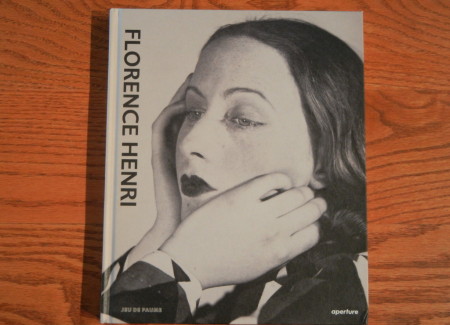

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2015 by Aperture (here) and the Jeu de Paume (here), in conjunction with an exhibition at the museum, running from February 24, 2015 through May 17, 2015 (here). Hardcover, 224 pages, with 180 photographic reproductions. Includes essays by Marta Gili, Cristina Zelich (curator of the exhibition), Susan Kismaric, and Giovanni Battista Martini. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Back a decade ago, even the most knowledgeable participants in the photography community would likely have assumed that the between the wars period of 20th century photography was well understood – the prominent artists, the major pictures, and the general framework and evolution of the aesthetic influences were all widely and thoroughly documented. And yet, with the help of some persistent curators and institutions, this pivotal period in the medium’s history has recently been reopened for further investigation and reinterpretation. At MoMA, the in-depth work surrounding the Thomas Walther collection (exhibition reviewed here) rebalanced the biases against the German and Russian photographers of the times, bringing forward countless names and images that had been marginalized over the years. And in parallel with this activity, the Jeu de Paume has been staging a series of exhibitions highlighting some of the important female photographers working in Europe during those years, digging deeper into the work of Lisette Model, Claude Cahun, Berenice Abbott, Eva Besnyö, Laure Albin Guillot, Kati Horna, Florence Henri, and Germaine Krull (on view now), and reconsidering how these women (who were often overlooked in the accepted art historical narrative) contributed to the experimental momentum of the period. With significant effort, the conventional wisdom has changed, opening up a broader and more inclusive view of what actually occurred between the wars.

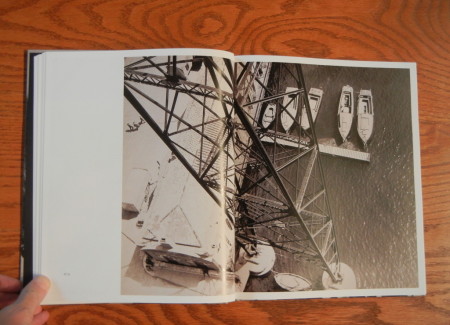

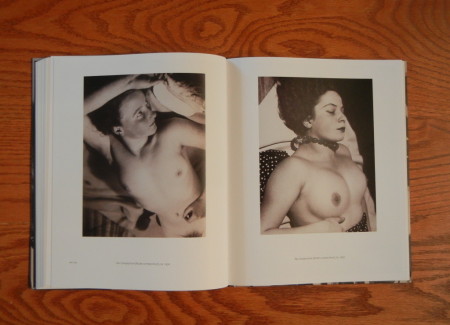

This well researched retrospective catalog of the now closed Florence Henri exhibition certainly fills in many of the gaps in her story (she will be virtually unknown by some to be sure), and makes a compelling case that during her most active period of innovation (bounded by 1927-1940, but actually weighted toward the first half of that span of years) she was a compositionally sophisticated and original visual thinker, constantly trying out new and unlikely photographic approaches. Like many of the important artists of that time, her narrative pivots through the Bauhaus (in 1927). And if her photographic contributions had only consisted of closely cropped portraits, steep Moholy-Nagy-esque looking down views, and skew angle surreal urban fragments (she made some of all of these), her relegation to the footnoted second tier would have been wholly understandable.

