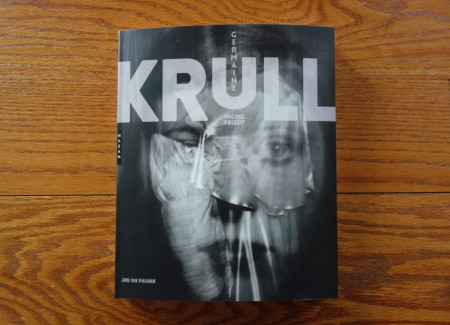

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2015 by Jeu de Paume/Hazan (here) in conjunction with a retrospective exhibition at the Jeu de Paume (here, June 2, 2015 to September 27, 2015). Softcover, 264 pages, with 270 black and white reproductions. Includes multiple essays by curator Michel Frizot, as well as a timeline and bibliography. In English and French versions.(Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: While the definition of a photobook has broadened to encompass all kinds of publications with photographs in recent years, the exhibition catalog/retrospective monograph remains a valuable specialized genre, largely different in both purpose and style than the typical single artist, single body of work photobook. As such, catalogs need to be judged by a different set of criteria, taking into account not only the merits of the photographs included and the construction of the volume itself, but the clarity of the organization, the thoughtfulness and originality of the historical and artistic analysis (as embodied in the essays), the quality, editing, and comprehensiveness of the image reproductions, and the book’s overall usefulness as a work of durable insight and reference. In simple terms, I think there is a kind of “shelf” test for catalogs – if you already have a shelf of books on this photographer, does this new summation add to the overall aggregate understanding of his/her work and therefore earn a place in the library?

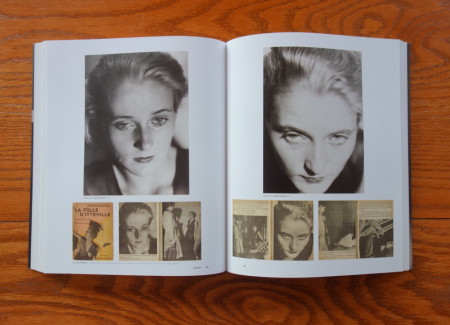

In the case of the 20th century French photographer Germaine Krull, the shelf of existing reference books about her life and work is remarkably small, with virtually no important additions since the publication of Kim Sichel’s Germaine Krull: Photographer of Modernity in 1999 (MIT Press). But even if there had been more historical work done on Krull in the past, Michel Frizot’s comprehensive analysis would certainly merit further study. It largely tackles the puzzles of Krull with fresh eyes, with a particular emphasis on how she expanded the influence of her photographs via photobooks, magazines, and other publications. Organized chronologically for the most part and using subject matter-driven themes (nudes, cars, hands, etc.) as another vector of analysis, it carves her artistic production into many discrete pieces, allowing us to see each one with stand alone clarity as he meticulously chronicles both the highlights and the overlooked alleys of her career.

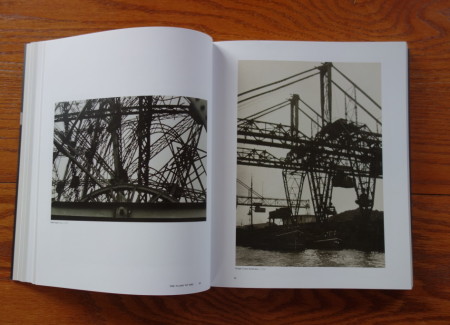

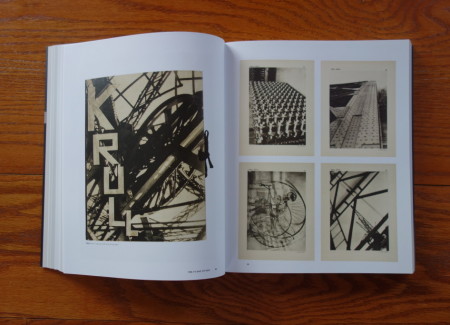

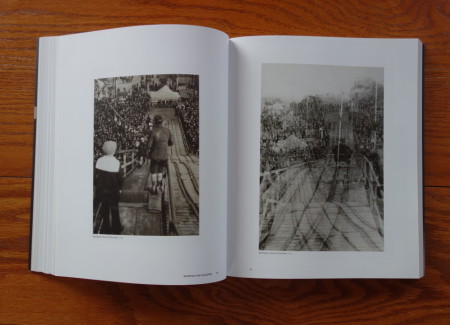

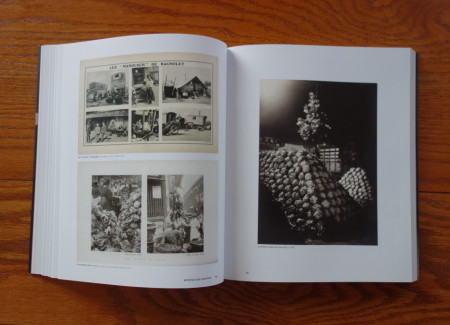

Krull’s deservedly iconic 1928 photobook/portfolio Métal is likely her best known body of work, but Frizot doesn’t over-bias his analysis toward featuring it. Her sharply Modernist views of Rotterdam’s iron bridges, cranes, and steel factories, the Eiffel Tower, and other industrial structures from Marseille and elsewhere rely on the steep angles and geometric patterns that would become the hallmark of the New Vision, her rigorously inventive formal compositions embodying a kind of bold photographic radicalism. But rather than spend time explicating skyward crops and up close details, Frizot instead follows the pictures as they fanned out into magazines like VU, Variétés, and Jazz (with images of the original spreads included in the catalog), chasing the influence of Krull’s innovative machine aesthetic as it was absorbed into the mainstream.

