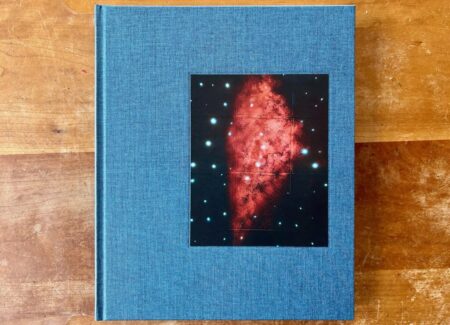

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2024 by MACK Books (here). Embossed linen hardback with tipped in cover image, 24 x 29 cm, 112 pages, with 62 color photographs. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: When the Buffalo Bills lost to the Kansas City Chiefs in the AFC title game last month, hometown football fans absorbed the outcome with familiar resignation. Not only have the Bills never won a Super Bowl (in winless company with the city’s NHL Sabres), they’ve refined the art of clutch playoff losses. Some years they come closer than others, but every result has so far been the same. At this point the “Wide Right” curse is engrained in the city’s civic ethos, regrettably dovetailing with economic trends. Buffalo was once the first electrified city in the US. At various points in the 20th century it hosted the world’s leading grain port and the world’s largest steel mill. But the boom years eventually cycled into rust belt decline. Buffalo has lost half its population since 1950, as its industrial base has been inexorably downsized and outsourced.

Playoff losses and closed plants are just a few of the thousand cuts inflicted on the city in recent decades, but Buffalo isn’t dead yet. Far from it, a spirit of resiliency keeps the city chugging along. There may be salvation yet in a Josh Allen jersey or a beef on weck. Just ask WNY native son Gregory Halpern. Born in 1977 in Buffalo, he grew up on the city’s north side before transplanting to nearby Rochester, where he now teaches photography at RIT. If Buffalo has been a disappointment to some Las Vegas bookmakers, Halpern is one book maker who hasn’t given up hope. “Certain people would say the city is dying,” he once told Aperture, “but it’s also continually being born.” Halpern has been photographing Buffalo’s various deaths and rebirths for the past twenty years or so. Many of his excursions have occurred in the snowy season, and for a while the working title of his longterm project was “19 Winters / 7 Springs”.

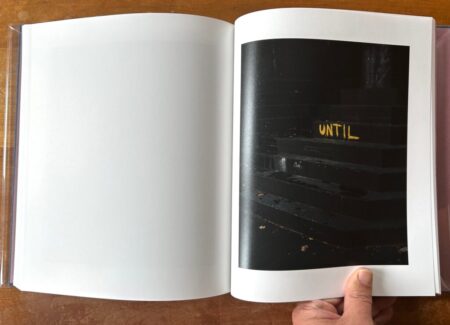

Selections from “19 Winters / 7 Springs” appeared here and there as Halpern was working, including a 2024 exhibition at the George Eastman Museum and a 2017 selection in Aperture. After many fitful years sharing, wrestling, and sequencing the photos into finished form, Halpern has finally published them as a photobook. King, Queen, Knave uses the same cover image as the old Aperture, while its freshly conceived title offers a nod to gamesmanship and shifting notions of identity. Both motifs lurk throughout the book, alongside grimy snowbanks, pitched eaves, and a totemic white deer named April (a local celebrity in Buffalo’s old first ward).

Although Halpern has been photographing his home town for two decades, you wouldn’t know it from his previous monographs. Each of them seems curiously determined to avoid Buffalo. His debut book Harvard Works Because We Do was set in Boston, while its successor A (reviewed in exhibition form here) explored nearby rust belt cities. The next flurry of photobooks included Omaha Sketchbooks, set in Nebraska; Zyzyxx, set in Southern California (reviewed here); Confederate Moons set in the Carolinas; and Let The Beheaded Sun Be, set in Guadaloupe (reviewed as part of a museum group show here.)

