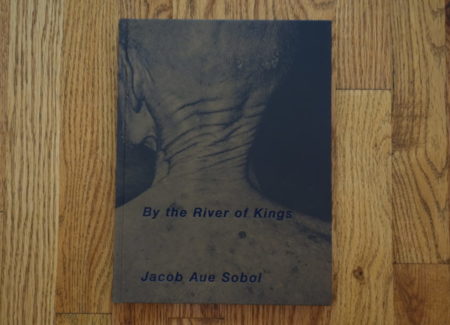

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2016 by Super Labo (here). Hardcover, 152 pages, with 109 black and white reproductions. Includes a short introduction by the artist. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Jacob Aue Sobol’s new photobook By the River of Kings takes its name from the Chao Phraya river that runs through Bangkok, and the resulting images use the ever present waterway as a prism through which we view life in the city. And while Sobol appropriately eschews the saffron robes, glittering wats, and smiling hands-folded greetings of the tourist brochures, his photographs largely skim across the surface of the streets, catching dark glimpses of the everyday hustle taking place along the interconnected canals and spillways. With only a few interludes inside among the private lives of his subjects, he’s mostly captured the down and dirty pulse of what’s taking place out in the open, finding a sweaty brew of simmering menace and gentle tenderness amid the shadows.

By the River of Kings actually comes out of order in Sobol’s artistic career. The images were made in 2008, and were only recently reconsidered and edited into book form. His photographs from the Arrivals and Departures series (reviewed here) were made in the past few years, so it’s a bit tricky to draw stylistic conclusions about this Bangkok work in relation to what he has done since. Most notably, Sobol seems to have sharpened his engagement skills in Bangkok and then patiently refined them on the Trans-Siberian Railway (the setting of Arrivals and Departures), as the newer pictures do a better job of getting inside lives normally closed off to foreigners. In Bangkok, Sobol seems more of a detached wandering observer, digging his fingers into the fluid grittiness of the public drama.

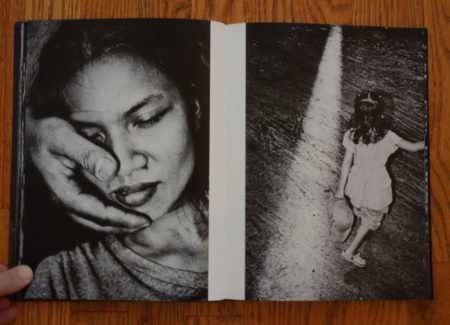

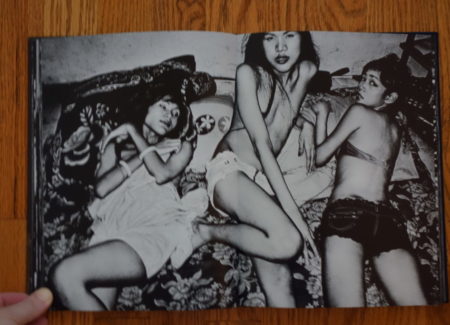

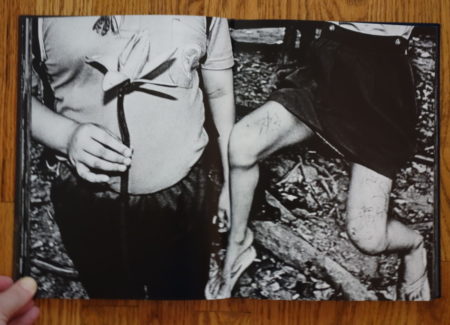

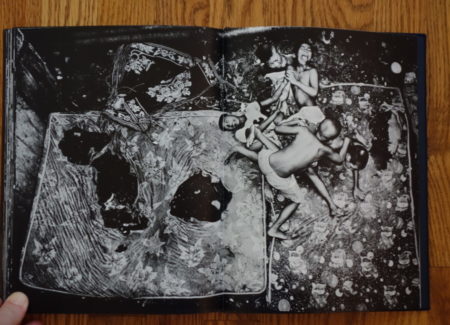

By the cross section of people found in Sobol’s photographs, the riverside neighborhoods clearly house a wide range of humanity, from wrinkled elders watching the world go by with stern-faced weariness to babies and toddlers being given baths in river water. Younger people get most of Sobol’s attention, their openness to his attentions the most genuine, even when it is guarded or wary. Kids swim in the water, dangle from play structures, suffer from bloody noses and bruised shins, wear feathered masks, pee in the street, wrestle in packs like puppies, and sleepily lounge in the midday heat, seemingly unattended and free to follow their fun wherever it leads.

