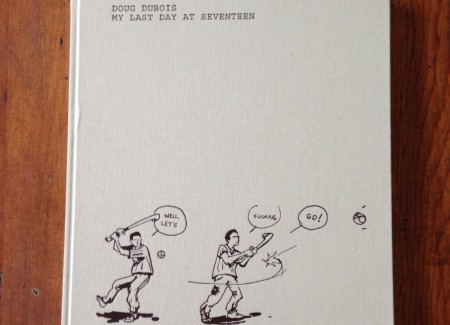

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2015 by Aperture (here). Hardcover in tan cloth (9 3/8 inches by 12 ½ inches), 156 pages, with 79 color images. Includes inserts of illustrations by the Irish children’s book artist Patrick Lynch as well as transcriptions of dialogues between DuBois and his subjects. $60 (Spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Nelson Algren’s third rule of life—after “never play cards with a man named Doc” and “never eat at a place called Mom’s”—was “never sleep with a woman whose troubles are worse than your own.”

Romance would be duller if people chose to follow this advice, and Algren certainly didn’t. He was a philandering gambler and heavy drinker whose three marriages were brief. His troubles were often worse than his paramours. If women were supposed to heed his prohibition, too, Simone de Beauvoir would never have been his lover—and she was. What’s more, failure to obey his third rule could only have been good for his fiction. Literature is unthinkable without stories of people whose lives are worse than our own.

The same might be said of documentary photography. Ever since John Thomson and Jacob Riis took their cameras into the slums of London and New York, economic misery in lands of plenty has been a vital subject in photography and reporting on persistent inequality has been an honorable calling for photojournalists.

But the warning in Algren’s axiom, which is really about the potential for cruelty (and guilt) in any unbalanced relationship, explains much of the post-1970s criticism of traditional documentary. Susan Sontag scorned Diane Arbus for exploiting the mentally retarded. Walker Evans caught fire from all sides in the ‘80s and ‘90s (from Howell Raines as well as Paula Rabinowitz) for demeaning the share cropper families of Hale County, Alabama during the Great Depression. Photographing troubled people was then—and is now, in some quarters—asking for trouble.

Since then, politically sensitive photographers have tried to present their work in ways that granted more power to their subjects. Jim Goldberg in Rich and Poor (1985) and Raised by Wolves (1995) asked the people in his photographs (men and women, elders and homeless teens) to write about their reactions to his portrayal of them. Susan Meiselas’s Kurdistan (1997) incorporated all sorts of historical and contemporary evidence from the lives of the Kurds into the pages of her book, in addition to her portraits of them. Eugene Richards, Andrea Modica, Susan Lipper, Mark Steinmetz, Donna Ferrato, Boris Mikhailov, Chris Killip, Paul Graham and a host of others have devised various strategies to bridge distance, lessen disparity, and complicate narrative and reader response.

Doug DuBois’s marvelous book about the teenage inhabitants of a housing estate in Cobh, a small economically depressed town in Cork County, Ireland, is yet another answer to this dilemma. In his previous book, All the Days and Nights (2009), a portrait of his parents, sister, and nephew over 20 years, he could not be accused of misrepresenting people he didn’t know well. Supplementing his photographs with notes about the failing health of his father and mother, he was an attached observer with genetic and emotional ties to almost everyone in his pictures.

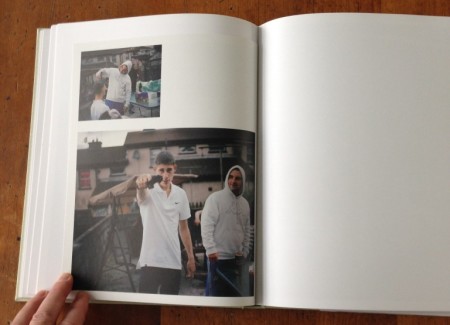

My Last Day at Seventeen is a riskier venture. The potential for unwarranted conclusions or touristic superficiality about lives he knew only from afar was much greater. Unlike everyone in these pictures, he is not Irish or poor or undirected or young. Even though this project lasted off-and-on for 5 years, he was documenting an Irish clan that was as proudly insular as the Roma in Josef Koudelka’s classic photographs from the 1960s.

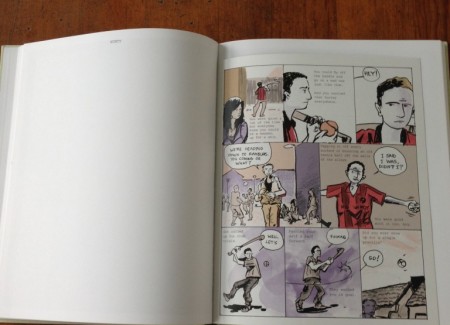

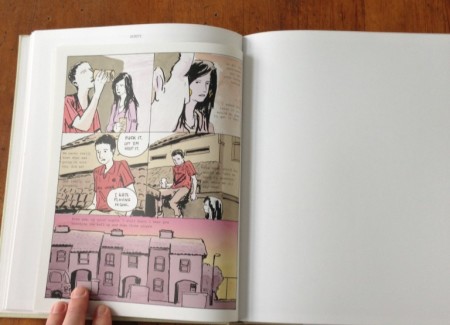

The decision to blend his own portraits of the young people and their town with inserts from a graphic novel by the Irish writer and illustrator Patrick Lynch offers several advantages. Lynch’s inked panels, filled with airy brown lines and slangy dialogue balloons, contrast with the smooth descriptions of DuBois’s still color photographs. Lynch’s fictional characters may or may not be based on the teens in the images. By relinquishing absolute authorial control, DuBois has freed himself to work around the edges.

