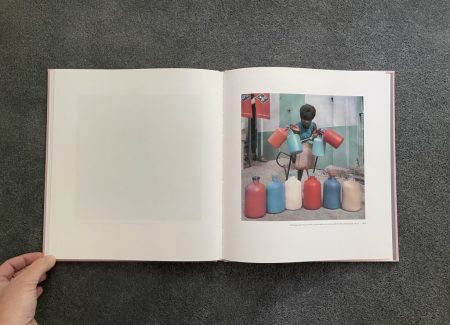

Barnor’s 1970s images back in Accra get even stronger, especially in color, and in many ways, their Afro-modernism starts to echo some of the Black is Beautiful mood Kwame Brathwaite was celebrating in 1960s America. Attractive young models in patterned dresses with natural hair pose near cars and vans, the shiny paint in blue, white, or green, creating visual possibilities for contrast and echo. Barnor also had fun with the Agip oil brand, posing a model near a towering stack of oil cans, and capturing his own studio car (in bold red) gassing up at an Agip petrol pump. And perhaps his most iconic images feature his shop assistant holding a range of colorful plastic jugs outside his store, the red, white, and light blue colors matching the painted walls behind, the red Agfa banner, and the assistant’s dress with jaunty style; and in an intriguing backstory twist, the images were actually composed to be a color guide for the processing lab.

The Roadmaker isn’t a particularly deep survey of Barnor’s work, and its non-chronological sequencing makes it hard to follow along as his career progresses from one location to the next and back again. Future efforts to broaden our understanding of his story would benefit from a tighter adherence to a linear timeline, and a more clear separation between his studio work, his personal work, and his commissions for Drum and other magazines – each is worth studying, and the intermingling here makes the key takeaways a little hard to untangle. The same might be said of the split between Barnor’s black-and-white and color photographs – perhaps there are discoveries to be found if the two were given more space to breathe independently.

But as an initial introduction to Barnor, The Roadmaker succeeds with consistent vitality. Bridging between the world of Africa and Europe gave Barnor a unique perspective, and the best of his photographs simmer with cross-cultural style and verve. They also signal the emergence of a new modern Ghanaian woman, whose warm confidence is altogether contagious. Given the recent interest in Barnor coming from the British photographic community (as evidenced by the two simultaneous exhibitions referenced above), I expect this photobook is just the beginning of a much more robust and wide ranging study of his career.

Collector’s POV: James Barnor is represented by October Gallery in London (here) and Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière in Paris (here). Barnor’s work has not reached the secondary markets with any regularity, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.