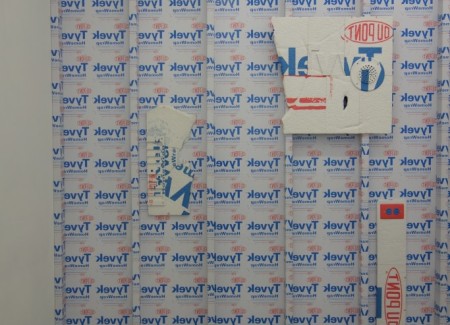

JTF (just the facts): A total of 23 works, mostly unframed, hung against white/Tyvek wrapped walls in the divided main gallery space and in the office area. 3 of the works are direct to substrate prints on vacuum formed PETG (with acrylic), made in 2015. These works range in size from 34×30 to 51×54 and are unique. Another 8 works are direct to substrate prints on solid surface Corian (with acrylic), made in 2015. Each of these works is sized 24×24 and is unique. And the remaining 12 works are 3D powder prints with UV varnish, made in 2015. These works range in size from roughly 7×2 to 26×28 and are unique, with one exception (a vent, available in an edition of 8+1AP). (Installation and detail shots below.)

Comments/Context: As Ethan Greenbaum’s new show demonstrates, the sculptural photographic object is on a fast evolutionary track, rapidly pulling it away from the simplistic definitions and boundaries of traditional photography. A handful of years ago, the power of digital printing gave us photographs that were printed on all kinds of unexpected substrates and surfaces, and at the time, those artworks seemed rebellious in their breaking of the unchallenged centrality of the two-dimensional paper print. With the benefit of recent hindsight, those same works now seem obvious – of course, we can print on plastic, or concrete, or vinyl, or a shower curtain, that’s a given; the more nuanced question facing us going forward is how that end product flexibility can enable something more than just a physical frame-breaking context change.

For Ethan Greenbaum, cumulative mastery of craft seems to have been the starting point for his ongoing innovations – an artist must systematically harness the power of his or her materials before moving on to aesthetically test their limits, and in Greenbaum’s case, these new printing technologies have been constantly changing and improving. Greenbaum has been making vacuum-formed plastic works investigating urban surfaces for several years now. In his first iterations, looking-down-at-the-sidewalk imagery was printed on one side of the glossy material and ceiling tiles were used to create raised square and rectangular surfaces pushed up from underneath; the results extended the investigation of visual surface detail into bubbled, bumpy, tactile topographies.

In his newest vacuum-formed works, Greenbaum takes those foundation ideas and practices several steps further. Photographic imagery is now printed on both sides of the clear material, allowing the underside image to show through the one on top, creating both subtle depth and intermixing, an effect almost akin to underpainting. He has also found ways to extend the vacuum process, allowing him to push gestural sweeps and marks into the plastic that become raised undulations and corrugations on the other side; this gives this surfaces more expressionistic interest. Leveraging these new techniques, these new works are the best he has made in this ongoing series. They’re treating photographic surface as a starting point for improvisation, and that idea is getting richer as complexity is layered in further.

Greenbaum’s recent Corian works invert this first idea, replacing the “push out” molding process with a removal/carving method. In this sense, the original cellphone photographs of various up-close built surfaces (bricks, drains, wood planks, vents) become digital maps, which are then converted into routed instructions for the milling tools. Once the synthetic stone has been carved, the images are printed on top and touched up with additional inks, filling in areas of three dimensionality exposed by the digging but not actually visible in the source photographs. Two things about this approach are intriguing – the textural contradictions of the materials (i.e. heavy stone being used to represent wood grain or sheet metal) and the transformation of the photograph into both image and underlying data set. It’s clear that conventional photography is just the first step in this artistic exploration, where the baseline image instructions are subsequently tweaked, built up, and then output in unconventional ways, often with misalignments and chance errors, leading to new artistic questions and answers.

Once we follow Greenbaum down the rabbit hole of image as data set, 3D printing is the next logical step – the output choices are even more open-ended and flexible. Here Greenbaum has gotten underneath exterior built surface and gone inside, to the building materials themselves. Using images of various corporate logos and construction brands (Dupont/Tyvek, Home Depot, Formica, Georgia Pacific, Pink Panther insulation etc.) as his source files, he has then printed those logos on (or better yet, in) the forms of air vents, ceiling ties, electrical outlets, and sawn 2x4s and 2x12s. Except in a few cases where Greenbaum has consciously skewed the printers midstream, the image color in these works goes uniformly through the objects – it’s not laid on the surface but embedded in each microlayer of the material itself like a core sample. Again with these works, Greenbaum is playing with representation, making powder look like rock, or wood (right down to the sawn edge serrations), or plastic. He’s also bringing language into the visual mix, using logos/words/names as visual elements that may or may not be matched with their underlying materials (or appearance of materials).

These works don’t have end results as photographs, but use photography as input, intermediate, and/or support structure, like a visual bridge from one artistic place to another. With each successive project, Greenbaum’s ideas are getting more physically sophisticated, pushing his photographic image objects closer and closer to the object end of that spectrum – at some point, they simply become sculpture, and must be judged with a different set of eyes and criteria (and in that realm, we might see connections to Robert Gober’s wallpapers and sinks or Richard Artschwager’s flattened sculptural objects). But I think it’s the undefined transition zone between mediums that Greenbaum is so smartly interrogating here – that place where an image and its physicality are so inextricably intermingled that they open up a new artistic door.

Collector’s POV: The works in this show are priced between $2000 for the smallest sculptural objects to $7600 for the largest vacuum-formed works, with many intermediate priced generally based on relative size. Greenbaum’s work has little secondary market history at this point, so gallery retail remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.