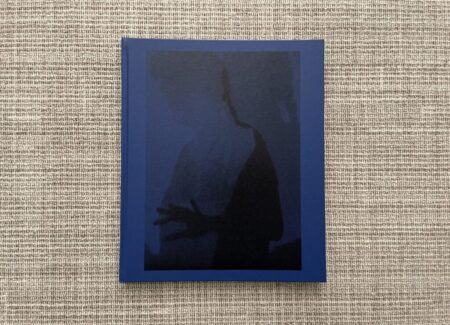

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2025 by Capricious (here). Hardcover, 10.5 x 12.5 inches, 141 pages, with 43 color reproductions and 3 sets of video stills (printed on black paper). Includes essays in English/Spanish by Hilda Lloréns and Elle Pérez, and a caption list. Design by Studio Lin. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: One of the major trends in contemporary photography in the past decade has been the wider photographic investigation of personal diasporic histories, particularly by women. By their very nature as artistic studies of lives that span two (or more) locations, these explorations consistently wrestle with issues of individual identity, dislocation, family, memory, relationships to place and land, and in some cases, a search for what is absent or has been lost. And as it turns out, many of these themes are essentially unseen or invisible (at least to a camera), and so these diasporic photographers have had to be creative in finding ways to visually tell their stories and express their conflicted emotions. This has led to a flourishing of richly resonant conceptual approaches, including exploring the possibilities found in archives and family heirlooms, employing active staging and re-enactment, and using multiple exposures, collage, and other interventions and techniques to evoke an oscillating sense of layering and combination. In many ways, we can equate these photographic searches with a kind of expressive mapping activity, where the artist is trying to locate herself in the world and establish a more durable sense of presence.

The particular diasporic history that lies beneath the work of Genesis Báez is rooted in Puerto Rico. Born in Massachusetts to Puerto Rican migrant parents, Báez has spent her life going back and forth between New England and the Caribbean island (which is both a former Spanish colony and a current US territory). She studied at both MassArt (for her BFA) and Yale (for her MFA), and her first photobook Blue Sun summarizes a bit more than her first decade of artmaking and its efforts to make visible some of the complexities found in her hybrid existence.

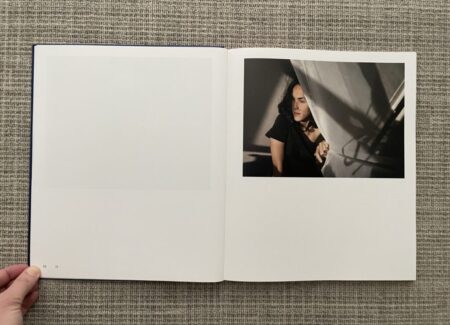

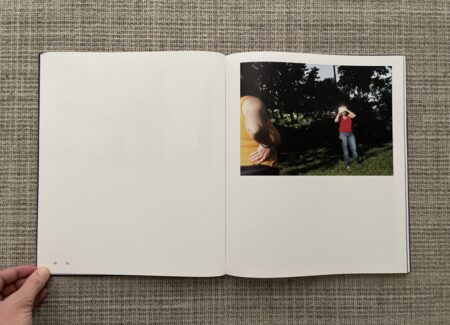

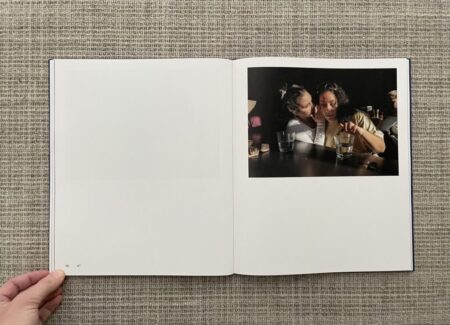

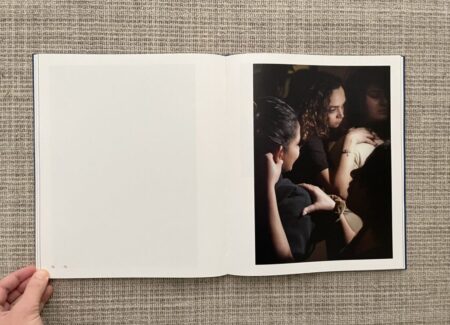

Given her art school training, it’s not entirely surprising that Báez has developed a wide ranging, and often elegant, set of conceptual solutions to the larger challenge of visualizing the invisible in her diasporic reality. A multi-generational line of women and girls (including by my count a grandmother, a mother, at least one aunt, other female relatives, and the artist herself) lies at the center of her thinking, a matriarchal structure of deep family connection (and presence in her life) that Báez has liberally used to structure her pictures. But of course, the links that bind these women together are largely invisible, so Báez has observed, and in some cases engineered, physical ways to represent these important attachments. Several images capture subtle gestures of personal touch, with one woman helping another with a coat, gently touching a forehead to hold back hair, placing a reassuring hand on a shoulder, caressing an ear, and helping to braid hair.

