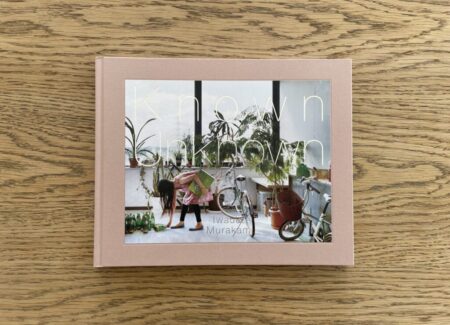

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2024 by Fugensha (here and here). Hardcover, 250 x 201 mm, 68 pages, with 38 color photographs. Includes essays (in Japanese/English) by Junko Takase and the artist. Design by Yui Yamamoto. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Iwauko Murakami’s photobook Known Unknown is one that you could easily overlook or misunderstand. It’s a small thin book, filled with hushed images of contemporary Japanese women going about their everyday routines in the places that they live or work. The daytime moments that Murakami has captured are modest, transitory, and even forgettable, the kind that generally pass by without much friction or notice. And so if you give this photobook a quick browse, you could reasonably conclude that there isn’t much here worth thinking about further. But that would be a mistake.

The backstory to Known Unknown reaches back more than a decade, to the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan. Murakami’s family home is located near where the epicenter of the earthquake hit, and while her family was safe and the artist herself was living in Tokyo at the time, she still felt stubbornly traumatized by the events. So she started making portraits of herself, for her own benefit, to record how she was feeling at that unsettled moment.

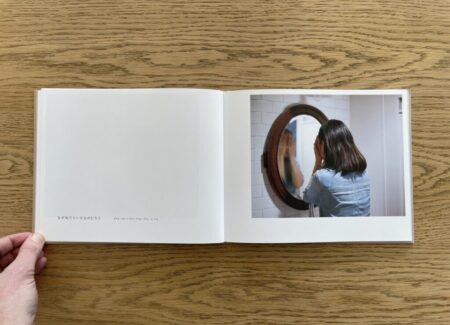

When Murakami came back to those same portraits months later, she felt like they documented a stranger – she wasn’t showing herself the way she was used to, and wasn’t being seen by the camera (or herself as the image maker) in the same manner. She seemed somehow ambiguous, uncertain, or simply not the subject of direct observation that she expected. And it was this realization about the slippery nature of photographic portraiture that led her to the project that became Known Unknown.

