JTF (just the facts): A total of 195 black and white photographs (with additional works in a vitrine and 1 video), variously framed and matted, and hung against grey cloth dividing walls on the North and South sides of the lobby area. Nearly all of the works are gelatin silver prints, made between the 1860s and 1961. While a few of the photographers/makers are noted (Mole & Thomas, E.J. Kelty, and others), most of the images are shown without specific attribution beyond the groups they depict.

The exhibit has been organized in conjunction with the International Center of Photography (ICP). All of the works have been drawn from the collection of W.M. Hunt (Collection Blind Pirate). A small pamphlet has been produced in conjunction with the exhibit and is available for free from the gallery; it includes essays by Hunt and Alison Nordstrom. A version of this exhibit was on display at Les Rencontres d’Arles in 2014. (Installation shots below, courtesy of the ICP.)

Comments/Context: In a week that is sure to be flooded with breathless art reporting from Art Basel Miami Beach and its growing horde of satellites and hangers-on, Hunt’s Three Ring Circus is the perfect antidote to the overhyped, celebrity-focused, party-aware, price-flaunting behavior that gives collecting a bad name. This museum-in-an-office-building show starts with a simple premise – that vernacular photographs of large groups of people can be quirky and enchanting – and expands it with the passion and dedication of an insatiably curious mind. The result is a refreshing single collection exhibit that is simultaneously full of eccentric wonders and altogether familiar, an insightful snapshot of early 20th century America where both the personal and the collective are right at home.

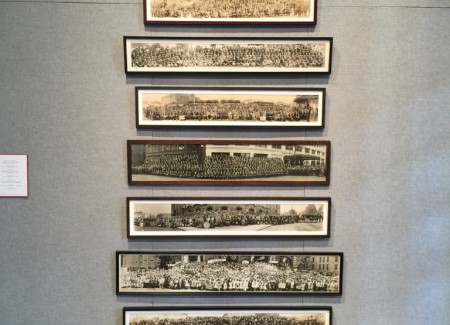

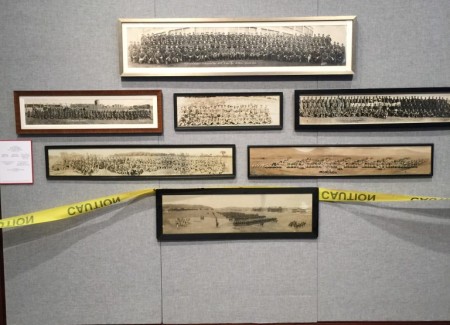

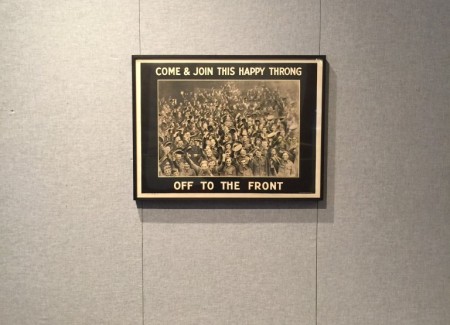

Standing for a formal group portrait has its own special mood – if your family photos are anything like ours, they capture a momentary alignment of conflicting and disparate wills that continuously threatens to burst apart; that any “good” image is actually ever taken is always a small miracle. This show is full of those fleeting moments when the arrangement generally held together, when a handful of people or a crowd of thousands all decided to behave or smile or just stand still, creating a modicum of order out of an otherwise inherently unruly process. Seen as a continuum of formal styles, these pictures offer a staggering range of human geometries, from perfect lines to dense throngs, with layered groups (sitting, standing, on risers etc.), trapezoids, pyramids, and aerial formations all imposed on massed congregations of bodies. Wide format banquet and panorama images spread these ordered assemblages even more broadly, seeming to stretch out so far that they require a slow turn of the head to take them in from end to end.

Part of what is so engaging about these photographic portraits is the balance between the individual and the group taking place – amid the matching costumes, the performative poses, and the staged spectacles, there are faces of very specific people. In the small groups, personalities come through most clearly, and in the largest assemblages, individuals become nearly anonymous. We see personal identity defined by employer, or church, or hobby, or sports team, and can observe the ongoing push and pull of being a member of that group and still finding room for some individuality. And since the historical stories of these congregations, and camps, and military divisions, and fire stations have long since disappeared, these image documents are wonderfully open to interpretation and imaginative thinking. Were these people friends, lovers, rivals, or simply standing next to one another for the first time? What do their faces and poses tell us about their relationships, or aspirations, or long standing disputes? Each and every group portrait is a combination of sociology and psychology, the details of who and why ready to be filled in by the viewer.

As we might expect, there are staples of this photographic genre that appear again and again – military units, high school teams, graduations, annual meetings, church picnics, policemen, secret societies, factory workers, political conventions, and black tie dinners. These feel like familiar pillars of Americana, pictures that represent a sense of collective belonging, rituals that have been repeated year after year like the rhythms of the seasons.

But it’s the oddball pictures that represent the diversity of America with even more plucky resonance. There are beauty contests, chorus lines, synchronized swimmers, ice dancers, and calisthenics being done. There are circus performers, choirs, marathon runners, and golf caddies. There are men in shorts, men in boaters, men in Indian headdresses, and men in bowties. And people hold diplomas, cans of beer, dairy buckets, and watermelon slices. Every eccentricity has its group, and every group has its eccentricity.

Hunt has smartly kept nearly every image in its original frame, turning each portrait into a piece of folk art. Elaborately carved frames jostle with cheap wood ones on the crowded walls, each object seemingly just taken down from the dusty corner of a Masonic hall, school gymnasium, or VFW center. Had they all been perfectly framed in matching mats, we would have missed the tactile quality of their history – their joy is found in celebrating the eclectic, yellowing stories of ourselves, not in the uniformity of museum rules.

What I like best about this show is that it exemplifies the dynamism of smartly intentional collecting. Hunt’s collection is carefully organized and bounded, and yet definitionally large enough to be richly sprawling and inclusive. By imposing his own eye on a relatively forgotten vernacular subject, he has infused it with fresh energy and made it newly relevant. These pictures tell the story of America (and how it saw itself) in unexpectedly nuanced ways, while also expanding our understanding of the surprisingly complex photographic history of the large group portrait. This gleefully eccentric show isn’t like any other photography show on view in New York, which is exactly why it is worth making a detour to see.

Collector’s POV: Since this is a museum-style show in a public space, there are of course no posted prices. While large group vernacular images do appear at auction from time to time, few public comparables exist (aside from the works of Mole & Thomas) and as a result, there is little effective way to chart a systematic price history.

Interesting review.

I enjoyed hearing MW Hunt talk about his photography collecting experience at the Format Festival in Derby a year or two ago. He’s contrary, funny, and candid – and very entertaining – but if you have a train to catch don’t even think of sneaking out before the end as it will not go unnoticed.

Hoped to talk to him afterwards as we all spilled out into a group exhibition but he was collared by someone who won herself a freebie impromptu portfolio review where he politely scrutinised every picture for a very long time, which I thought was immensely kind.

I’d wondered if you two had ever met up, LK.

Interesting vintage 20th Century collection.

Good review…

Jason

http://www.macuha-artgallery.com