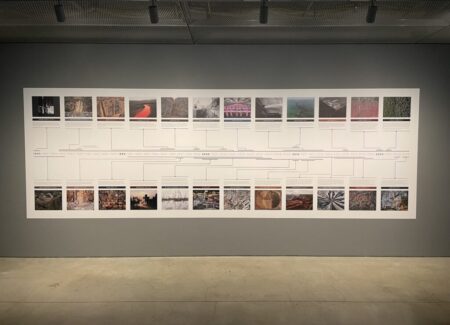

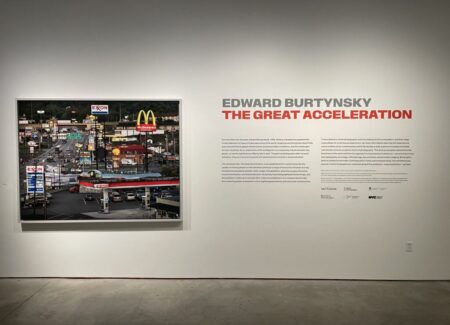

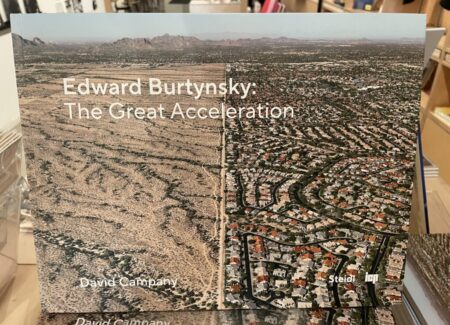

JTF (just the facts): A total of 88 color photographs, variously framed, matted, and displayed, and hung against grey and white walls on the second and third floors of the museum (including the catwalks). The small prints are framed in light grey wood and matted; the large prints are framed in light grey wood and unmatted. Includes a chronology (1976-2023). The exhibit was curated by David Campany. (Installation shots below.)

The following works are included in the show:

- 63 inkjet prints, 1981, 1982, 1983, 1984, 1985, 1986, 1996, 1997, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2014, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2020, 2022

- 4 inkjet print diptychs, 1996, 2002, 2003, 2005

- 3 large color prints affixed directly to wall, 2011, 2012

- (various photographers) 14 images of the artist at work, 1986, 1999, 2000, 2003, 2007, 2008, 2015, 2016, 2017

A catalog of the exhibit has been published by the museum (here). (Cover shot below.)

Comments/Context: One of the reasons a retrospective exhibition of an artist’s work is often so illuminating is that it doesn’t represent just a single moment in time or a single body of recent work, but a longer progression of sustained effort, sometimes over decades. When we can follow step-wise from an artist’s early images through to more current projects, we can start to see not just the pictures themselves, but the changes that have been taking place in between, in everything from subject matter to aesthetics. In a sense, a gallery show offers us a look at a single group of trees, while a retrospective steps back to take in the context of the whole forest.

The Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky has been honing his craft since the early 1980s, but in the context of our own years covering photography in New York, his rise has been very much a consistent part of our own history over the past 15 years or so. We have reviewed no less than seven of his solo gallery shows in the city, at four different spaces over the years – in 2023 (reviewed here), 2018 (reviewed here), 2016 (reviewed here), 2013 (reviewed here), 2011 (reviewed here), 2011 again (reviewed here), and 2009 (reviewed here) – as well as thinking intermittently about his photobooks, his participation in museum group shows and art fairs, and the results of his works sold at auction. In some cases, we have raved; in others, we have felt conflicted by the tension between grandiose beauty and ecological tragedy found in many of his most astonishing pictures. It is of course inevitable that from project to project, as he has continued to challenge himself, there would be some variation in the degree of success he has been able to achieve in any one series, and we have tried to tag along and consider the merits of each one with thoughtfulness. But across the board, it is clear that Burtynsky has continued to distinguish himself in both his consistent attention to the complexities of his photographic craft and in his durable commitment to wrestling with the larger challenges we face in the way we humans treat the world around us.

Since our attention to Burtynsky’s photographic career began in the late 2000s, the first two decades of his artistic output before that time on view here are of particular interest, in that they help set the stage for what came later. The first pictures in this exhibit, from the early 1980s, are modest, textural landscape views taken near the artist’s home in Canada, and in many ways, their attention to the subtle beauty of nature makes sense as a starting point for the environmental activism that would come to define Burtynsky’s viewpoint decades later – from the very beginning, it seems he was keenly aware of the fragility of the natural world, and sought to document its overlooked grace. From there, Burtynsky turned his attention to the way people were controlling nature, in the form of food production. In images of greenhouses, food packing, and larger scale processing plants, he started to notice the visual patterns of regular plantings, long conveyor belts, and organized processing steps, turning greenhouse cucumber plants, piles of carrots, and hanging chicken carcasses into patterned compositions.

