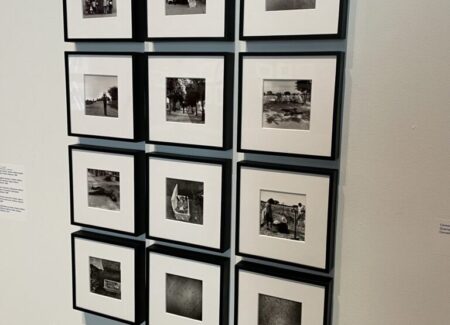

JTF (just the facts): A retrospective exhibition, consisting of more than 150 black-and-white photographs, framed and matted, and hung against white, red, and blue walls in a series of rooms on the second floor of the museum. The exhibit was drawn from the collection of the Fundación MAPFRE, and curated by Carlos Gollonet. (Installation shots below.)

The following works have been included in the show:

Self-Portraits

- 6 gelatin silver prints, 1979, 1989, 1991, 1993, 1996, 2006

The Seri: Those Who Live in the Sand

- 15 gelatin silver prints, 1979

Juchitán

- 18 gelatin silver prints, 1979, 1980, 1984, 1986, 1987, 1988, 1990

Other Borders

- 11 gelatin silver prints, 1974, 1977 1982, 1986, 1991, 1999

Landscapes and Objects

- 28 gelatin silver prints, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2010, 2013

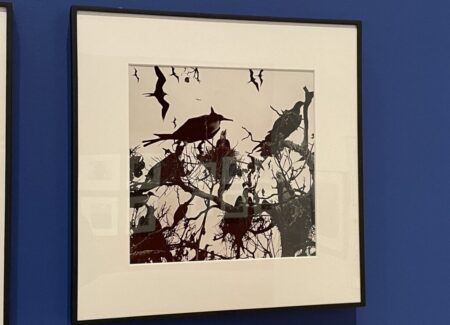

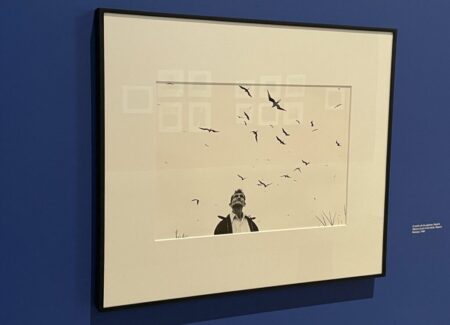

(Birds)

- 8 gelatin silver prints, 1969, 1978, 1984, 1998, 2005, 2007

Frida’s Bathroom

- 11 gelatin silver prints, 2006

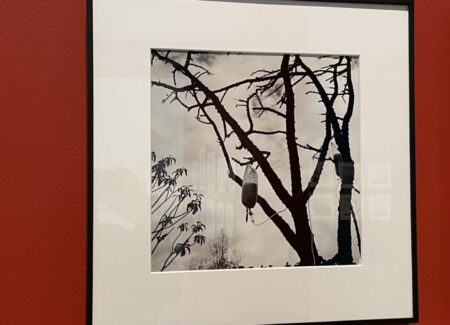

The Botanical Garden

- 13 gelatin silver prints, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2002

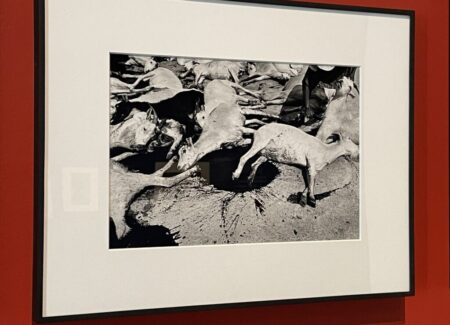

In the Name of the Father

- 10 gelatin silver prints, 1992

(Other Projects)

