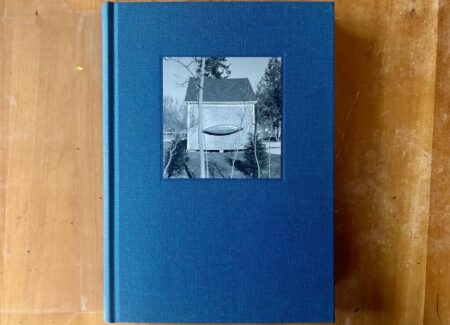

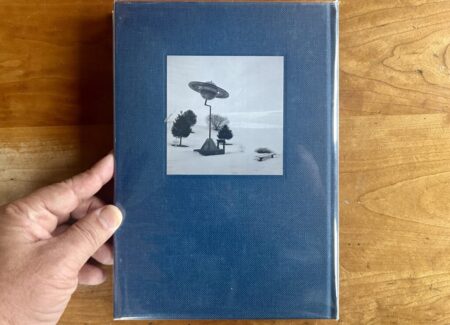

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2025 by The Ice Plant (here). Clothbound hardback with tipped in front and back cover photos, 17 x 24 cm, 192 pages, with 119 duotone photographs. (Cover and spread shots below.)

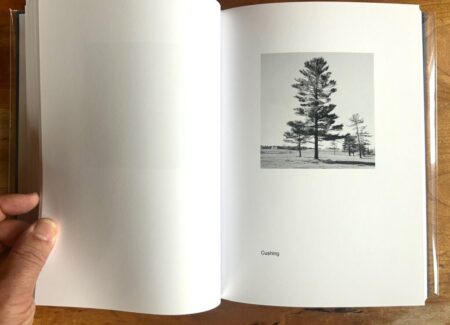

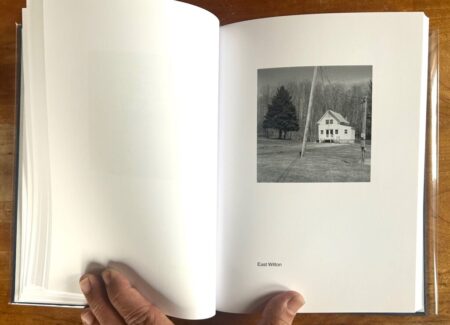

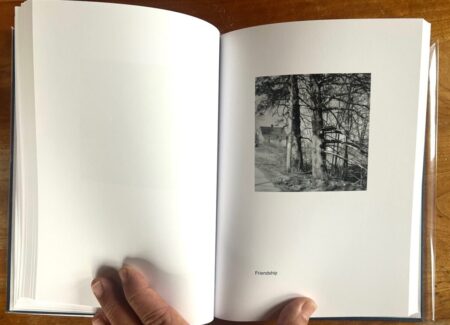

Comments/Context: Gerry Johansson will celebrate his 80th birthday in May. Much of the Swedish photographer’s life to date has been occupied with visualizations of one type or another. In his early years that included graphic design and publishing, but since middle age photography has been his primary focus. He likes to explore quiet areas on foot, capturing depopulated social landscapes on black and white film. In recent decades this propensity has clustered tightly around a signature style of square format formalism. Send Johansson and his trusty Rollei off to any corner of the globe and he becomes a photo-conversion machine. The world feeds raw material into one end and out the other comes a series of four inch squares, each one a carefully composed monochrome frame.

