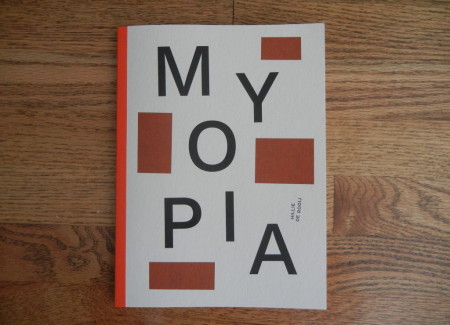

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2015 by The Eriskay Connection (here). Softcover, 72 pages, with 65 black and white and color photographs. Includes an essay by Jan Postma. In an edition of 500. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Dutch photographer Hillie de Rooij’s newest project has a clarity of conception that is both unusually elegant and quietly provocative. It’s like a simple scientific hypothesis, ready to be faithfully tested – have we become so used to the pictorial stereotypes of what Africa supposedly looks like that we have stopped actually looking? Do we effectively photographically find what we expect to find instead of what might actually be there?

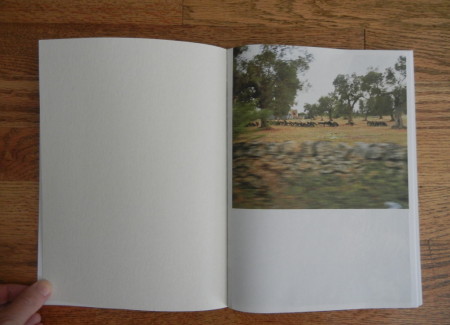

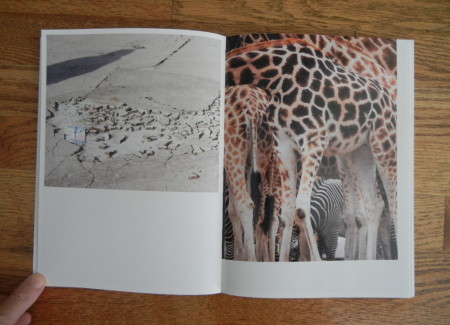

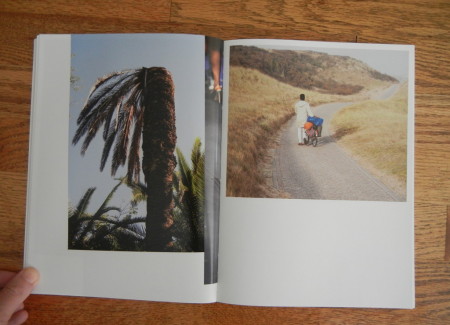

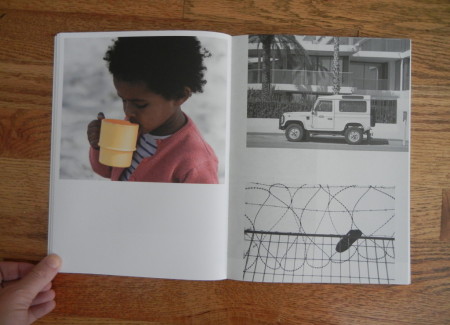

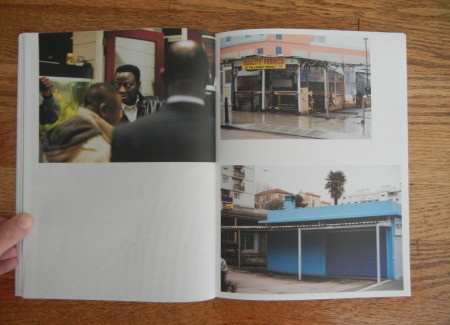

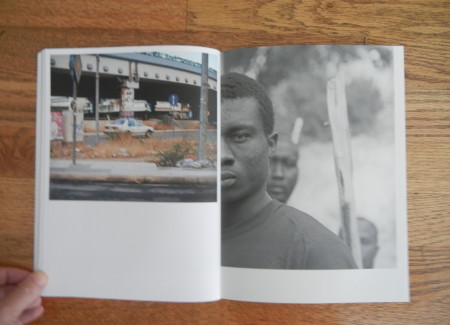

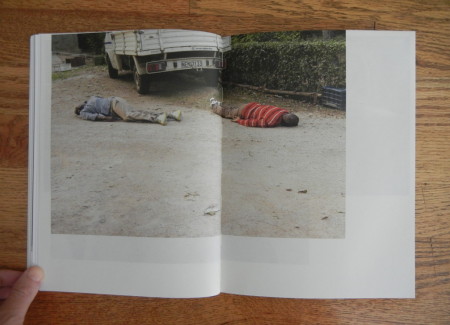

Her multi-layered experiment to discover the answer has undeniably been cleverly devised and implemented. De Rooij started by gathering up images of Africa found in European newspapers, magazines, and other periodicals, and she then sorted them into piles of like subject matter. What she found was a selection of visual tropes and patterns that were repeatedly used to pictorially describe life on the continent: sand and drought, wild animals and palm trees, reclining men and plastic, among a handful of others. Using these clichés as guides or “codes” (effectively instructions), she went on to take her own images in various places in Europe. Her photobook is a collection of what she produced using these rules, and it’s a scarily effective doppelganger of what Africa looks like in the press, even though none of the images were actually taken there.

In page flip after page flip, she pushes on our preconceived notions. Giraffe? Parched rocky land? Spiky scrub brush? Wide vista with huge sky? They’re all here. Things get even more nuanced when we see dark skinned men sleeping in the street. Or battered pickups and Land Rovers. Or a child drinking from a worn plastic cup. Or a plastic gasoline can. There is a sense that these are refugees, or aid workers, or chronically unemployed (or underemployed) men. A dusty airstrip, some dilapidated concrete housing, some improvised market stalls made of corrugated tin and plastic sheeting – they seem to say third world poverty. A man at a bus stop, a stand of palm trees, a woman carrying a bucket – we must be near a small rural village. And yet these familiar reactions and hackneyed conclusions are exactly what de Rooij is getting at – they’re all wrong, and they’ve been ingrained in us by decades of imagery like this, so much so that we have a hard time escaping these assumptions. She’s made Europe look like “Africa” (even down to the plastic suited health worker protected from some infectious plague) and we’ve taken the bait, hook line and sinker.

De Rooij has gone one step further in her investigation of these tropes in the way she has constructed this book. Three different page stocks have been used, with three different printing styles, each meant to evoke a certain venue for the imagery. There are halftone images on thin newspaper meant to evoke a journalistic context, thicker stock with a glossy sheen reminiscent of a tourist brochure, and matte surface paper with the spare elegance of an art book or white cube gallery. She’s effectively created a matrix of combinations, where the photographs might be read in alternate ways depending on their setting. These printing choices reinforce the sense of viewpoints being controlled for different audiences, and of imagery being tailored for a specific purpose.

While the conceptual inversion de Rooij has exploited may look simple at first glance, her approach to unpacking its prejudices is well thought out and hard hitting. It deftly blows apart the premise that these visual codes don’t exist, or that we are somehow immune to their influence. Her smart photobook upends passive looking, forcing us to see content as part of a larger and more complicated framework of external factors. In a sense, she’s artistically “appropriated” a set of distressingly pervasive cultural assumptions, and by applying them to another subject, she’s exposed both the inherent ridiculousness of their truths and implicated us all for being so easily manipulated.

Collector’s POV: Hillie de Rooij does not appear to have gallery representation at this time. As such, interested collectors should follow up directly with her via her website (linked above in the sidebar).