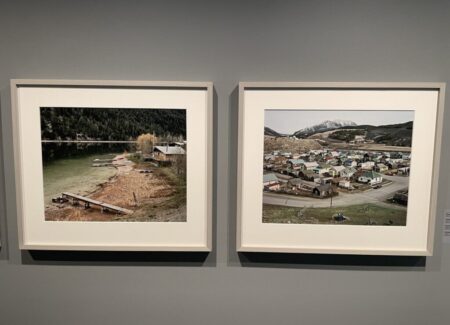

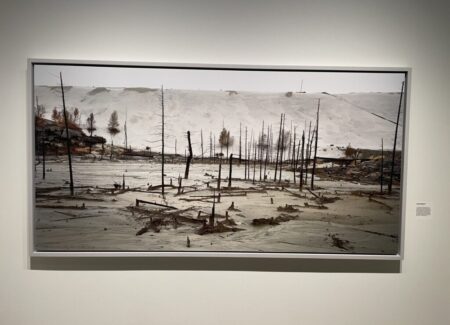

A 1983 image Burtynsky made at Mount St. Helens in Washington is another early signpost. The mountain volcano erupted in 1980, charring the landscape, casting ash for miles, and blowing down trees like matchsticks. Burtynsky visited the site a few years afterward, and the destruction was still widespread – from an elevated vantage point, his photograph captures the scarred land, the fallen trees and choking ash blanketing the rolling hillsides miles from the blast site. We can then trace this same raised perspective to a project Burtynsky called “Broken Ground”, which featured views of homesteads, small towns, and railcuts through the land. These images interrogate the same man-altered landscape tensions found in the work of the New Topographics photographers from the 1970s, and if we aren’t careful, we could easily mistake a few of these 1980s Burtynsky homestead views for elevated pictures made by Joel Sternfeld. These photographs then lead directly to Burtynsky’s first images of quarries, mines, and tailing ponds, which expand on his deliberate investigations into intentional alterations of the environment. What’s fascinating is that by the end of 1980s, this incremental progression of artistic experiments and learnings ultimately led to the solidification of most of the conceptual and aesthetic pieces of Burtynsky’s ongoing artistic worldview.

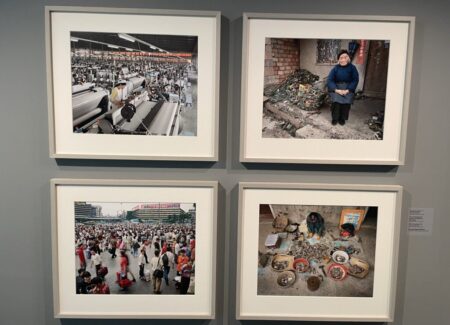

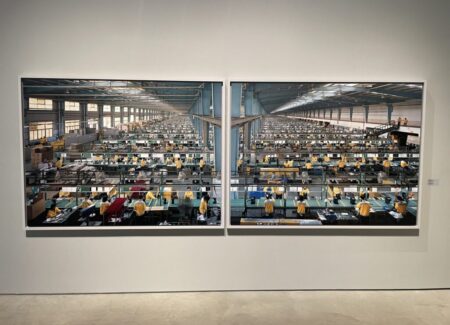

What comes next, throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s, is an increase in scale. Burtynksy continues documenting the various extraction industries, in far flung locations around the globe, and given the immense size of these operations, as he steps back further and further to take them in visually, the scope of his compositions gets wider and wider. Soon he leans further into this investigation of breadth, elevation, and scale, in piles of discarded tires, in large scale recycling plants, in shipbreaking on the tidal flats in Bangladesh, and ultimately to China, where the massive commercial factories and the extensive transformations of the Three Gorges Dam project bring scale to the forefront. At roughly this same time, Düsseldorf photographers like Andreas Gursky and Thomas Struth, coming out of the rigorous teachings of Bernd and Hilla Becher, were pioneering the use of massive photographic scale in their work, and Burtynsky has to have been aware of their activities. So between the actual scale of Burtnysky’s chosen subjects and the evolution of scale in contemporary photography going on around him, those roads merge and lead Burtynsky to larger and larger prints filled with detail edge to edge.