- 5 gelatin silver prints, 1974, 1980, 1984, 1990

- 12 gelatin silver prints, 1978

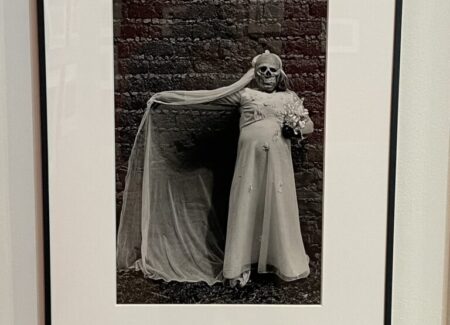

Mexico: Rituals and Celebrations of Death

- 16 gelatin silver prints, 1973, 1975, 1976, 1979, 1983, 1984, 1990, 1994, 1995, 1998, 1999, 2000

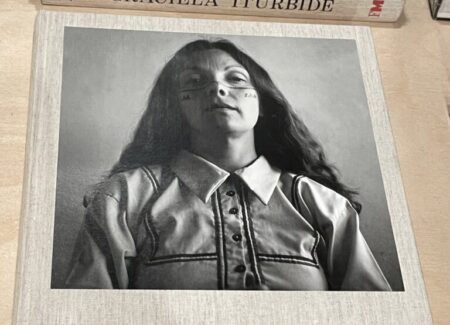

A catalog of the exhibition has been published by the Fundación MAPFRE (here) and Editorial RM (here). Hardcover, 8.6 x 9.8 inches, 292 pages, with 200 image reproductions. Includes texts by Marta Dahó, Juan Villoro, and Carlos Martín García. Design by Fernando López Cobos. (Cover shot below.)

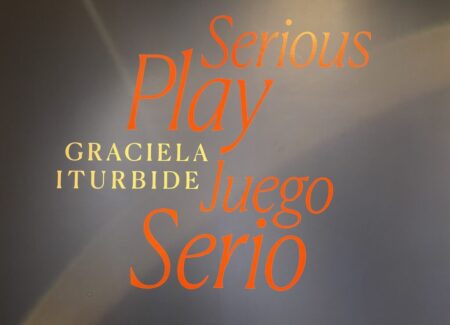

Comments/Context: Now in her early eighties, the Mexican photographer Graciela Iturbide has in the past decade or two successfully consolidated her place in the history of the medium. Her 2019 retrospective at the MFA Boston (reviewed here), which also travelled to Minneapolis and Washington, D.C., built on institutional momentum that had started to coalesce more actively with her 2008 Hasselblad Foundation award and a 2011 retrospective at Les Rencontres d’Arles. This smartly edited exhibition at the ICP, drawn from the collection of the Fundación MAPFRE and spanning five decades of work, is her first retrospective in New York City, and checks off yet another box on her life list of artistic achievements and milestones.

What has become curatorially clear in recent years is that Iturbide provides a critical link between 20th century Mexican Modernist master photographers like Manuel Álvarez Bravo (who she traveled and studied with in the early 1970s) and the contemporary Mexican photographers who have established themselves in the past few decades. She’s an integral part of the connective tissue that knits the history of Mexican photography together, both stylistically and in terms of subject matter focus, particularly in the consistency of her work across the 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, and beyond. Her compassionate interest in the lives of rural indigenous communities across Mexico and in the traditions of those places and peoples, in the roles of women and other overlooked communities, and in the interactions of Mexican culture and the land have influenced an entire generation of photographers who have followed in her footsteps, and so to connect the sweep of historical dots, we need to more fully understand Iturbide’s own artistic arc.

This exhibit has been thoughtfully structured to match the architecture of the ICP, creating subsets and groups of work that fill single walls, each one given enough room (roughly 10 to 20 images) to succinctly present the given material. This organization leads to a calm, ordered, loosely chronological progression, with projects and themes introduced, explored, and completed in succession, breaking up Iturbide’s entire career into more easily digestible chunks.

