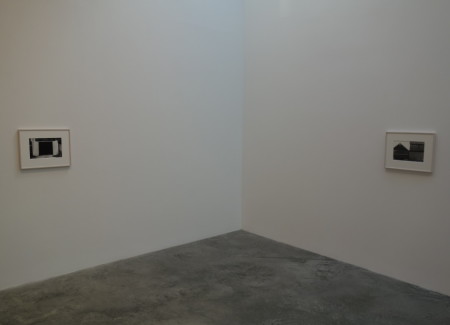

JTF (just the facts): A total of 31 black and white photographs, framed in white and matted, and hung against white walls in a series of three spacious rooms. All of the works are gelatin silver prints, made between 1950 and 1982 and printed recently. The prints are sized roughly 9×13 (or reverse) and are available in editions of 6. A monograph of this body of work is forthcoming from Aperture. (Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: Imagine that we play a guessing game where we try to describe what we think the esteemed American painter Ellsworth Kelly’s recently rediscovered black and white photographs might look like. Many contemporary painters have used stand alone photography as part of their larger artistic practice (think Warhol, Rauschenberg, Twombly and others), so it isn’t at all unusual that Kelly might have done so as well, even if the pictures were largely overlooked and stayed hidden away in storage boxes for decades.

Drawing on what we know of the best of Kelly’s hard edged, geometric paintings, in both black and white and color, we might reasonably assume that he would have an affinity for similar formal concerns in photography, as captured by the flattening eye of the camera. We might also guess that Kelly might have used the medium for casual visual note taking, recording fleeting arrangements and found abstractions that caught his eye, his aesthetic tendencies pulling him to see the world as a recurring parade of pared down polygons and rectangles. And we would have been right on most of these accounts, more or less.

But what we couldn’t have predicted is that Kelly was actually a talented photographer (full stop), not just an artistic shutterbug jotting down material to be repurposed later. While the strict formal clarity of his vision has echoes in the Modernist simplicity of Edward Weston, the pared down structure of Walker Evans, and the industrial precision of Lewis Baltz, his eye is uniquely Kelly, turning humble buildings and natural vistas into crisp exercises in compositional organization, often dominated bold contrasts and sharp lines.

The tonalities of black and white photography seem to have been tailor made for Kelly’s thinking. Many of his images start with the unassuming lines of a weathered barn (in both the United States and France, over the years), many of which were architecturally simple rectangles with triangular roofs and square doors. When seen against the whiteness of the unclouded sky and in the context of grassy middle grey surroundings, these barns become a series of geometric building blocks, often with elemental white against black juxtapositions and rooflines that line up and overlap with interlocking order. With a squint of the eyes to blur the detail, Kelly’s photographs become just like his paintings, studies in finding the balance in formal weights.

One the keys to Kelly’s photographic vision was his tendency to see shadows and voids not as detailed depths or negative space, but as flat planes of almost uniform blackness. This allowed him to turn everyday doorways and cellar openings into complex polygons. Angled shadows cut across slatted walls and pass down stuccoed entrances with knife edge sharpness, carving them into tilted geometries. And while many of his barns find balance in perfect black squares mirrored by flanking white doors, it’s the unadorned grace of his off kilter trapezoids and paired positive/negative shapes that comes through in picture after picture.

But this geometric thinking didn’t end with the built structures that were his most obvious visual quarry. He found similar angles and forms in plenty of unlikely places – newly paved sidewalk squares, balcony railings, movie screens, broken carpentry framing, painted traffic lines, broken windows, and shadows cast by street signs. Even nature, in the form of silhouetted tree branches and the gentle curves of snowy hillsides and riverbanks, provided him with found geometries.

While it is impossible to say exactly how Kelly’s photographs were involved in his larger artistic practice, there are some striking parallels to consider. One comes in his 1950 images of beach cabanas and brickwork in Meschers. These pictures break up a larger rectangle into slats of alternating dark and light tonalities, with an uneven, almost chance quality to the sewing and masonry. Then compare those visual ideas with his 1951 paintings (also made in Meschers) where he used rough brushwork to made black and white squares, which he then physically cut up and reassembled into striped, ladder-like layers. To my eye, the connection is obvious. Whether there is before/after causation hardly matters – what’s important is there seems to be credible evidence that photography was part of Kelly’s thinking process, even as he was working out ideas in paint (and cut paper). What’s also intriguing is that there are more photographs from the 1970s with these same kinds of slatted forms (boardwalk light leaks and stairway shadows), as if those ideas were being recycled and re-evaluated again some twenty years later. For museums with deep holdings of Kelly’s paintings, a grid of these photographs would provide a handy tutorial on how his singular vision was translated between mediums.

While not every one of these photographs is executed with the intense crispness a full-time photographer might have required, Kelly was a decent printer, and his contrasts of bright white and deep black are plenty strong enough to communicate his aesthetic intentions. And it’s those consistent choices that are the key takeaway from this show. When using his camera, it’s as if Kelly was applying a set of thoroughly ingrained artistic principles, even when he was just wandering. His photographs don’t feel as harshly minimal or conceptually rigid as we might reasonably have expected – they have a kind of inward-looking joy in them that is contagious, a personal reveling in the overlooked geometric order of the world that has been unexpectedly discovered in the everyday. He seems to have genuinely tapped into the look-at-that wonder of photography.

Collector’s POV: The works in this show are priced at $15000 each. While Kelly’s paintings and drawings have robust secondary markets, his photographs have only recently been rediscovered. As such, gallery retail remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.