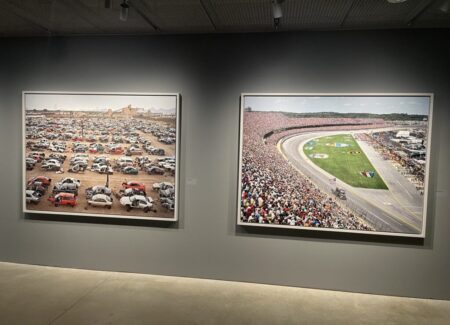

With Burtynsky’s wide ranging study of the world of oil, beginning with views of the oil fields themselves, but soon reaching out to numerous downstream endpoints and conclusions, the last piece of the Burtynsky puzzle slides into place. For his career as an artist, it’s a linchpin project, because for the first time, he brings an overt sense of advocacy to his photographic perspective – it’s a climate change project, with images that take a particular cautionary stand, and he’s not afraid of wrestling with or exposing the complexities on which our fossil-fueled world is built. Here he shows us endless arrays of pumpjacks, but also car junk yards, motor racing spectacles, tangled Los Angeles highways, and the jumble of logos along our roadsides, the scale of our oil addiction writ large. The consistent success of these images lies in their merging of attentive observational scale with the bite of urgent artistic activism, a combination that would become, in the years to follow, Burtynsky’s artistic signature.

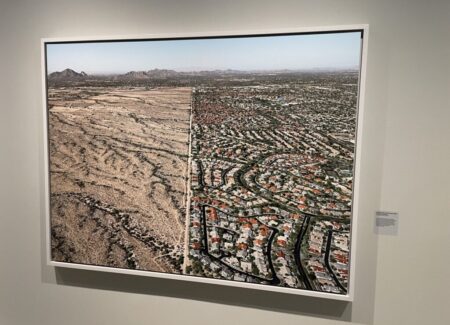

Much of the artist’s work in the past two decades has taken this fundamental mindset and applied it to different environmental issues, conditions, and locations, from water usage and farming techniques to deep underground drilling and salt mining. The exhibit blends all of these later projects into a tightly-edited survey of these many immersive realities, jumping from one strikingly large picture to the next, with each successive subject seemingly requiring better and more elaborate technology to capture the scene Burtynsky wants, in the form of helicopters, aerial drones, and other ambitious approaches. And as the world has been pushed to ecological extremes, so too have Burtynsky’s photographs, becoming increasingly abstract and often almost too beautiful, in some cases, their astonishing decorative grandeur in color and pattern distracting us from the horrors they actually document.

One exciting side note to this show is how well it handles the notoriously difficult exhibition design challenge of the ICP’s huge two-story wall. The solution is the largest single photograph I can remember seeing in a museum exhibit, a towering print from Burtynsky’s “Pivot Irrigation” series, covering the wall from floor to ceiling with a circle and several stripes in tones of tactile brown and grey, almost like a Sean Scully painting. As a picture, it both asks us to address issues with agricultural water use and seduces us with its bold geometric design, its stunning scale making us feel small and requiring us to look up at its massiveness. In an exhibit titled “The Great Acceleration”, it’s the logical limit point to Burtynsky’s dance with ever increasing scale, but unlike just any photograph printed large to fill the available space, Burtynsky’s extra large print is an inspired extension of his underlying aesthetic philosophy.

Since Burtynsky’s art, particularly of late, inextricably entwines examples of ecological manipulation (and disaster) with the artist’s interpretation of those sites, it can become difficult to separate our outrage with the conditions on the ground and our more arm’s length reaction to his photographic perspective. And while many who visit this show will simply take away a better appreciation for the fragility of our natural world, and perhaps even feel compelled to take action to protect it more fully, there is of course an artistic career on view here as well. And what this exhibit does so successfully is chart how Burtynsky initially merged several different aesthetic ideas, added scale, and then amplified his approach with a stronger sense of urgent action and direction, transforming his picture-making (and his life) into something more like global photographic activism.

Collector’s POV: Since this is a museum exhibition, there are of course no posted prices. Burtynsky has a large number of gallery representation relationships, across the US and Canada and around the world, including Nicholas Metivier Gallery in Toronto (here), Howard Greenberg Gallery in New York (here), Sundaram Tagore Gallery in New York (here), and many others. Burtynsky’s prints have become consistently available in the secondary markets in recent years, with prices at auction ranging between roughly $2000 and $100000.