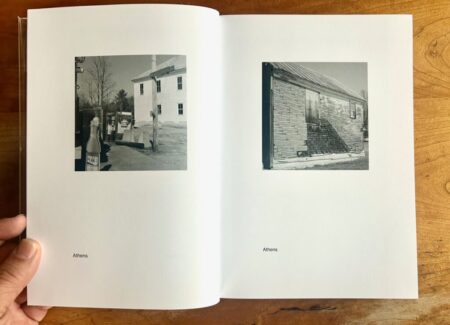

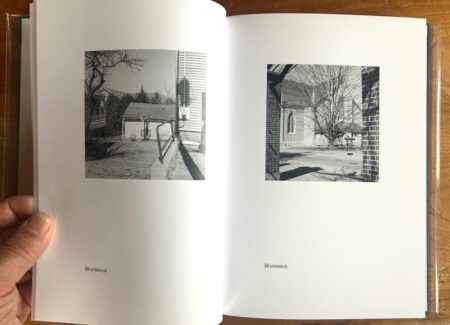

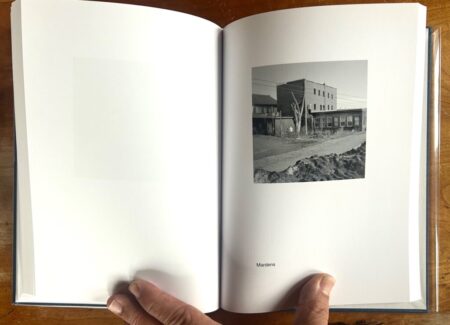

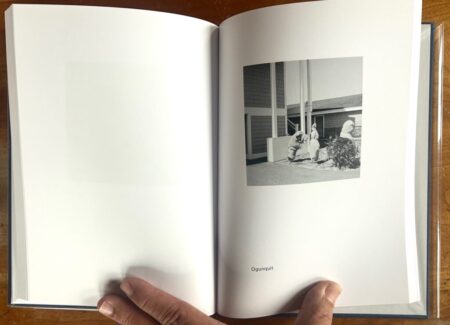

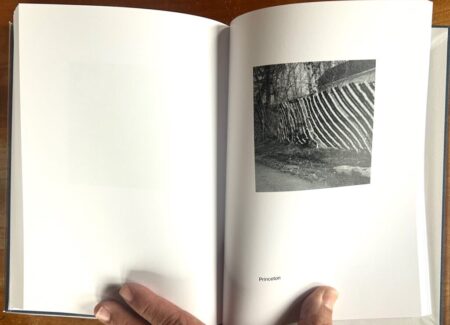

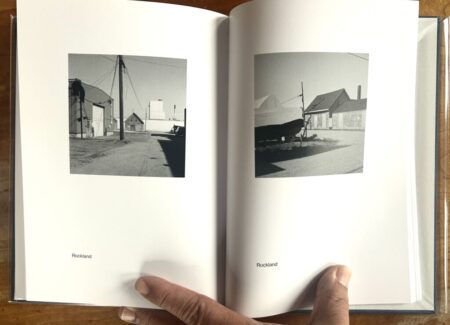

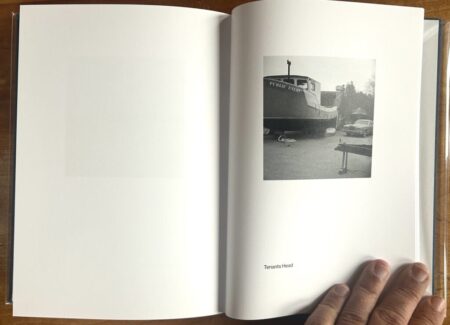

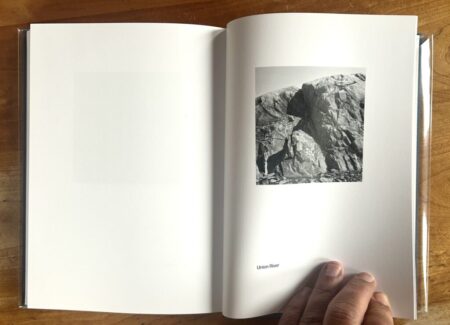

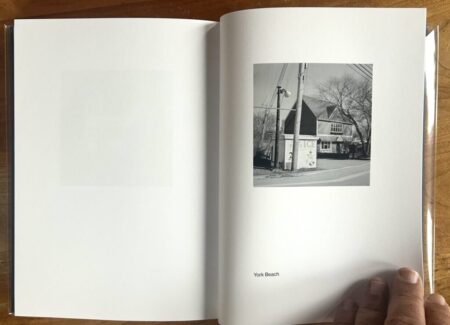

After exposure comes the edit. Johansson typically captions his pictures by place name, then orders them alphabetically into region-specific photobooks. “Every picture is a new story,” as he once explained his sequencing in an interview, “and to emphasize that there was no edited story line they’re presented in alphabetical order.”