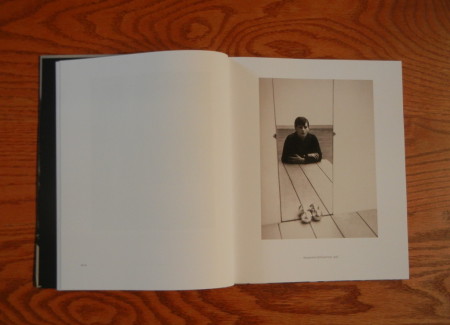

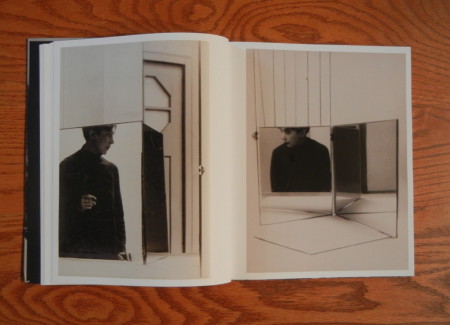

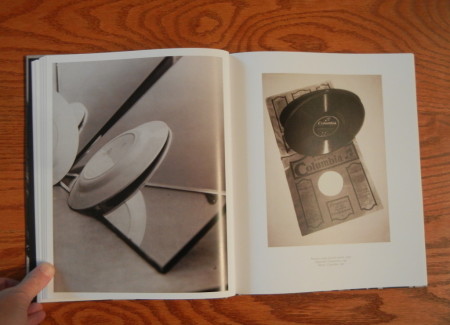

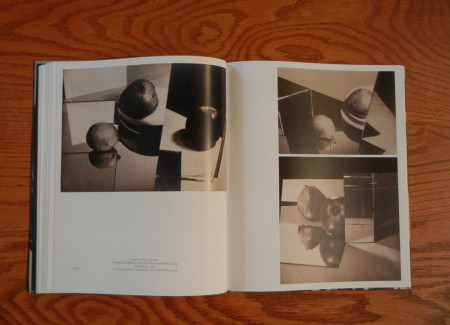

But in amongst these more common received ideas were some truly revolutionary disruptions, and these are the ones that mark her career with more authority. While plenty of photographers across the history of the medium have used mirrors to make self portraits, Henri latched onto the mirror as a vehicle for extending the tenets of Cubism and Constructivism, using reflections to fragment space, introduce multiple viewpoints, and seemingly upend photographic time. Beginning with relatively simple double portraits (of herself and her friends), her works quickly evolved into more complex studio constructions, with multiple mirrors angled to reflect each other, expanding the options for spatial uncertainty. Henri then combined shiny industrial balls (read by some with a Freudian twist), metal grates, bobbins, and thin meshes in elegant tabletop arrangements that multiplied into sharply confused visual puzzles, full of slashing angles and doubled echoes. These images easily stand among the best ever made in this genre (see Barbara Kasten’s recent ICA Philadelphia retrospective for a more recent extension of these foundation ideas).

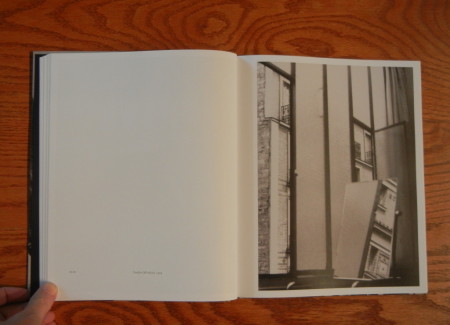

Henri went on to employ the mirrors in everything from exactingly composed refracted window studies to avant-garde commercial advertising setups, and just a few years later, she began experimenting with cut out paper images of fruit which she mixed in with real apples, pears, and lemons amid the mirrors. These layered “thing and itself” constructions are smartly precise, with areas of light and dark broken into geometric shards. Given the rephotography craze of the current moment, Henri’s dazzlingly reflected works here look uncontestably prescient; contemporary photographers from John Houck to Laura Letinsky are arguably retracing steps she laid some 80+ years ago. Henri went on to extend these ideas with other natural subjects as well, boldly doubling and tripling roses, clumps of leaves, and chunky stems in glassware. These lesser known images are nothing short of a revelation.

In the mid-1930s, Henri surprised us again, with a series of perception-challenging montaged works made in Rome. Cut out images of fallen columns, broken statuary, and angled brick walls have been overlapped into busy compositions that defy spatial reality, where edges fail to match and textures are mis-scaled. By letting us see the white rips and tears, she was consciously opening up her bag of tricks, bringing us into the conversation about the nature of photographic reality. A pair of later self portraits made using multiple exposures (with her head positioned inside empty frames) feel similarly overt; even as her photographic career was winding down and she was moving on to other interests, she was still innovating, pushing on the limits of photography to discover alternate ways of seeing.

Given the lack of authoritative research on Henri to date, this volume will deservingly become a reference staple, adding much needed detail, background, and analysis to the simple outline of her career. Particularly in her areas of brash innovation and their relevance to today’s photographic concerns, Henri deserves to be much better known. Hopefully, this excellent sampler of her work will catalyze more contemporary photographers to rediscover her flashes of brilliance.

Collector’s POV: Florence Henri’s work has an inconsistent secondary market history, with only a few lots coming up for sale in any given year in the past decade, primarily in European auctions. Prices have ranged from as little as roughly $1000 to as much as $25000, but this range may not take into account the market for her best work.