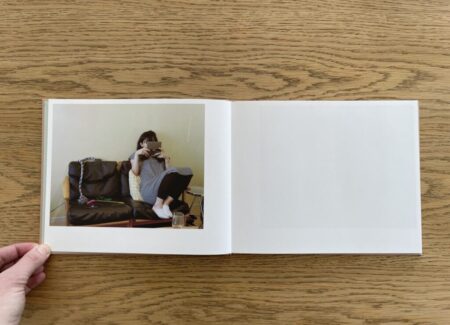

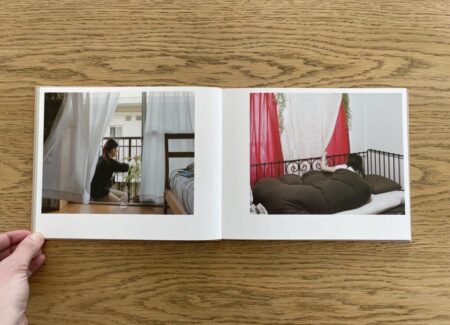

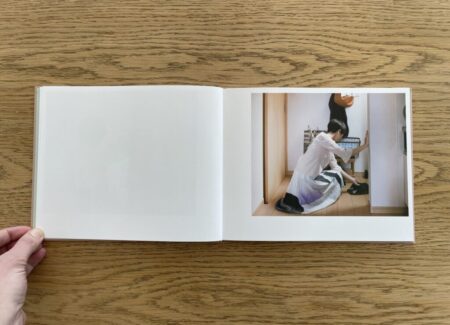

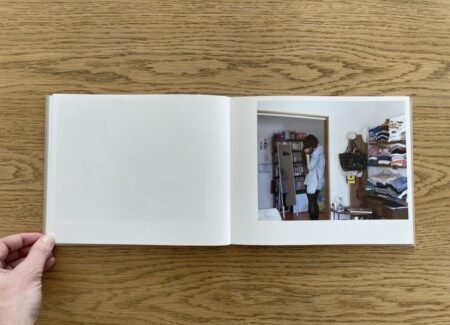

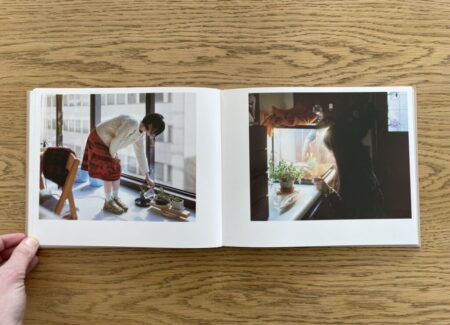

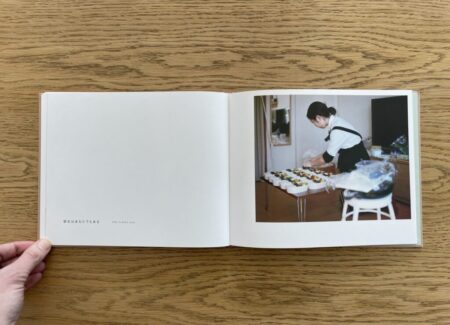

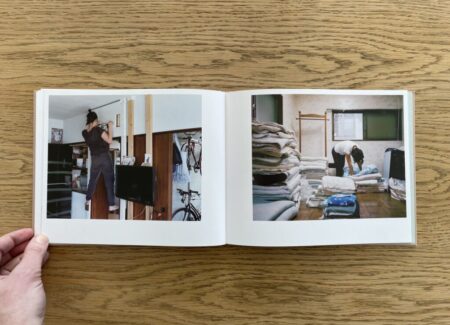

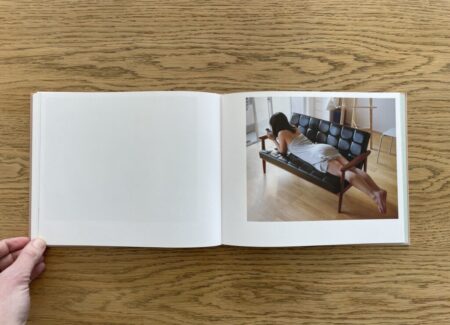

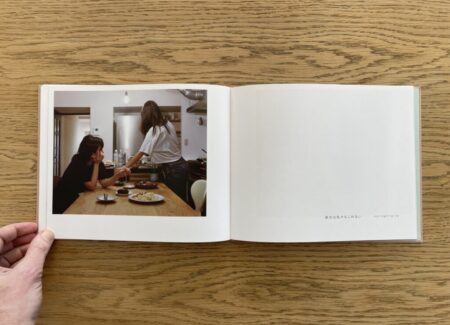

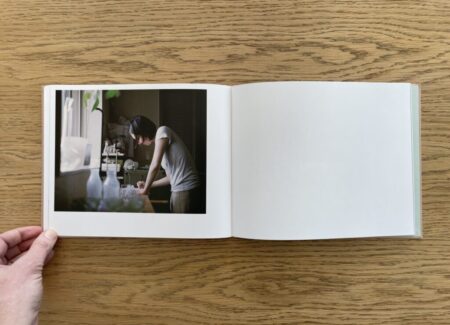

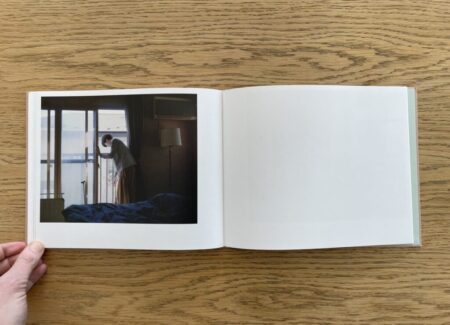

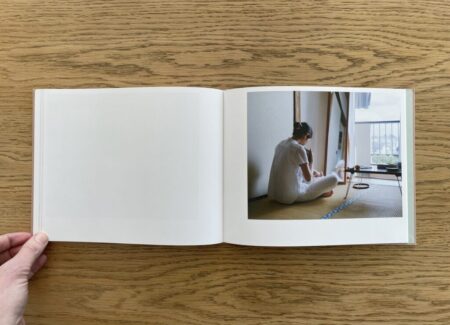

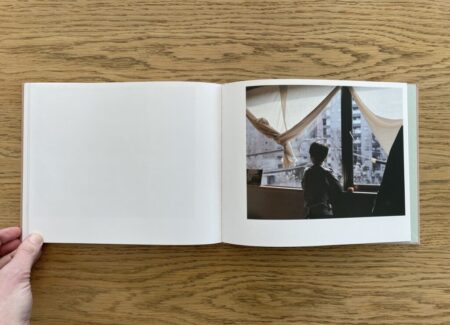

Starting in 2013 and continuing on for the next half dozen years or so, Murakami photographed more than thirty different women as they went about their everyday lives. Many of her models were friends and acquaintances from art school, and she photographed them wherever they felt most comfortable, mostly in their homes, apartments, or workplaces, where they could be natural without paying much attention to the photographer. Her simple compositional template was “a room with a woman”, and unlike most conventional photographic portraits we might imagine, Murakami never photographed the faces or expressions of her subjects.