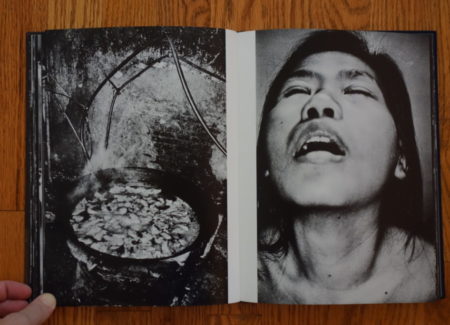

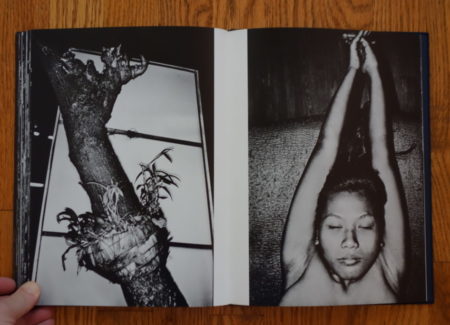

Young women are a subject of their own, their sensual skin rarely covered by more than a pair of short denim shorts. Sobol’s pictures document many forms of female nudity, from casual at home playfulness to bar girl brashness, his pictures often centered less on bodies than on facial expressions. In these eyes, he finds resignation, transporting ecstasy, meditative peace, questioning, sultriness, innocence, fatigue, timidity, and even shame. The shadowy darkness and soft blurs of his style give this catalog of impressions a grim undercurrent, even when a flash of true beauty surfaces from the murky bottomlands.

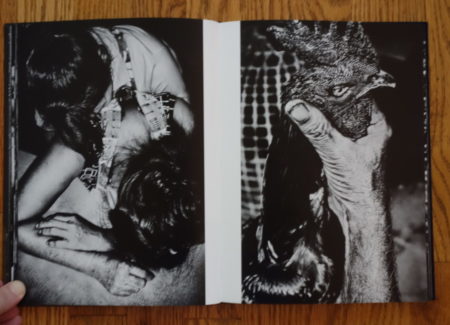

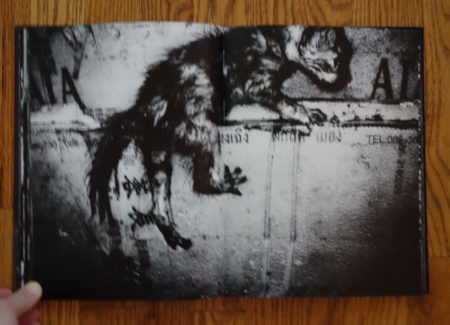

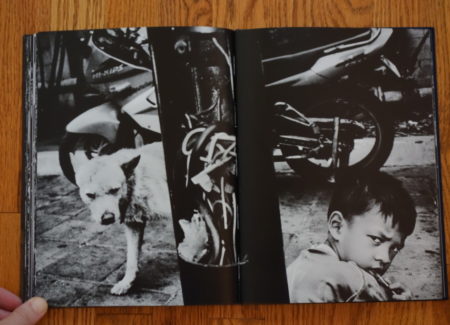

If Sobol’s photographs are any guide, Bangkok is teeming with stray animals. Feral cats and dogs roam the streets, scrounging for food and falling into the river, emerging like drowned skeletons with scraggly fur. More exotic beasts (snakes and alligators) slither through the streets, only to risk having their heads cut off in a spray of black blood. Market chickens, geese, and fish don’t seem to have it much better – hands routinely grip their fragile necks, ever ready for the snap of the killing blow. And even the toy paper birds seem a bit threatening, as if the whole of the animal kingdom was actively facing the dangerous struggle of predator or prey.

