JTF (just the facts): A total of 26 color photographs, framed in white and unmatted, and hung against white walls in the main gallery space. All of the works are pigment prints with paint on non-woven paper, made in 2024 or 2025. Each is sized roughly 43×53 inches and is unique. (Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: Deciding to make visits to Claude Monet’s famous gardens at Giverny in France, and then to make artworks inspired by those gardens isn’t exactly a new idea. It was of course Monet himself who was first inspired by the house and land there, and who then actively transformed them over decades into the gardens, bridges, outbuildings, and pond that became the resonant source material for his paintings. Countless tourists now flock to the gardens each year, most snapping their own photos of choice views, in the hopes of capturing some of the magic Monet saw and felt there, with more than a few trying to make their own versions of Impressionistic blurs of water lilies and the Japanese bridge in homage to the master.

The problem is of course that it’s very hard not to be trapped into making pale imitations of Monet’s aesthetics – many of the Giverny views and vantage points are now recognizably famous, as are Monet’s nuanced interpretations of them, so to wade into those very same subjects and attempt to artistically make them your own is a very real challenge. The test is whether an artist can actually re-imagine such a place, honoring the sense of nostalgia and respect that exists in working there, but then extending beyond those impulses to create something new. Simply recreating Monet isn’t enough.

François Halard’s show of photographs made at Giverny is titled “Conversations with Claude”, which is a clever way to finesse this issue – a conversation implies some back and forth and some sharing of ideas, even across time. The French photographer has built a distinguished commercial career making expressive images of architecture and interiors, his style often leaning toward the intimate and the atmospheric, particularly when working with Polaroids, which makes his approach a decent match for the many moods and colors of Giverny.

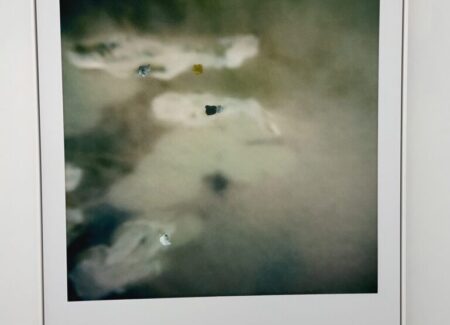

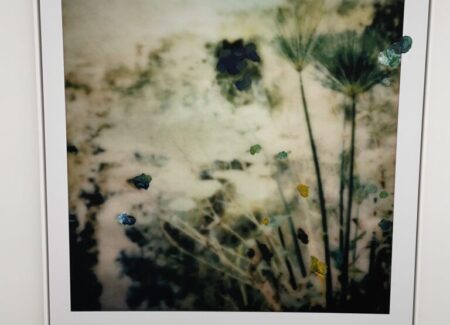

Aside from a few ethereal up close florals, Halard has largely centered his attention on the water lily pond at Giverny, as seen at different times of the day. For the most part, he’s aimed his camera at the surface of the water (cropping out the landscape surroundings), noticing arrangements and groups of floating lily pads, in some cases layered with the distorted reflections and shadows of the nearby sky and trees or interrupted by the wispy greenery found at the pond’s edge. Given the particular color chemistries of the Polaroid process and Halard’s own aesthetic tendencies, it’s not entirely surprising that his resulting photographs would feel soft and pictorial, especially when the sky drifts to twilight and the forms loosen up and flare toward abstraction. Even the darkest blacks and richest blues in his watery palette feel impermanent, their subtleties then punctuated by the many personalities of the floating plants. And Halard is clearly aware of echoes of Japanese art that these scenes evoke, his compositions deliberately sparse and unbalanced, capturing the fleeting ephemerality of this highly controlled but natural world.

Halard is most successful at transporting us into his own aesthetic environment when he moves in tighter and allows the forms and colors to wander – the less literal (and the more expressively abstract), the better. This is particularly true in his sophisticated use of color, with delicate misty greens, seething yellows, washed out whites, dappled blacks, and faded limpid blues becoming their own stories, regardless of the specific subject matter. When the pond is entirely still (which it is most often), the colors match that deep sense of calm; but with a little breeze across the surface, ripples, shimmers, and squiggles emerge, adding to the visual possibilities.

It’s possible to imagine Halard back in his studio, looking over these well-made Polaroids, at once altogether satisfied with what he has captured, but also somewhat underwhelmed by the pictures before him – the flatness of the palette does indeed soften and abstract the views in a seductively expressive way, but it also washes out any sense of sparkle that might have existed in the gardens, leaving the photographs a bit muted and understated as a whole. There’s a fine line between lushly atmospheric and dull, and Halard might have felt the urge to inject some energy and life back into the compositions, if only to make them a bit more unexpected.

He did this by adding a layer of overpainting to his enlarged photographic prints, with dollops of color placed strategically around the compositions to amplify the brightness of the light. In some cases, his splashes of color land right on the lily pads, drawing our attention to them even more and accenting (or modifying) their color stories. In others, the application of paint seems more improvisational, with spots spread and more watery washes and drips adding to the overall atmosphere rather than a literal embellishment. And in a few cases, Halard’s paint wanders outside the edges of the photographic image, bridging outward from that particular moment in time. The most successful overpainting enriches the underlying pictures, giving them a renewed sense of Impressionistic energy and personal touch, like points of light given a small boost of power.

I’ll admit to some initial skepticism about whether Halard could actually find his own unique path through a clichéd subject like Monet’s gardens, but there are a handful of standout works on view here that really do push somewhere fresh but still reverent. While it might be easiest to be quietly dismissive of the obvious decorative qualities of these pictures, when he finds the right key, there are many ethereal harmonies to be found in Halard’s overpainted photographs, especially when that effervescent sparkle hits just right. It’s these jarringly splashy moments that will bring plenty of viewers back for a second, more deliberative look at a subject they think they already know.

Collector’s POV: The works in this show are priced at $26750 each. Halard’s photographs have relatively little secondary market history, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.