One way to think about the history of photographic portraiture is to see it as a nearly constant effort to get subjects to stop posing or performing in front of the camera and to “be themselves”. Across the decades, artists have tried countless creative (and sometimes extreme) approaches to get people to reveal their truths, from careful trust building and collaborative patience to waiting for moments of exhaustion and deliberately catalyzing more invasive distractions. The elusive goal of the portraiture exchange has nearly always been the same: unvarnished authenticity, genuine reaction, unguarded openness, bold intimacy, or something approaching the essence of the sitter’s personality, individuality, and innermost thoughts.

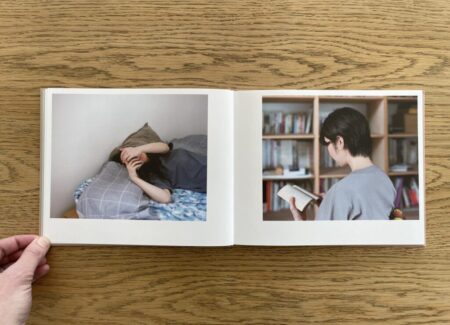

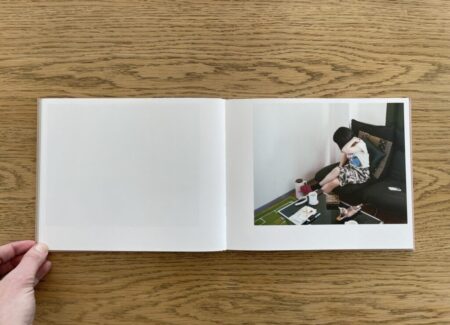

Murakami’s photographs deliberately cut against this bias, with faces that aren’t visible; her subjects are photographed as they are, without being overly conscious of being “seen”. While this is initially a bit frustrating, as we vainly search for the details of a face that will communicate with us eye to eye, this urge to specify eventually settles a bit, and we then start to notice the other things that give the images their life: the body language, the movement of hands, the routines and small tasks, the clothes, the haircuts, the details of furnishings, the light in the space, and the even smaller pauses that take place in between.

