JTF (just the facts): A survey show consisting of 8 bodies of work, including photographs, video, sound, and collected ephemera, made between 2010 to 2018.

The details for each project are as follows:

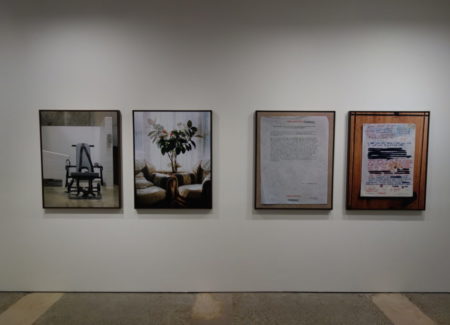

- Guantanamo: If the Light Goes Out, 2010: 34 digital chromogenic prints

- Letters to Omar, 2010: inkjet prints

- Section 4, Part 20: One Day on a Saturday, 2011: looped video and sound, 7:37

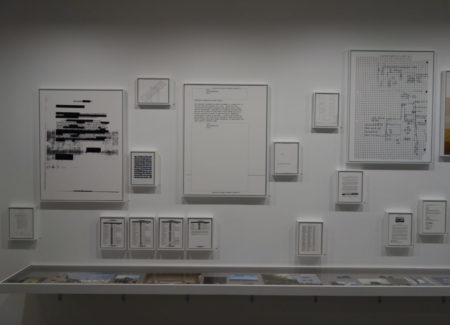

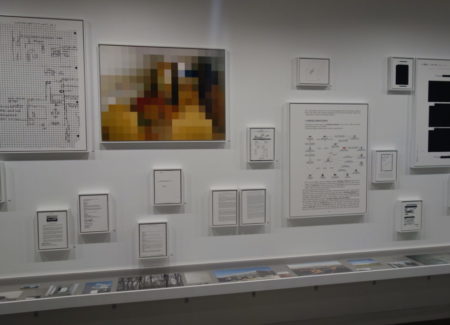

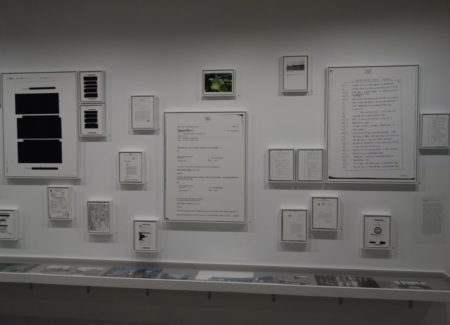

- Negative Publicity: Artefacts of Extraordinary Rendition, 2016: 74 inkjet prints

- Orange Screen, 2016: video, 6:30

- Body Politic, 2016: installation with video and vinyl wallpaper, 5:00

- American Pie, 2018: text and audio, 8:36

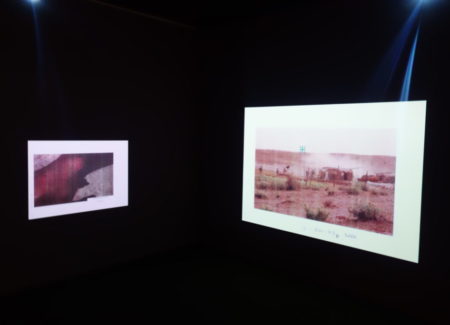

- 198/2000, 2018: installation, projected images

(Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: When we examine the long history of war photography, the meaty heart of the story lies in the 20th century. Due to the efforts the many talented and intrepid photojournalists who stepped in to actively document conflicts taking place around the globe in the past century, we have deep and extensive archives of imagery from World War I, World War II, the war in Vietnam, and countless other regional flare-ups, civil wars, and instances of national aggression. These pictures show us the up-close reality of these wars, detailing the combatants on both sides, the intensity of the action in battle, the more subtle behaviors and ideas that led to the spark of war, and ultimately the death, destruction, and enduring horrors that were left behind. The collective photographic record provides a rich permanent context for the fleeting events that took place on the ground.