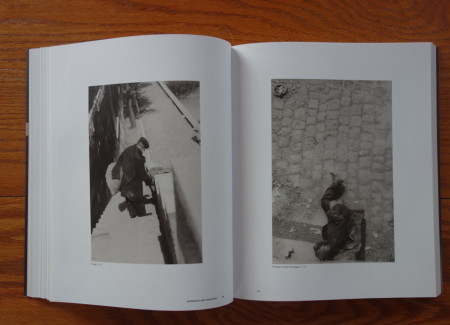

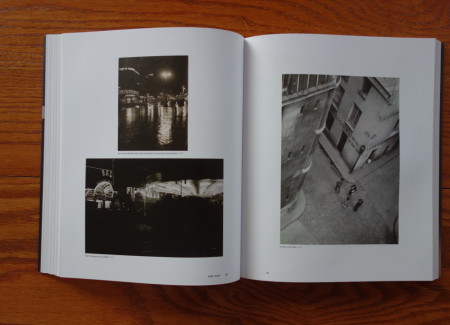

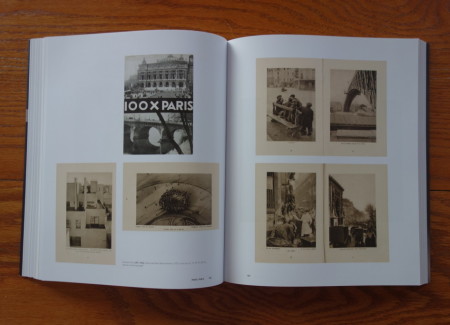

Krull’s subsequent work for VU (where she collaborated with André Kertész and Eli Lotar) in the years between 1928 and 1931 found her reveling in the margins of Paris, making images of tramps, funfairs, markets, and dancehalls as illustrations for stories in the magazine. Krull seemed particularly comfortable in this space merging creative and commercial work, where avant-garde double exposures and advertising commissions provided two intertwined artistic paths. Many of Krull’s pictures of Paris were gathered into the photobook 100 x Paris, where her views of the city seem to spin in all directions, and others (including night scenes and views of department stores) multiplied out into a handful of additional illustrated books by other authors celebrating the modernity of Paris. Once again, Frizot uses these many publications as the anchor for a wider investigation of the driving forces behind Krull’s work.

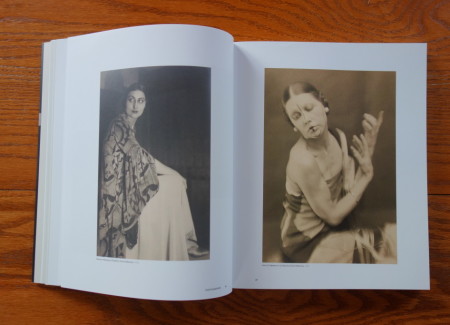

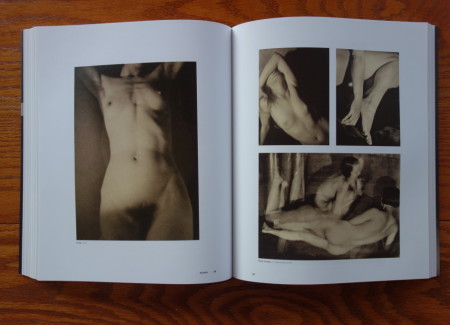

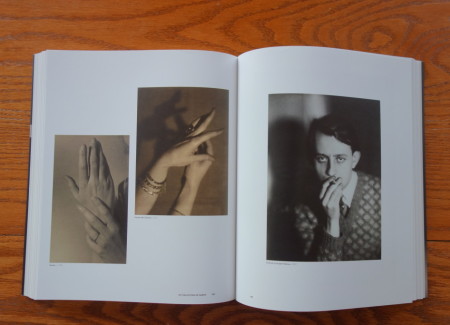

A third line of Krull’s thinking turned more inward, to female nudes in two parts, once in the early stages of her career (roughly 1924), and then again half a dozen years later (which became the photobook Études de Nu). Here again, we find the photographer consciously pushing at established aesthetics. While her earliest nudes emerge from a Pictorialist approach, her nude with masks, her paired lesbian studies, and even her clothed portraits of Sonia Delaunay and her textile creations all point toward liberated risk taking. When she returned to the subject some years later, she moved in much closer, framing the bodies into more innovative and subversive formal studies of line and curve. Both sets of photographs overtly reclaim the female nude from the domain of male photographers, offering a sensibility more comfortable with ambiguity.

While the case for Krull’s inclusion among the key figures of between the wars Modernism has been made before, this retrospective volume certainly adds to the weight of that primary argument – Frizot highlights several superlative bodies of work that are worthy companions of the best photographs of her better known contemporaries and expands our knowledge of her evolving mindset (via her many memoirs and journals). And for photobook fans, Frizot’s analysis shows her to have been an early convert to the power of the printed photographic image and a open-minded adopter of the photobook form as a way to both control the display of her work and reach her audience. In the end, Krull was clearly a strong willed, intuitive, and vibrant personality, and that rebellious spirit came through in the vitality of her photographs. This retrospective catalog does an admirable job of laying out her key contributions, filling in the backstory to yet another powerful female photographer who deserves to be rediscovered.

Collector’s POV: No one gallery manages the available work of Germaine Krull, so collectors will have to search with more persistence among various dealers of vintage photography to find her scarce prints. At auction, her works have recently ranged in price from roughly $2000 to $38000, with multiple image sets fetching sums nearing $45000.