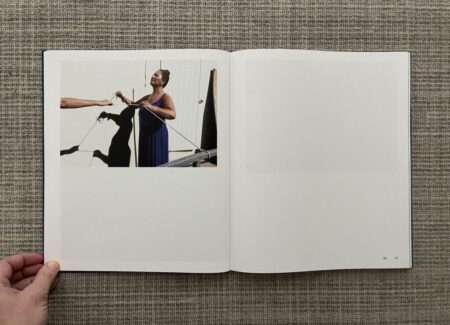

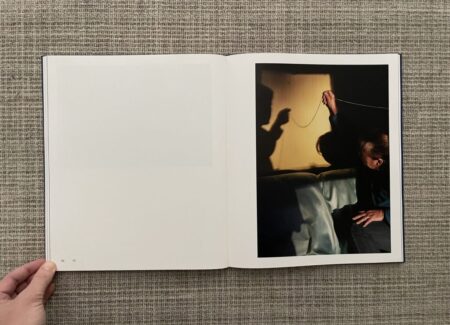

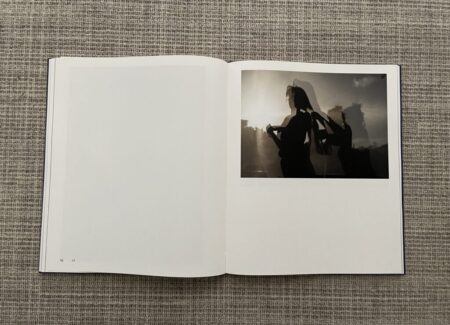

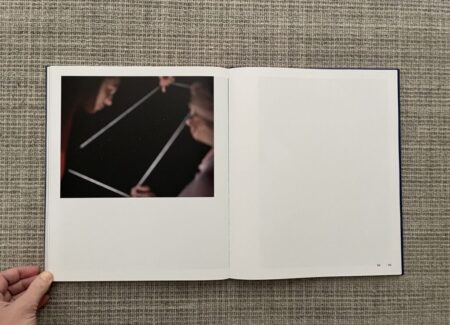

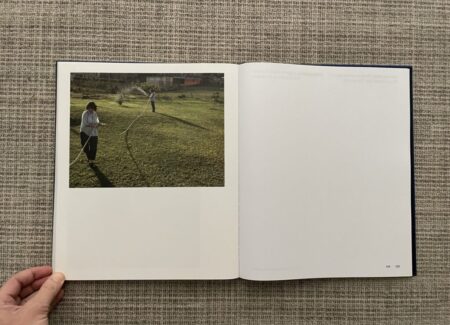

Báez has then gone on to make these relationships more literal, via physical connections of one kind or another. In “Watering Time”, women are connected by the sag of a garden hose; in “Mapping Suns”, a blurred pair uses lines of string to define a rectangular portion of the night sky; in “Crossing Time”, two hands use a thin string to connect, one figure (likely the artist herself) seen only as a silhouette; and in “Pull (The Weight of Two Suns)”, a clothesline is pulled between the hands (and shadows) of two women. In each case, the connection between the various women is drawn in by the lines, like the kinship lines on a family tree.

