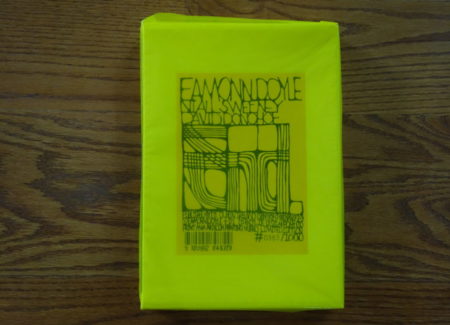

JTF (just the facts): Self-published (by D1, Dublin) in 2016 (here). Coauthored by Niall Sweeney and David Donohoe. 13 separate sections, gathered in a white leatherette slipcase, and wrapped in yellow cellophane. Includes a total of 273 black and white and color photographs, 20 ink drawings, and 1 7-inch vinyl recording. Of the 13 sections, 6 are thread sewn books (3 full color, 2 silver ink on black, 1 black on yellow), 5 are concertina-folded, double sided diptychs and triptychs, 1 is an oversized double sided page, and the last is a yellow glassine poster that when folded encloses the record. There are no essays or texts. In an edition of 1000. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: I suppose we can say that it was inevitable. With all the activity and risk taking going on in the world of photobook publishing, at some point, the explosion of creativity that has fueled the fire over the past several years was (predictably) going to outpace itself. And when it did, we would start to see photobooks that have effectively lost their way, well intended but ultimately misguided publications where the elaborate look-at-me construction features pile up to the point that the photography being featured gets drowned out. For me, Eamonn Doyle’s End, however innovative that it is, is tangible evidence that we have reached this unfortunate tipping point.

End is the final book of a three-part series chronicling street life in modern Dublin that began with the much acclaimed i (from 2014) and On (from 2015, reviewed here). And while those two first books were single approach photographic efforts, alternately employing elevated color views and underneath/shadowy black and white images of passersby on the city sidewalks, End opts for a more open-ended mix of varying photographic styles, borrowing from the earlier techniques and adding in additional ideas, including interdisciplinary overlaid ink drawings and a musical score by other artists.