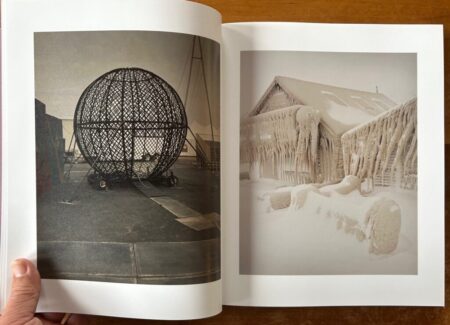

Even if they didn’t feature Buffalo as a subject, these predecessors shoveled a snowy path toward King, Queen, Knave. In retrospect, it was probably Zyzyxx which gave the sharpest clues to what was coming. Aside from its obvious similarities—the two books share similar dimensions, aspect, design, and cover abstraction—there are deeper currents. Zyzyxx blended social landscapes and informal portraiture into a bleak verdict on Southern California. The pictures were simple and carefully framed, almost claustrophobic in their proximity and singular focus. The famous California desert light provided connective tissue throughout, but under Halpern’s treatment it did not feel especially warm. Instead his golden tones imbued subjects with a wan patina, as if the photos were exposed through a squint.

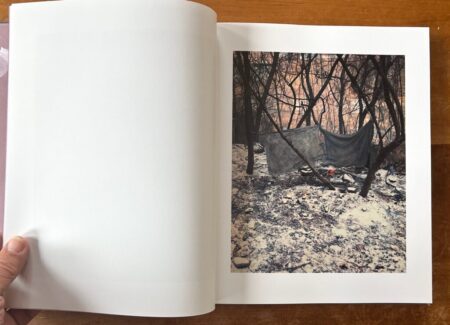

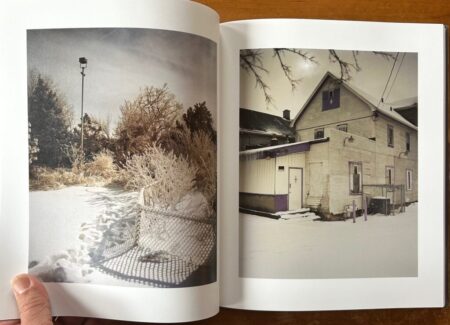

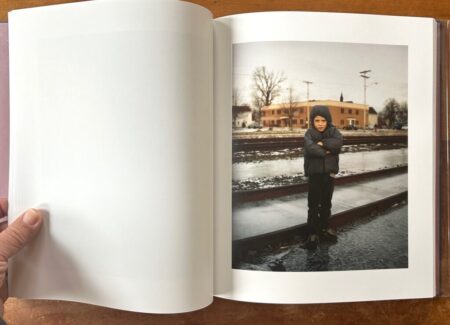

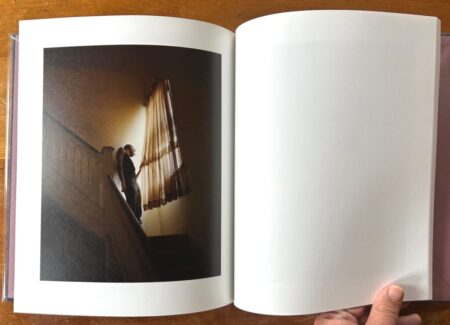

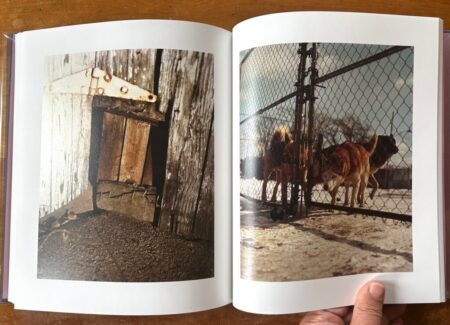

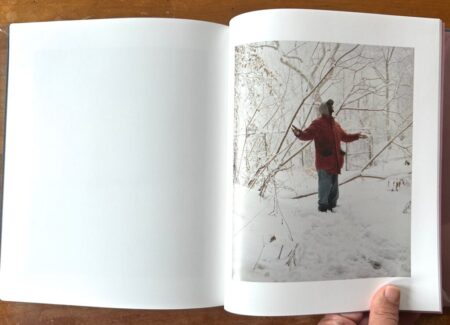

Across the country in Buffalo, King, Queen, Knave leans into a similar color gamut. But this time it is winter weather creating the effect. The first quarter of the book hops from one subdued snowscape to another, each one subtly different. An old house covered in rime ice. A small boy huddled by train tracks. A torn chain link fence behind scattered snow flakes. A frozen checkerboard on Halpern’s porch. In the title photo we’re presented with a jigsaw of blank forms, as a white door, cross, and snow clumps compete for insignificance. Who knew there were so many whiter shades of pale? In a recent presentation about the book, Halpern labeled his palette “a muted dirty kind of white” and explained how it informed the sequencing. “I wanted that heaviness to open the book.”