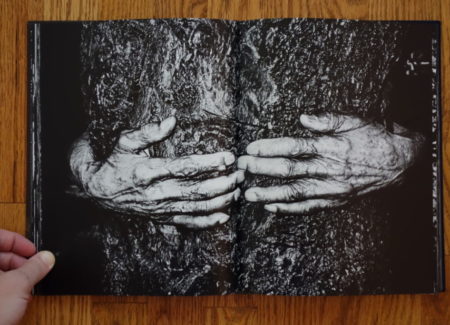

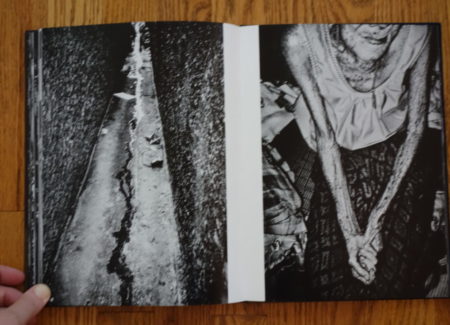

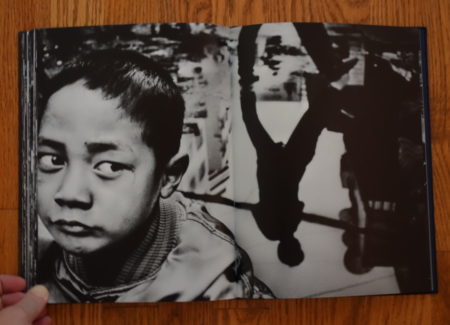

With the river as the central nervous system the city, a murky wetness seems to seep in almost everywhere. Rickety plank bridges provide crossing points for thin canals, but puddles and wet spots still abound, creating reflective slicks that reinterpret the cityscape. Small boats and candle lit offerings float amid the muck during festivals, and trickles of wetness flow down alleys in search of lower ground. Wet hair, damp skin, standing water – the whole river environment seethes with tropical moisture, and Sobol makes us feel that rich slipperiness, our shirts dripping with sweat in the sweltering heat.

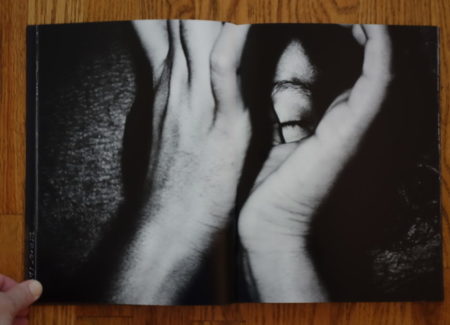

If there is any consistent pattern to Sobol’s images of Bangkok, it is a recurring interest in the textures of the life in the city. His pictures linger in the prickly greenery of hedges, the gnarled bark of a tree, the stubble of close cropped hair, and the bumped cartilage of a rooster’s crow. Here he finds the contrasts and contradictions that seem to epitomize this place – the smoothness of a baby’s skin, the crackled paint of a rusty abandoned motor, the spiky whiskers of an old man, the dense paisley pattern of blouse, and the shiny black back of a beetle on a string. Like a rough brush on the sleeve, his images give us a tactile experience in addition to a visual one, and those touches add to the sensual richness he is documenting.

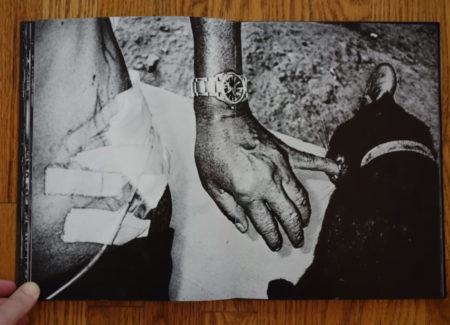

The best of the images in this photobook add a hint of eerie tension to mix. A young boy gives a fearful glance to the side, with a Cartier-Bresson man jumping reflection in the background. A cat bites the finger of a wrist-watched man, his side already covered in bandages. Another young boy watches Sobol carefully as a mangy dog circles around from behind, the frame interrupted by a tangle of wires. And a third boy points a toy gun at him (with an aesthetic nod to William Klein), a pair of disembodied dangling legs hanging ominously from a nearby tree. In each case, there is implied danger in the air, and that ghost of impending trouble seems embedded in river life.

With the horizontal images allowed to bleed across two sides of the spread and vertical ones shown in nearly full page pairs, By the River of Kings offers a visceral experience that seems to extend from its edges. Sobol’s images are crowdingly immersive, in some cases to the point of claustrophobia, bringing us in close to breathe in the stifling air. While not quite as nuanced as his more recent work, these images of Bangkok show Sobol evolving his craft, adapting his style to the foreign environment and finding empathy down the dirty streets and alleys near the water. While there are plenty of shocks to jolt us in these dark settings, it is Sobol’s ability to combine his provocations with a more subtle brand of human engagement that gives the work a more rounded and three-dimensional perspective.

Collector’s POV: Jacob Aue Sobol is represented by Yossi Milo Gallery in New York (here) and Polka Galerie in Paris (here). Sobol is also a member of Magnum Photos (here). His work has little secondary market history, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.