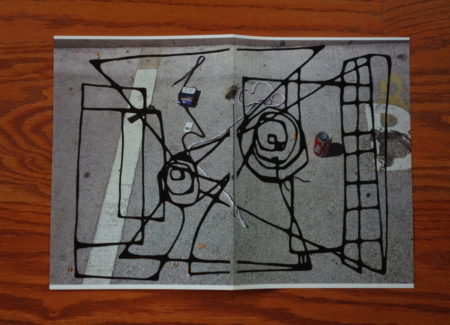

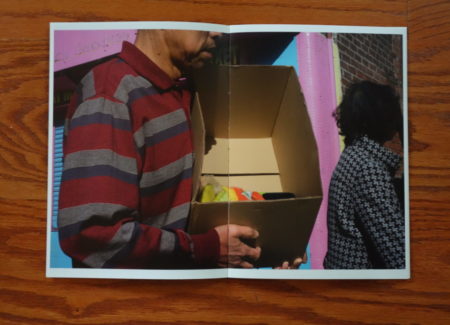

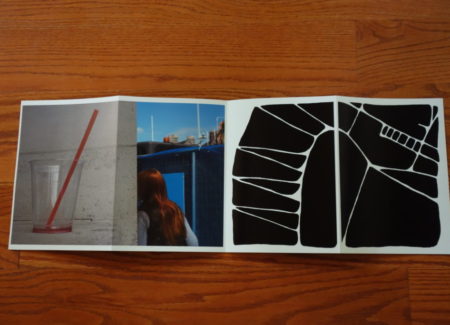

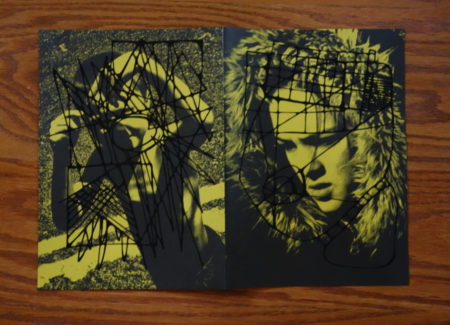

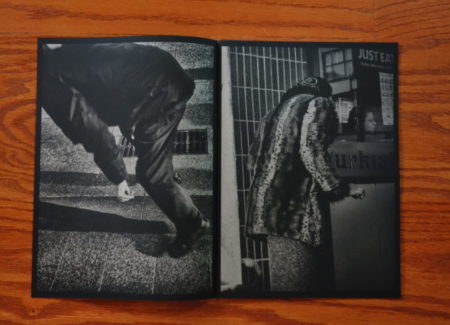

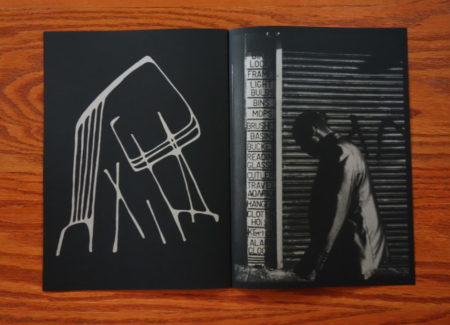

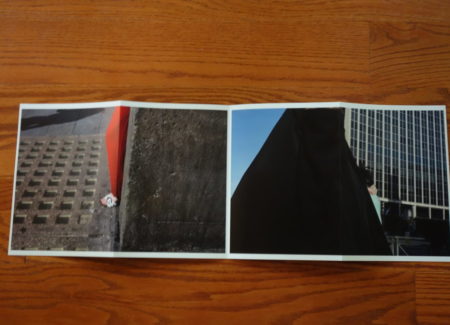

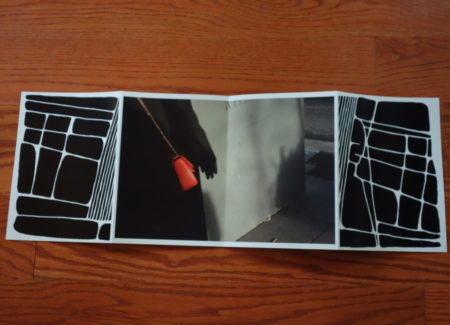

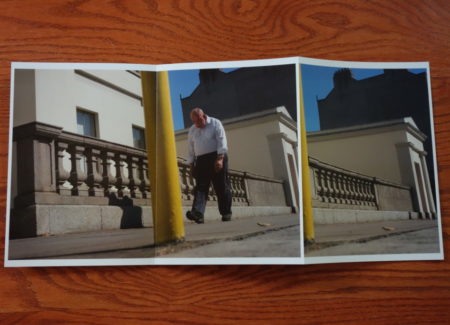

To call End a photobook is really a misnomer – it’s a sprawling compendium of artist designed booklets, thick stock foldouts, and posters, housed in a hardcover (leatherette) sleeve (wrapped in cellophane). Only after the 13 separate items spill out into your hands does it become apparent that there are some repeated themes – most importantly, the color works are displayed in booklets and on two-sided foldouts with white borders, and the black and white works are printed in monochrome booklets in silver and yellow. This is where the every-trick-in-the-book publishing style (papers, sizes, finishes, techniques) gets a bit overwhelming and distracting, and perhaps intentionally so – Doyle’s imagery ends up feeling all over the place and fragmentary amid this chaos of stuff, but maybe this is a reflection of what he thinks contemporary Dublin feels like.

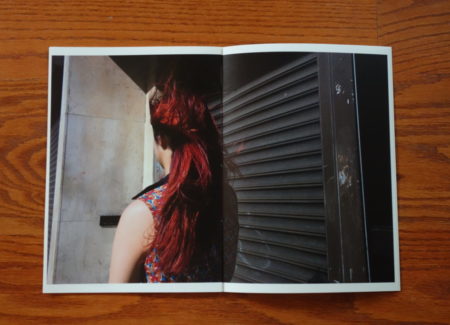

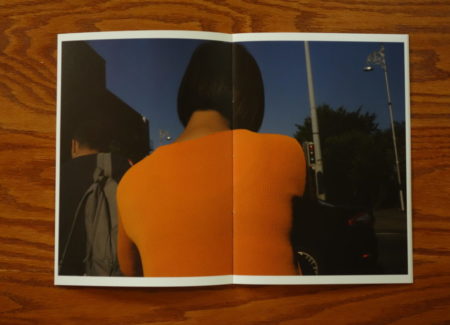

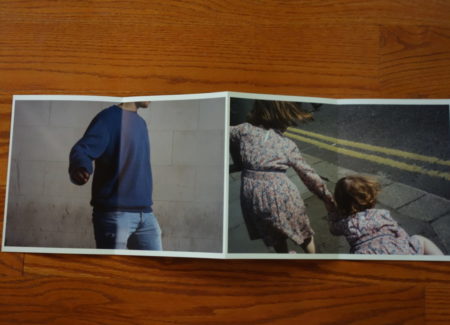

My frustration with this surfeit of cool ideas is that Doyle’s photographs are often excellent, and the way they are presented often kept me from entirely enjoying them. In color, his images tend to center in one a single formal element, gesture, or color that dominates the composition, and many of these isolated fragments are surprisingly lithe and elegant. Sprays of red hair, an orange sweater, a red purse, a purple dress, and a blue skirt each jump out of the stream of pedestrians with engrossing intensity, each a singular moment where something ordinary becomes unexpectedly amazing. The same can be said of two girls tugging on each other in floral patterned dresses, their frozen movement and swirling hair somehow gloriously elemental. Motifs of dance and choreography subtly recur, an outstretched arm, a striding leg, or a cast shadow silhouette turning the ordinary hustle of the streets into a parade of expressive human movement. And a few images play with Paul Graham-style split second time dilation, where a pose and its context are incrementally changing over a series of frames.