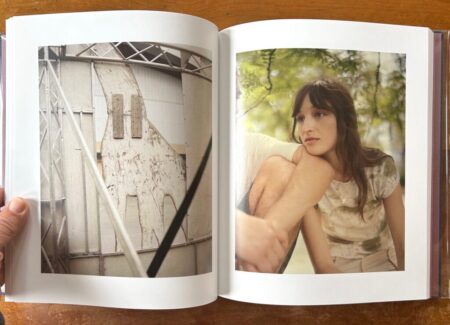

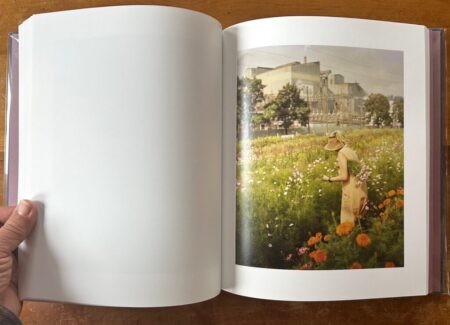

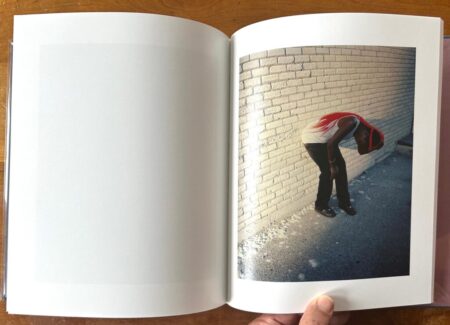

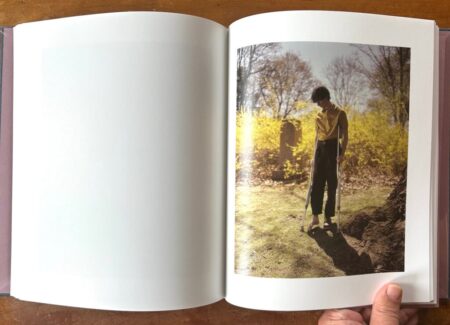

To his credit, the book doesn’t stay heavy for long. A picture of tulips blooming near thawed snow—presumably shot during one of the “7 Springs”—signals a sea change. The sequence then idles calmly into blossoms, birds, and warmer months. It hits peak summer with a photo of a boy on crutches, glowing before a clutch of bright yellow bushes. His barefoot is mysteriously curled, and he appears sharp against the backdrop’s gauzy bokeh (Halpern uses a Pentax 67, perhaps with an older uncoated lens?). In terms of tonal mood, this feels like the apex of the book. We can linger here for a moment before the photos gradually circle back into darker months, and more snowdrifts. By the end, all seasonal bases have been covered. “The book feels warm and cold to me at the same time,” Halpern says, “which I like.”