The wars of the 19th century are not nearly so well documented, largely because the photographic technology of the day was too slow and cumbersome to follow the frenetic action. The images that have survived from the American civil war and various European conflicts in the second half of the 1800s tend to be before and after pictures, where we can first see troops assembling and then later see smoky fields dotted with corpses left behind, the action in between largely left to our imagination. Since formal portraits were made standing still, our images of generals and enlisted men from these conflicts tend to be staged in clean uniforms, rather than in the mud, blood, and general grimness of war.

When we jump back to the 21st century, we would rightly assume that there are now plenty of cameras around to document our newfangled wars. And while many of the recent conflicts in Iraq, Afghanistan, and other places in the Middle East have been (and continue to be) blanketed by embedded television, magazine, and newspaper coverage, the so-called War on Terror that began after the attacks on the World Trade Center in New York in 2001 and continues in various evolved forms even today has been a much more elusive subject for the world’s photojournalists and image makers.

While there is of course a public face to the War on Terror, where victims and perpetrators alike are frequently brought before the cameras, the war has no easily understood fronts, battles, timelines, or even objectives (aside from the celebrated capture/killing of Osama bin Laden) – it is largely a secret operation, or at least a shadowy one, where one side plots targeted disruptions and acts of rebellion/insurgency and the other side attempts to interrupt those plots and systematically dismantle the groups that plan them. Embedded in this complex back and forth are thorny questions of security, power, and legality, with layers of nationalism and religion hardening and sometimes exaggerating the positions of the ever-evolving opposing forces.

From a photographic perspective, there is almost nothing (and no one) to photograph, which makes the British photographer Edmund Clark’s decade long investigation of various facets of the invisible War on Terror all the more vexing. The threads he has so diligently and persistently followed have nearly always led to ghosts and frustration – censorship, non-cooperation, redaction, misdirection, outright misinformation and propaganda, or at best grudging acknowledgement and foot-dragging confirmation. How Clark has attempted to make sense, and art, out of this mountain of fuzzy incompletion is in many ways the central subject of this show.

The journey begins with Clark’s 2010 visit to the U.S. Naval Station at Guantanamo Bay in Cuba, where terror suspects have been and are still being interrogated and detained. Since neither military personnel nor the detainees themselves could be photographed, Clark’s images attempt to tell their interwoven stories via indirect portraiture, where empty cells and officers’ quarters act as stand-ins for the actual people involved. The pictures are sober, with details like chain link cages, metal tables, plywood huts, and plain white clothing sketching in the lives of the detainees. Medical facilities, feeding chairs, shackles, and riot gear offer an even darker side to the proceedings, while a child’s plastic slide, a tiki bar, and a movie screening allude to the lives of the Americans on the other side of the incarceration transaction. A few images follow the detainees home, where they try to rebuild their lives with grassy yards and Welcome Home pillows. Seen together, Clark’s empty photographs capture an eerie sense of disorientation and unease, the less savory parts of the process taking place off stage.