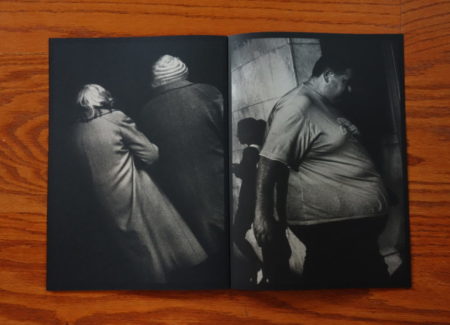

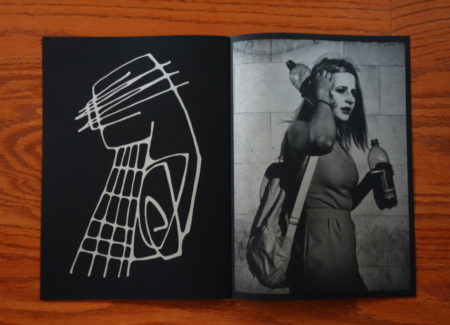

In black and white, Doyle seems more intent on exploring patterns and surfaces, and the use of silver ink adds a hint of sheen to many of these images – a fat man’s t-shirt, a flowing headscarf, and a suit jacket all seem to shimmer in the burnished light. Other pictures are exercises in all-over pattern, from electrical wires and tree branches in the sky to rectangular concrete paving stones, striped steel security gates, and animal print outerwear closer to the ground. Here shadows and reflections are an ever present force, and Doyle uses them to multiply bodies and interrupt views. The inclusion of the fluid ink drawings works best with these images in black and white, as the parallels between the lines and forms of the two mediums are more resonant. And the booklet in yellow monochrome takes these ideas further, starting with photographs full of denser patterns and more effusive gestures, and then intermingling them with staccato drawings laid right on top.

Given all the discrete physical pieces in this puzzle of a photobook, the experiential result is a lot of flipping and turning, picking up and putting down, which in a sense reinforces a feeling of things constantly coming and going in this city, with hints and visual echoes tying it all together. Intellectually, that works, but in person, it feels forced and a bit precious. Without all the bells and whistles, this photobook (and its solid photography) wouldn’t have been as eye-catching or unusual, but a cleaner, more streamlined design might have done a better job of helping the photographs communicate their largely well-crafted messages. I’m sure to some End will feel like a triumph of fanciful ingenuity and object-quality inventiveness, but to me, it feels like a publishing project that went too far and was in need of a stubborn editor who could have reined in some of its excesses. In End, we seem to have discovered the limit of over-the-top too-muchness, its title a prophetic comment on photobooks gone wild.

Collector’s POV: Eamonn Doyle is represented by Michael Hoppen Gallery in London (here). His work has little secondary market history at this point, so gallery retail remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.

1. I’m surprised at the review, looking at the introductory pictures I thought you were going to love it. 2. the ‘must try harder’ book-design-mania has a way to run yet, I think – and collectordaily has probably played a big part in stoking that, and which has not necessarily been a bad thing. 3. Doyle is a terrific photographer, and that still seems to shine through sufficiently, but you’re the one who had to wrestle with the ‘object’. 4. a lot of photographers are insecure about their status as real ‘artists’, even the most massively successful, and can end up doing proper art-type left-field things to reassure themselves, which are sometimes OK. 5. that line ‘photobooks gone wild’ – brilliant. I’m still laughing : D

When Martin Parr noticed a few years back that Eamon Doyle is the most relevant and creative street photographer at the moment and has finally brought new life into that very important genre, I couldn’t agree more.

This man’s vision is not only unique, his approach is so refreshing that the demise of street photography has finally been halted.

With this new approach it is of course nescessary that the viewer, the critic and collector open their eyes and recognize this new vision.

But reading this review of the latest of his books, they are all three amazing by the way, this critic is still frozen in time with the endless generic approach of photographers and artists who use photography where they believe that any picture taken on the street is just brilliant.

Nothing could be further from the truth, the genre has been emptied sucked dry for decades and has become stagnant and boring, no matter who and how important the name of the photographer is.

For once don’t pay any attention to this review and actually look at the work, no matter that he lives far away in Dublin and doubles as a music producer to make some money.

If any comparison is apt, it would be that Eamon Doyle is a new version of the young Robert Frank.

With regards, Jan De Bont

If you disagree with this observation