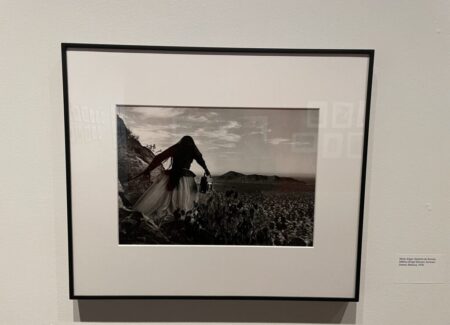

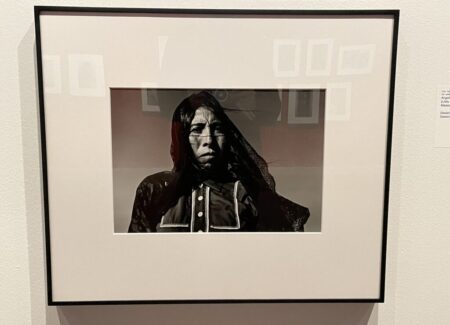

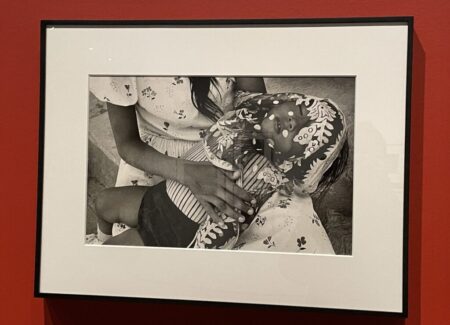

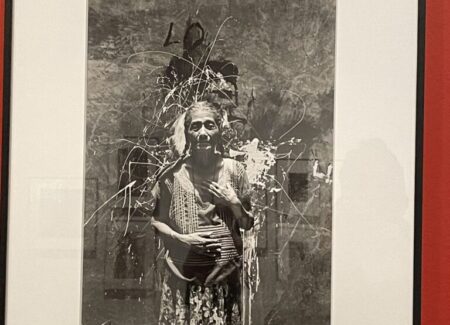

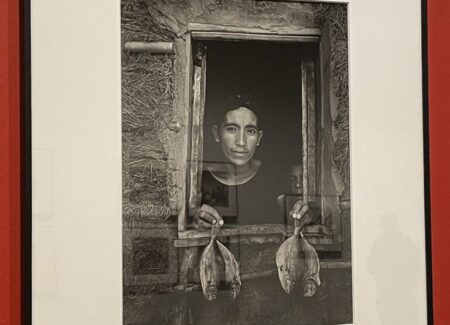

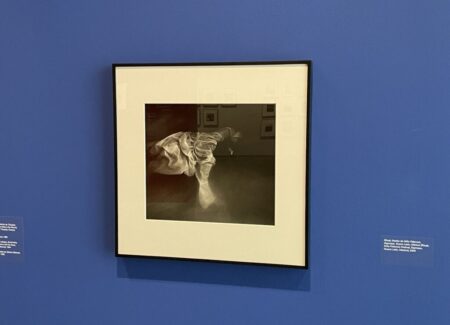

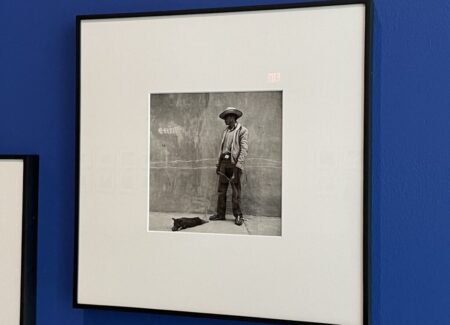

Two powerhouse projects from early in Iturbide’s career fill two sides of the first large room, essentially putting them in dialogue with each other. Her 1979 images of the Seri people from the Sonora desert region (along the US/Mexico border) are mostly portraits, with young faces isolated against the big sky and more fuller bodies (in traditional dresses and headscarves as well as more modern fashions), set against the backdrop of the dusty cactus-strewn landscape.”Mujer Ángel” is perhaps the most famous photograph from this project, the dark silhouetted form of a woman carrying a radio seeming to lift off from the scrubby desert, her flowing hair and long skirt giving her a ghostly magical quality. Iturbide followed these images (through into the mid 1980s) with a project on the Juchitán people of Oaxaca, a matriarchal indigenous society part of the Zapotec culture. Again, her pictures center in on attentive portraits, with a subtle undercurrent of feminism – photographs of women, girls, and elders in various traditional roles and combinations, and of muxes, nonbinary individuals who participate in the female-driven society. Many of these portraits are rich in animalistic symbolism and uncanny ties to the natural world, including the iconic “Nuestra Señora de Las Iguanas”, a woman seen from below with a crown of iguanas atop her head.