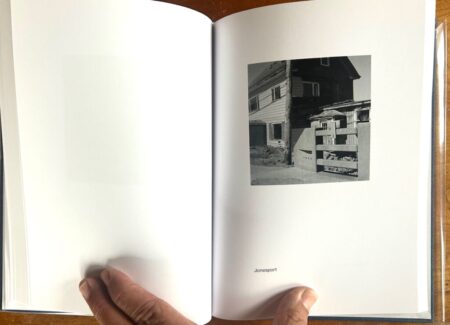

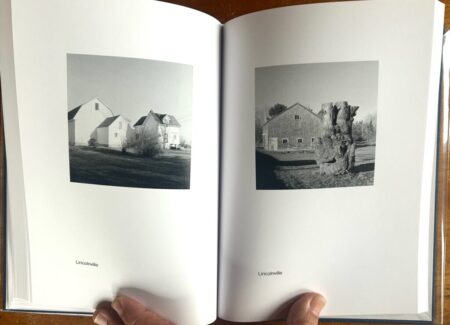

A sampling of Johansson’s recent titles reads like a geography quiz: Sverige, Kvidinge, Pontiac, Deutschland, Spanish Summer, American Winter, Borås, Antarktis, Halland (reviewed here), and so on. Hundreds of photographs are typically presented in each book, one or two per spread, top-weighted on the page, with place names below. Most monographs (with the exception of Tokyo, reviewed here, and a few others) adopt the same dimensions, materials, layout, and Helvetica typeface.

When you consider Johansson’s photography and bookmaking together, his output is a beacon of consistency. No cropping, no motion, no color, no artist statement, no design experiments, digital interventions, or frills of any type. Just a series of identically sized straight photographs, channeled into a monograph with encyclopedic detachment. Some might discount his cool Scandinavian style as reserved and predictable. The counter argument is that Johansson communicates in a strong and distinctive voice. His photobooks are identifiable at a glance, and they’ve staked out a photographic style—which might be branded a “Johanssonian democracy”—which is his alone.

The latest region to receive Johansson’s attention is Maine. He spent the better part of 2023 exploring the Pine Tree State, scouring coast, rocks, lakes, mountains, industry, and solemn townscapes. The resulting photobook Maine is his first publishing venture with The Ice Plant, but you’d never guess that from the design. Aside from the blue cover, Maine’s dimensions, materials, design, and typeface are virtually identical to his previous monographs.

Why Maine? Johansson’s crush has been simmering for a while, sparked long ago by an interest in Paul Strand. “I saw his Blind Woman as a teenager and admired his work,” he explained to me once in an interview, “but then he was ‘lost’ for me during many years, actually after seeing Time in New England which I didn’t like at all at that time. But he has gradually come back to me.”

So the primary motivations were homage and re-engagement. In the hope of better appreciating Strand, Johansson decided to see New England for himself. Maine’s colorful place names probably didn’t hurt the cause. The book’s captions chart a free verse poem of locations from Athens to Bath, Belfast, Industry, Lubec, Mexico, Owl’s Head, Purgatory, and beyond. There’s even a photo from Skowhegan, a sleepy town on the Kennebec River which I’ve visited and photographed every summer for many years (my in-laws live nearby on Wesserunsett Lake). Short term interlopers like myself may never be accepted as true Mainers, but I’ve spent enough time in the state to recognize the occasional misnomered location (Mardens is a discount store where my sons shop, not a town. And Norridgewock is spelled with an “I” not an “E”).