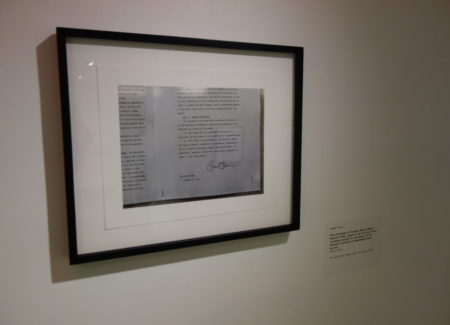

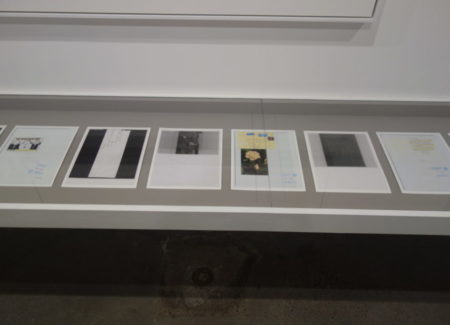

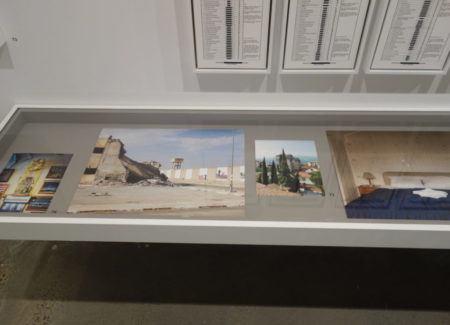

But this is the closest we get to actually seeing the War on Terror in some kind of action. One wall of the show is filled with Clark’s archive of information on the extraordinary rendition process, where detainees were captured, transported to “black sites” around the world, and interrogated using “enhanced” techniques like waterboarding. Entitled “Negative Publicity”, it acts like a figure/ground exercise, where the figure is the invisible extradition activites and the ground is everything Clark has found/documented about what was going on. An extended vitrine of color images documents forgettable office blocks, airport hangars, houses, parking lots, and conference rooms, where pilots lived, trips were scheduled, and contractors operated to fulfill mysterious government contracts. But once again, the principal actors are missing, their stories filled in by reams of reproduced documents, memos, and instructions hung salon-style on the nearby walls. Engaging with Clark’s artwork is like unsuccessfully trying to piece together a puzzle, where we seem to have some key fragments of information but the entire picture remains maddeningly out of reach.

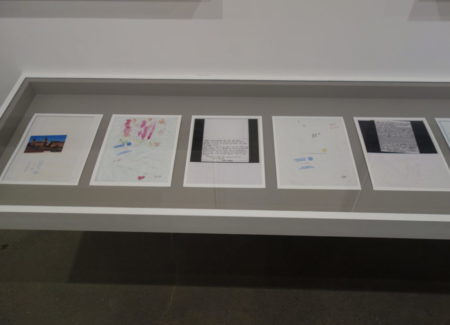

Other works on view follow even more indirect threads. “Letters to Omar” reproduces a selection redacted letters written to the Guantanamo inmate Omar Deghayes, the pages largely empty of messages, save a few sunflowers, cats, and small incomprehensible drawings. “198/2000” creates an immersive installation of prison photographs released by the US military, the out-of-context injuries, measuring, and random body parts providing an incomplete record of treatment (and abuses) we are left to imagine. “Section 4 Part 20: One Day on a Saturday” interleaves two voice recordings, one of an American woman reading from a detainee control procedures manual released by Wikileaks, the other an Arab man recounting an “unofficial interrogation”, the combination of bureaucratic rules and harrowing miscommunication set against placid postcard views of sheep and butterflies. And if that repeated snippet of Don McClean’s “American Pie” that plays in the entryway starts to annoy you (as it certainly did me), that’s entirely on purpose, as it is part of a playlist of American songs (including Eminem, Metallica, and others) used to disorient detainees during interrogations.

What is both fascinating and troubling about all of Clark’s efforts is that although he has been undeniably methodical, tenacious, and even forensic in his investigative work, the results are mildly unsatisfying – there is no payoff, no answer, no easy conclusion. The reason that unease is so unsettling is that he has, in a sense, held up a mirror to ourselves; this is how we operate now, how our culture has collectively decided to respond to its threats. It would be naive to think that we could handle such aggressions without compromises, but Clark’s work shines a light on the choices we have made and the details we keep secret, and the results aren’t always flattering.

In the end, Clark hasn’t succeeded in photographing the unphotographable War on Terror, but he’s made a sustained and thoughtful effort to do what we can to keep us thinking about its many implications. With cyber wars, Internet bots, and international disinformation on the rise, the idea that a camera can document these ongoing incursions and battles may be increasingly optimistic, so indirect models like the kind Clark is exploring may increasingly be an effective way to leverage photography in narrating these kinds of inherently invisible stories.

Collector’s POV: Since this is a museum show, there are of course no posted prices. Edmund Clark is represented in New York by Flowers Gallery (here). Clark’s work has not yet entered the secondary markets with much consistency, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.

I think a more accurate terminology would be War ‘of’ terror.