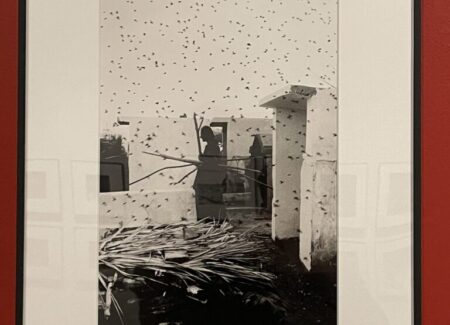

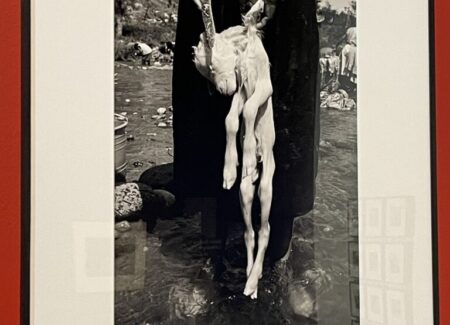

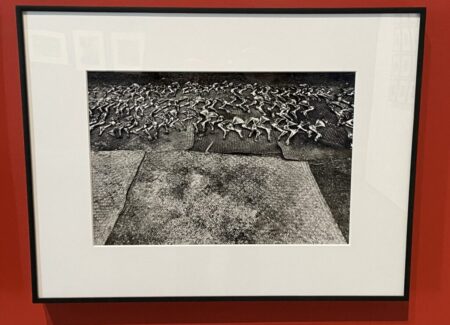

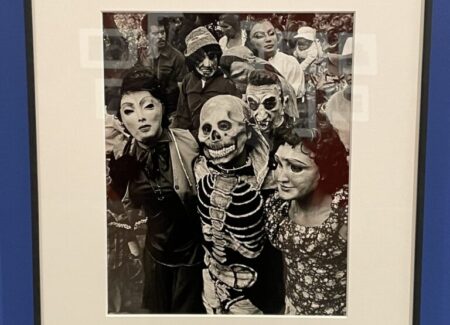

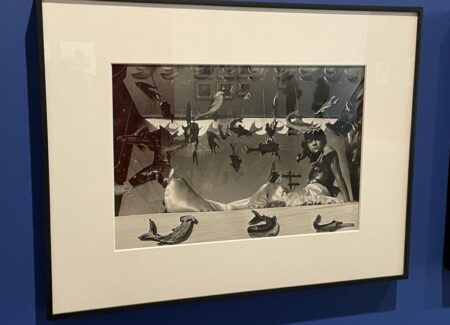

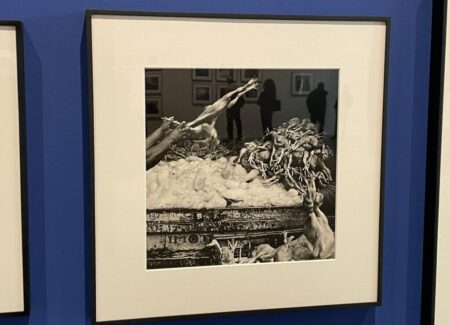

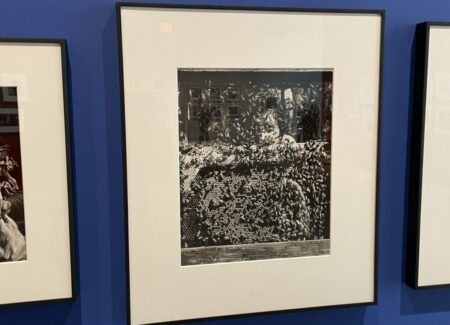

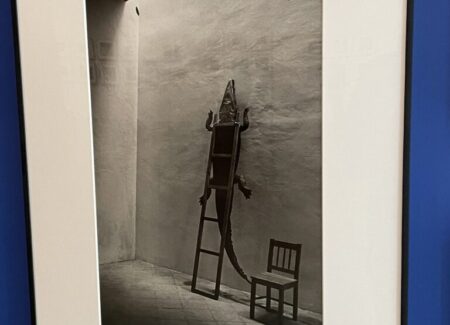

During these same years (through the 1970s and 1980s), Iturbide was also working outside a strictly project based approach, making images in towns and villages all over Mexico, particularly during market days, festivals, celebrations, and religious holidays. These pictures are gathered on a long thematic wall, mixing Catholic and indigenous rituals, as well as stylized images of death, featuring skeletons, skulls, and various animal carcasses. These are subjects that have been documented by countless Mexican photographers before, but Iturbide makes them her own, finding an undercurrent of the quietly surreal in the everyday, where a river baptism looks like a floating body, plastic sharks hover around a mermaid, a swarm of hive bees covers a face, and a lineup of severed hooves sits on a kitchen table. Iturbide went on to dig deeper into these ideas in a 1992 project documenting the ritual sacrifice of goats in the Mixtec mountains of Oaxaca. Not only do these photographs capture the carefully systematic slaughter of the animals, they do so with a keen eye for contrasts of light and dark and for the abstract elements of formal composition; again and again in this project, Iturbide turns the gruesomeness of death into something elegantly seen, from lineups of bones to pools and spurts of blood.

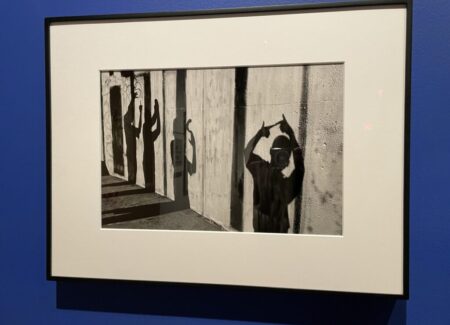

