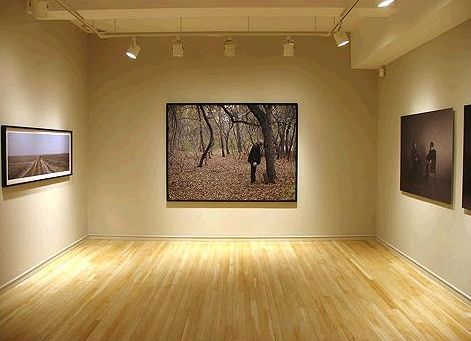

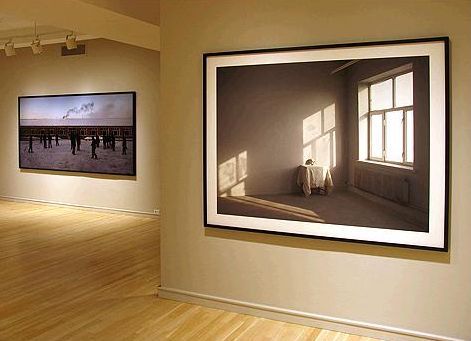

JTF (just the facts): A total of 9 large scale photographic works, generally framed in black and not matted, and hung against red and putty colored walls in the divided gallery space. The prints are either pigment or LightJet prints mounted to Dibond, available in editions of 5, 8, or 12. Physical dimensions range from roughly 20×62 to 55×110, with each image its own specific size. There are 8 color single images and 1 black and white triptych in the show. All of the works were made between 2007 and 2009. There is no photography allowed in the gallery, so the installation shots at right are via the Pace/MacGill website.

JTF (just the facts): A total of 9 large scale photographic works, generally framed in black and not matted, and hung against red and putty colored walls in the divided gallery space. The prints are either pigment or LightJet prints mounted to Dibond, available in editions of 5, 8, or 12. Physical dimensions range from roughly 20×62 to 55×110, with each image its own specific size. There are 8 color single images and 1 black and white triptych in the show. All of the works were made between 2007 and 2009. There is no photography allowed in the gallery, so the installation shots at right are via the Pace/MacGill website.

Comments/Context: One of the main criticisms of the recent boom in Chinese contemporary art was that much of the work seemed to have been specifically made for Western audiences and collectors: big, bold images, full of Chinese cliches and Western consumerism, easily reproducible by armies of staff members; in short, the ultimate get-rich-quick luxury commodity. Hai Bo’s photographs clearly come from somewhere much more authentic and personal. His recent works examine small contemplative moments of quiet, where the burdens of time weigh heavily, and where the people in his pictures have the chance to consider both their own mortality and their place in the larger span of history.

Most of Hai Bo’s subjects are elderly men, perhaps moving a bit more slowly than in their busier younger days. His images capture the rhythms of endless days, where lonely figures walk on desolate roads amid the frozen stubble of winter fields and handfuls of men sit on garden seats, trading stories and taking stock of village life on a rural timescale. One man leans his head against the trunk of a tree, in a gesture of supplication or anguish, while another wrinkled face peers out from the darkness, the plastic ear bud dangling from one ear the only clue to his modern existence. These are the men left behind by the wave of migration to the big cities, born into a world of agriculture and living out their twilight years fatigued and forgotten, some recast as faceless black silhouettes clustered outside a frigid nursing home.

Most of Hai Bo’s subjects are elderly men, perhaps moving a bit more slowly than in their busier younger days. His images capture the rhythms of endless days, where lonely figures walk on desolate roads amid the frozen stubble of winter fields and handfuls of men sit on garden seats, trading stories and taking stock of village life on a rural timescale. One man leans his head against the trunk of a tree, in a gesture of supplication or anguish, while another wrinkled face peers out from the darkness, the plastic ear bud dangling from one ear the only clue to his modern existence. These are the men left behind by the wave of migration to the big cities, born into a world of agriculture and living out their twilight years fatigued and forgotten, some recast as faceless black silhouettes clustered outside a frigid nursing home.

There is a marked sense of poignancy in these pictures, a depressing empty feeling that these men are repeating the age old ritual of being ground up and erased by the tides of collective history. For these individuals, the struggle for meaning against the backdrop of centuries of Chinese history seems palpably real; the hardships are many and insignificance once again knocks ominously on the door. Hai Bo takes an unwavering glance at these lives, and his photographs provide a compassionate, but ultimately heavy-hearted foil to the popular narrative of China’s ever-accelerating economic transformation.

.

Collector’s POV: The prints in this show are priced between $16000 and $40000. Hai Bo’s photographs have recently begun to enter the secondary markets, with prices ranging between $5000 and $44000 at auction in the past two years.

Collector’s POV: The prints in this show are priced between $16000 and $40000. Hai Bo’s photographs have recently begun to enter the secondary markets, with prices ranging between $5000 and $44000 at auction in the past two years.