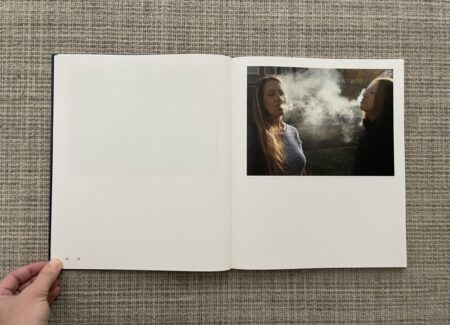

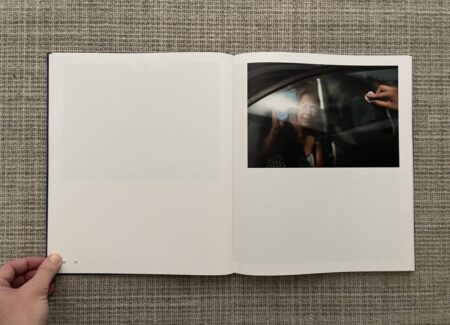

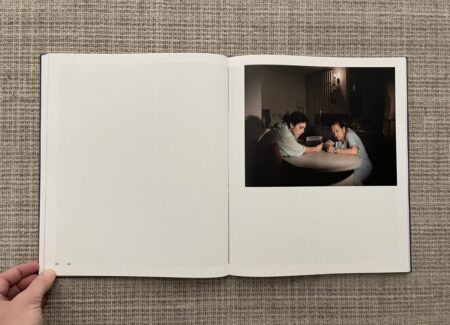

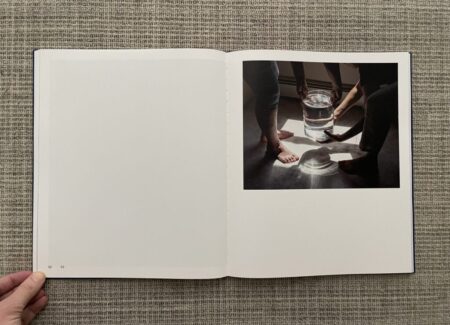

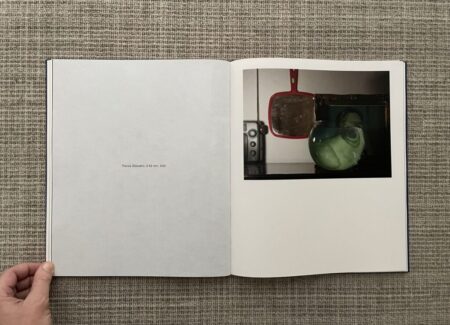

Sound, in the forms of talking, listening, conversation, and other audible atmospherics, is another invisible association between the women in Báez’s life, and she’s cleverly found ways to capture these sound exchanges photographically, even if we can’t hear them ourselves. “Night” documents a quiet conversation in the space underneath a mosquito net, while “Breath” creates a smoky interchange that drifts through the air. “Echo” brings us into a shared moment at the kitchen table listening to the radio, while “The Sound of Circle” actually connects two sounds, the ringing vibration of a finger pulled along the edge of a water glass and an intimate whisper in the ear. And in two other pictures, Báez exchanges a look for something more obviously verbalized, in “Spiral Trace”, with a car window being washed separating two women, and in “Driving to the Water’s Edge”, where the misdirection of a look in the rearview mirror connects eyes in the same frame.

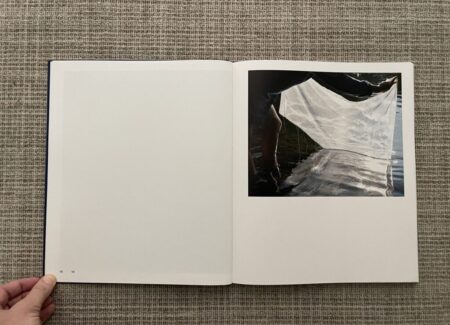

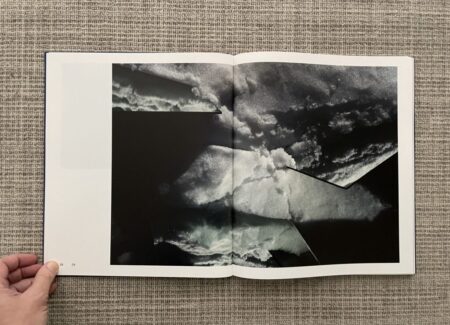

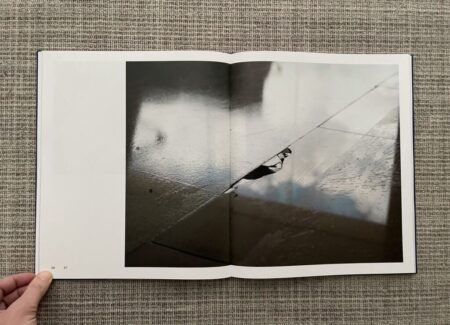

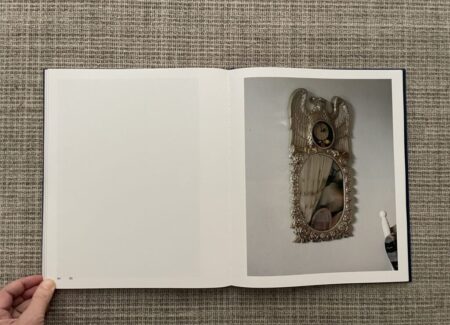

As it turns out, mirrors are a recurring visual motif in Báez’s work, but that last one is really the only one that offers a legible reflection. More often Báez’s mirrors offer blinding flashes and glares, distortions, blurs, and other even less identifiable refractions, making them photographic mechanisms for breaking up space, collaging imagery together, or simply frustrating communication. “My Body as a Portal Between Sky and Earth” is one of the strongest of these images, as it uses two halves of a broken mirror to physically locate Báez. Other images with mirrors capture a sense of uneasy disorientation, the rooms and the objects in them refusing to coalesce, leaving the artist in an in-between state.