As the retrospective progresses, it becomes somewhat looser, jumping from project and project and theme to theme with less stepwise rigidity. One wall features images of swarms of birds, with psychologically spooky silhouettes darkening the skies and the tree tops like Masahisa Fukase’s ravens. Another spends time at a botanical garden in Oaxaca, paying close attention to trees and plants treated like patients, with hanging fluid bags, supporting ropes, wooden scaffolding, and other treatments, Iturbide’s images filled with formal precision and structural refinement. More recently (in 2006), she turned her attention to the bathroom at Frida Kahlo’s house, creating haunting pared down studies of the tile, the tub, and some of the artist’s prosthetics and braces. And still other collections of imagery probe her self portraits over the years, some nearly bisected dark landscapes, and some architectural studies interested in the found geometries and textural properties of walls, each effort infused with a hint of the hypnotic or the surreal.

While not every project or theme in this survey is entirely memorable, the show does a successful job of educating us on why Iturbide is durably important. The best of her works celebrate a sense of what it means to be Mexican (or human), with an observational directness that is filled with clarity and authenticity and a poetic grace that never feels syrupy. As seen here, her career is deeper than just a few great images, and there are lesser known works on view that have the power to surprise, confront, and photographically delight all in the same frame. For those who can only place “Our Lady of the Iguanas”, there is a wealth of discovery waiting.

Collector’s POV: Since this is a museum exhibition, there are of course no posted prices. Graciela Iturbide is represented by Throckmorton Fine Art in New York (here), ROSEGALLERY in Santa Monica (here), Peter Fetterman Gallery in Santa Monica (here), and Taka Ishii Gallery in Tokyo (here), among others. In the past decade, Iturbide’s work has only been intermittently available in the secondary markets, with recent prices ranging between roughly $1000 and $15000.