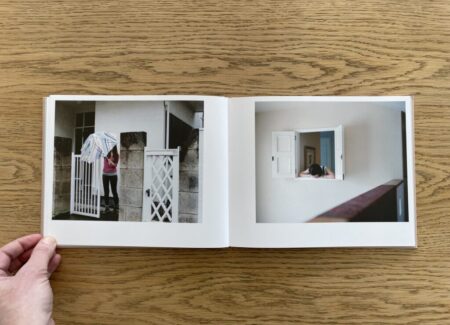

As the pages flip by, Murakami documents a range of softly quiet and altogether underwhelming domestic events. Women look at their phones and laptops, while sitting on sofas or lying in bed. They water plants, put away shoes, sweep floors, feed pets, clean up offices, fold laundry, and mow the lawn. They fix meals, make shopping lists, brush their hair, wash their faces, read a few pages of a book, comfort children, and search for lost things. And now and again, they take a moment for themselves, to rest contemplatively, looking out a window, rubbing their eyes, leaning on their hands, with a pillow over a face, or simply turned away to the side. The patient removal of hair from the cat scratcher (with a lint roller) and the opening of an umbrella are perhaps the most unusual or momentous events in this entire photobook.

In amidst the pages of color photographs, Murakami has inserted three small text captions on blank white pages. They modestly read “why can I tell that this is me”, “she is also you”, and “she might be me”, offering a disembodied voiceover of sorts. Is this the voice of one of the models looking at the pictures of themselves (and others)? Or is this the voice of the artist? Or is this even my voice as a reader, regardless of whether I am male or female? Murakami’s images offer the understated magic of openness – without faces to identify particular people, her figures can be generalized, to the point that I as a viewer can easily insert myself into the various scenes. I can project myself into (or onto) the pictures, and even in their closeness, there is plenty of room in them for me to settle in and feel comfortable.

With this idea in mind, a return flip through Known Unknown feels even more unexpected – nearly every photograph can be interpreted in countless ways, depending on the emotional state the viewer decides to graft onto the images. Is the woman frustrated, or weary, or relaxed, or calm, or anxious, or content, or mediative, or focused, or happy, or on the verge of tears? These photographs can be a mirror to whatever we are feeling, so we see ourselves, in addition to seeing whoever actually inhabits the frames. So many in situ photographic portraits are overtly declarative, seeming to say that this is my place and me in it, but Murakami’s photographs do no such thing. Of course, they are the individualized moments of specific Japanese women, but they function equally powerfully as something more invitingly universal. Removing the faces has encouraged the rest of us to join in, which is a more subtle reversal than is initially apparent.

Near the end of the photobook, Murakami offers a sequence of three views of a woman in a black dress, with her hair falling down to one side to obscure her face. She walks through a doorway, with her hand on the handle, moving forward and then turning around and returning in the opposite direction. Compositionally the frames are structured by a series of verticals provided by white walls and doorways, with a window in the background, but it’s the woman’s movement which is the subject. Is she coming or going? It’s an effortlessly simple setup, but the more I looked at it, the more complicated it seemed to get, with the tiniest nuances of her gestures, the folds of her dress, and the angle of her body seeming to imply different mental states. How we read the pictures might also be influenced by how we interpret the elapsed time between the frames – does she enter and then turn around quickly, as though she has forgotten something, or do minutes or even hours pass between the traverses, making the back and forth more rhythmic? And it is this richly intentional ambiguity, found in nearly every photograph, that gives Known Unknown its durable interest.

This is a photobook filled with inviting entry points and ways in, a bridge builder rather than a statement maker. And in smartly rethinking (and subverting) the dynamics of seeing and being seen, it has offered far more undefined openness and possibility than we normally expect to discover in photographic portraiture. The more I have spent time with Known Unknown, the more I have come to appreciate its unassuming richness. Every image could be the visual prompt for a short story, or many short stories, or simply a moment in a life with countless permutations.

Collector’s POV: Iwauko Murakami does not appear to have consistent gallery representation at this time. As a result, interested collectors should likely follow up directly with her via her website/shop (linked in the sidebar).