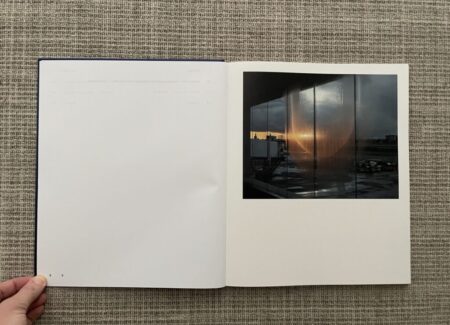

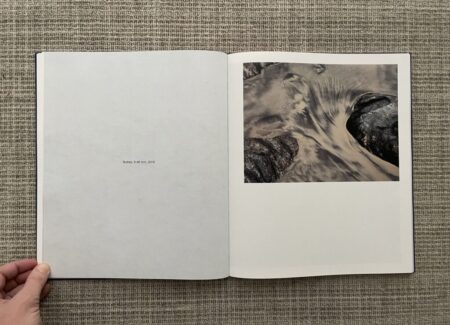

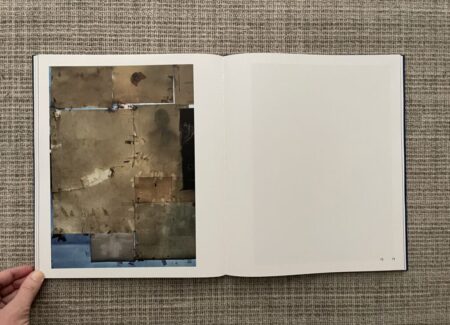

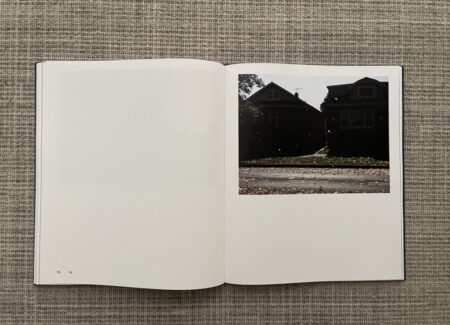

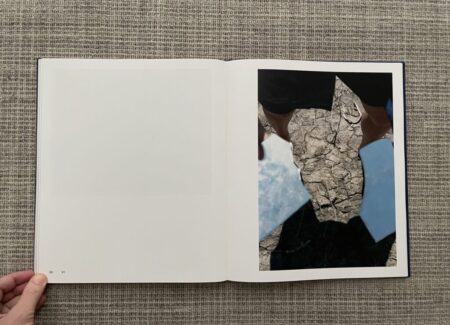

Most of the rest of the images in Blue Sun are sensory exercises of one kind or another, where the picture attentively places us in a specific moment, in one of the artist’s two locations, creating a grounded sense of interiority. The invisible movement of air takes shape as a breath of wind carrying tumbling leaves across an autumn street scene, a standing fan creating a breeze in a sewing workroom, and the billowing of curtains and a mosquito net from gusts coming in through the window. Water (and its presence in many forms) is another common motif, seen in many forms, including the humid condensation on an airport window, a full fishbowl interrupting our view of a family photo, the muddy cloudiness of a river or pond, some frothy waves at a scraggly beach, and a full jar of water held by pairs of hands. Báez then moves in even closer, creating textual abstractions from all-over observations of sand, rock, crackled paint, dirt, concrete, and snow, pulling us back and forth between indeterminate locations north and south.

As a photobook object, Blue Sun is resolutely divided, with all of the text (including the spine text, the title page, the contents page, the essays, the captions, and even the artist acknowledgements) doubled with equal weight in Spanish and English. It’s a relatively large book, with a halftone image of layered silhouettes (also doubled) on the front cover. Inside, the photographs are given plenty of space to breathe, with only one image per spread, most often set on one side or the other. The resulting flow feels deliberate and balanced, with a nuanced back and forth rhythm created by the sequencing. All of these design decisions support the larger themes Báez is exploring, making the whole feel integrated and congruent.

With this solid first monograph, Báez has confidently set down an initial marker, making an understated but effective argument for her inclusion in the larger diasporic dialogue taking place right now. Seen as body of work, Blue Sun feels thoughtfully considered, emotionally poised, and compositionally meticulous, the work of an emerging photographer who has begun to trust her own voice. More than a few of these images seem ready for institutional support, particularly in the context of a growing cohort of female photographers remixing previously discrete photographic strategies into a new kind of exploration of fragmented self. I’m particularly curious about how Báez can build on this early momentum, and use the inherent tensions (and joys) of her contemporary Puerto Rican American experience to teach us something about who we are today.

Collector’s POV: Genesis Báez does not appear to have consistent gallery representation at this time – but given the quality of this work, that will likely change soon. As a result, for the moment, interested collectors should likely follow up directly with the artist via her website (linked in the sidebar).