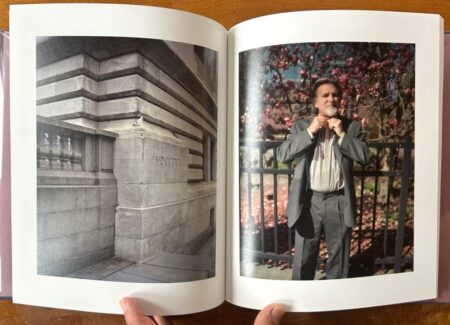

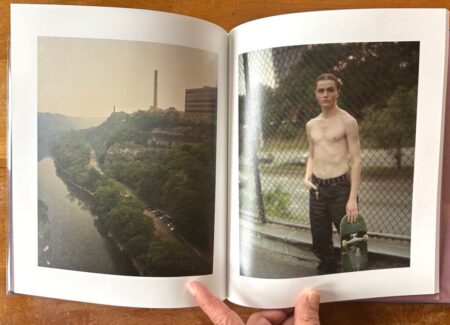

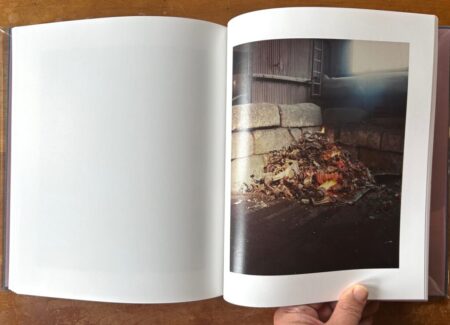

As in Zyzyxx, most photos focus on proximal scenes, captured within a few meters of the camera. A broad overview of cliffs by a river offers a wider glimpse of local geography, but it’s just a brief respite. Most of the book hems the reader into tight city spaces. There’s no hint of nearby Niagara Falls, Lake Eerie, the border, or anything else beyond the immediate neighborhood. Nevertheless the people he encounters in Buffalo might be loosely categorized as outsiders. One boy holds a bandaid to his cheek. Another hovers over his BMX bike. A tattooed man in a daze has his shirt off. A catcher in muddy baseball gear feels out of season and out of place. All seem disjointed in some small way, but that’s just a first impression. Without captions we don’t know who these people are how Halpern found them. We only feel something slightly off kilter about their portraits. Perhaps it is a version of Buffalo’s “Wide Right” curse?

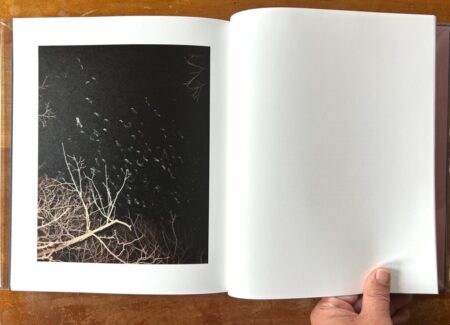

King, Queen, Knave feels like a natural extension of Halpern’s visual style. He has favored vertical frames in all of his previous books, and that’s the the case here too. Every photo is a vertical, lending the book a slightly tipsy quality. The same was true of its close cousin Zyzyxx, and both books cover similar material to boot, e.g. birds, fire, board games, discolored hair, decayed structures, and white animals. These might be unconscious visual triggers for Halpern, private Moby Dicks kept in mind while hunting pictures.

The fact that Halpern can shoot Buffalo with the same dispassionate command that he shoots California or Nebraska is impressive, but also disconcerting. A few of the people depicted in King, Queen, Knave are close friends, and some of the locations are old childhood haunts. But he keeps this information from the viewer, lest it affect the book’s pure photographic impact. We get a chance to revisit only one character in depth, and it’s not even a person. It’s April the deer. Most other buildings, scenes, and people remain cyphers.

In terms of personal intimacy this home town study is a long way from, say, Ed Panar’s Winter Nights Walking (reviewed here), Erinn Springer’s Dormant Season (reviewed here), or Lisa McCord’s Rotan Switch (reviewed here). Those books revisited local connections and relationships, using photography as a sort of cathartic process to work through personal origins and older memories. Perhaps Halpern is doing this too. But if so, he keeps that aspect to himself. “I never wanted to make it specific or personal that way,” Halpern explained to Aperture. “It just never interested me, and I didn’t think that it would be interesting to others to make it too much about me. I guess it’s about a way of seeing. It’s about feeling my way through the city.”

He’s felt his way through all parts of Buffalo, and the book he’s created is a lasting tribute to the city. Come next playoff season, it might even be a salve to locals. Not that they are the primary target audience. King, Queen, Knave should appeal more to the fine art photo crowd. The book’s editing, design, and production are top notch. But it’s Halpern’s disquieting photos which carry the weight, as they should. It’s a pleasure to witness a strong photographer at the peak of his powers, shooting a subject he knows well. “I’ve always found Buffalo kind of magical,” he explained to Aperture, “which I realize to some people might sound like a ridiculous statement.” Browsing these photos, it doesn’t seem ridiculous at all.

Collector’s POV: Gregory Halpern is represented by Galerie Loock in Berlin (here) and Huxley-Parlour in London (here). Halpern’s work has little secondary market history, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.