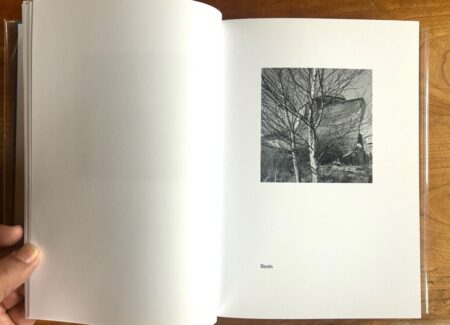

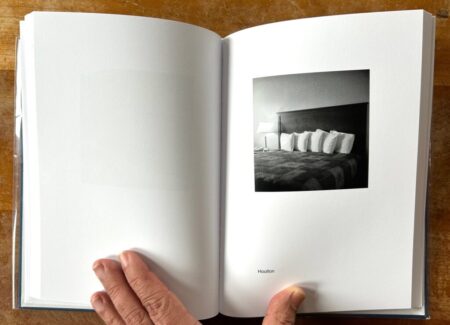

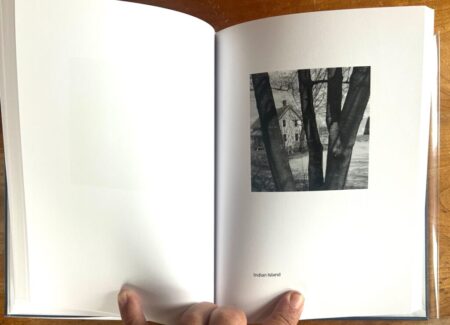

But Maine isn’t merely a book of place names. Johansson’s photographs are the main attraction. True to past form, he churns them out here with the efficiency of a lumber mill. Whether sifting deep woods or residential streets, his curiosity and vision are unerring. The use of monochrome film helps him reduce three dimensional objects to their essential forms, and he weaves layers, edges, and tonalities with Friedlanderish wit. In the town of Caribou, for example, he foregrounds a distant apartment complex with a nearby explosion of unpruned branches. The composition is so busy it takes a moment to dissect. Then it resolves beyond doubt. He pulls the same trick in Mexico, juxtaposing a pale factory with a wall of broken trees. Exploring upstate in Houlton, he visual clay to mold without even leaving his hotel room. A row of white pillows on a dark bed is stark and well balanced. If I didn’t know better, I’d suspect it was consciously arranged. But the book’s implicit agreement is clear: Johansson does not alter subject matter.

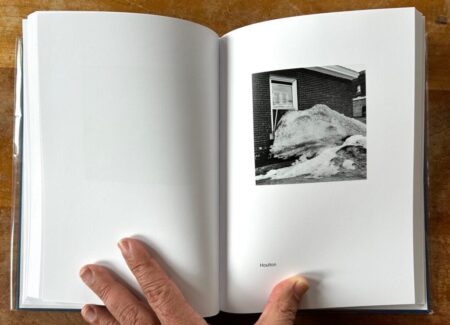

Perhaps he found the snowbank photo close to the pillows? It’s from Houlton too, but this scene was shot outside a brick building. The grimy pile takes up most of the frame, hanging on the verge of Abstract Expressionism. But that might be my imagination playing tricks. On second thought, no, it’s just an old snow pile and nothing else. Maine has plenty more of these. Just flip the pages to see others. Johansson has described himself as a winter photographer, and the majority of these photos document the cold season. Whiteness is a looming presence in the book, along with bare limbs and wan skies. Throw in a few church steeples and Paul Strand might feel at home here.

Speaking of Strand, a few things. It’s worth noting that he named his classic 1950 monograph Time In New England. Even if its photos were mostly static, the title deliberately put them on the clock. Johansson’s, on the other hand, feel rather timeless. He generally avoids photographing people, clothing, cars, advertising, or other easily dated material. These photos of Maine might be from 2023 or 1973. Their age is hard to pin down, and that ambiguity keeps them from dissolving too quickly in the brain.

Beyond timing, Strand’s fundamental aim seems different than Johansson’s. Strand wanted to present strong photographs of course. But Time In New England also includes numerous text passages. When words and pictures are taken together, the book is something of a regional exposé. Not so for Johansson. Maine feels less like a cultural study than an exercise in seeing. Woods, structures, clouds, and snow combine in endlessly dynamic ways. All good, but the view is generalized. Without captions, one might mistake his Maine photos for Sweden or Kansas.

That uniformity is a tribute to Johansson’s steady vision. He may be a photographer’s photographer, but his pictures don’t tell me much about Maine as Maine. What’s it like to stink of sawdust, machine grease, or lobster guts? What about the state’s Quebecois culture, sugar camps, moose hunting, or pride as a geographic outlpost? Maine’s license plates may say “Vacationland” but that label only applies to the coastal area east of Route 1. Venture fifty miles inland and you’re in Trump country. Ironically Johansson did so many times, but his photos come to us without any political trace.

That’s an observation about Maine, not a complaint. In the contemporary photo world of ever shifting conceits, identities, techniques, and mediations, I admire a photographer who wanders around taking pictures just for the sake of pictures. “The pleasure of good photographs,” said Lee Friedlander, “is the pleasure of good photographs.” This book is a treasure chest of sharply composed observations, and perhaps it needn’t be anything more. Johansson is almost 80 and still going strong. If he keeps making pictures at his current rate, he may yet become a role model.

Collector’s POV: Gerry Johansson is represented by Dorothée Nilsson Gallery in Berlin (here) and Large Glass Gallery in London (here). His work has only been sporadically available in the secondary markets in the past decade, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.