The result is more of an Irish book than an American one, which is as it should be. Audiences here may have difficulty translating some of Lynch’s stories, with their talk about hurley and club trials and expressions like “what’s the craic?” But every country and income bracket is populated with teens like these, who experiment with drugs, booze, sex, and violence and who suffer from boredom and depression, leading in some cases to unplanned pregnancies and suicide.

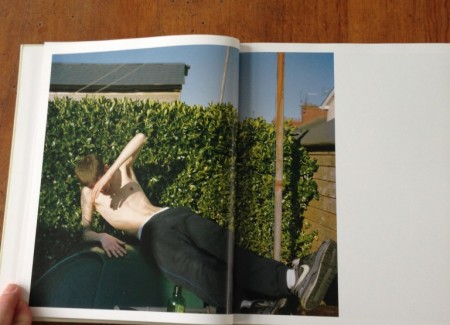

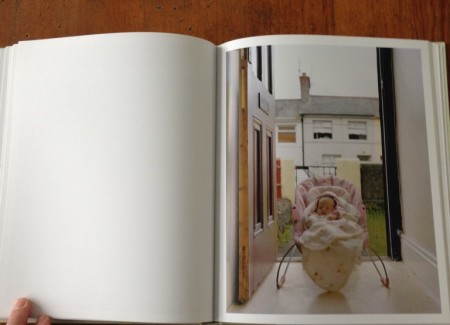

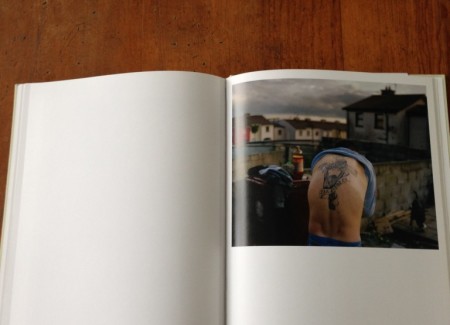

The decision to exclude the parents from his frames allows DuBois to make it seem as though he has handed over supervision of the book to his subject. They are on the cusp of adult responsibility. They know it awaits them and some already have babies, but most don’t have to shoulder a work-a-day job yet, and so for perhaps the last time in their lives, the boys can run around shirtless, wielding guns and hurley sticks, behaving recklessly while the females can don their shortest dresses and dye their hair cranberry red.

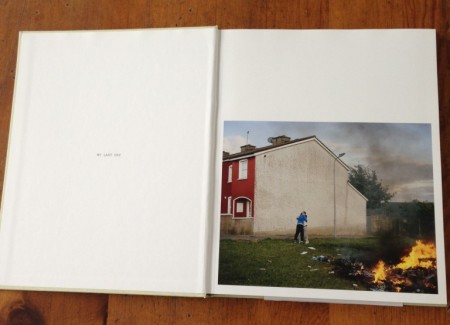

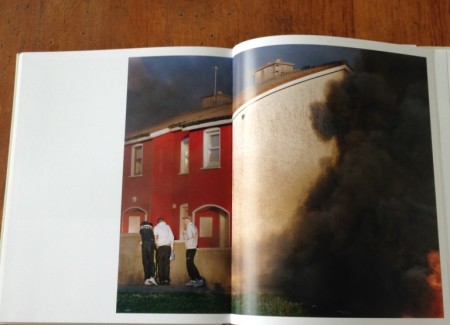

DuBois’s photographs are more atmospheric than topological. The architecture in Cobh is uniform and low-cost, but it’s a seaside town. Leaving it is hard, and staying may be harder. No one seems to have much money, and everyone can stand on the rocky shoreline and look out at larger horizons even if they aren’t going anywhere.

No single character dominates the narrative, an indication that growing up here is an experience enforced by group identity. DuBois alternates close-ups of his pale-skinned characters, with longer views of streets and beaches. On his daily strolls, he seems to have come across more than a few set fires blazing in sideyards as well the occasional startling image, such as one of a barking white greyhound surrounded by a murder of flying crows.

I have known and liked DuBois’s work since the 1990s when I was editor-at-large for Doubletake magazine and he regularly published there. I don’t believe he has done better work than he does here.

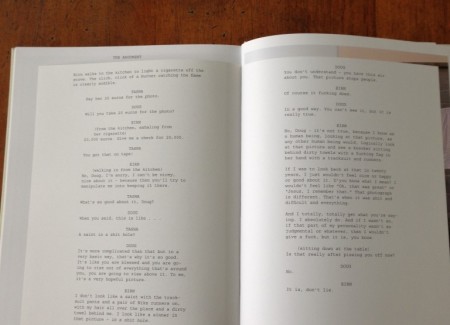

The last few pages is a printed dialogue between the photographer and a young woman, who objects to a portrait he wants to include in the book.

EIRN

“Oh my God, you have that one at the end: That now is not being put in the book, Doug, I’ll tell you that now for a fact….There’s not a fucking hope.”

DOUG

You don’t understand—you have this air about you. That picture stops people.

EIRN

Of course it fucking does.

DOUG

In a good way. You can’t see it, but it is really true.

EIRN

No, Doug—it’s not true, because I know as a human being, looking at that picture, as any other human being would, logically look at that picture and see a knacker sitting behind dirty towels with a fucking fag in his her hand with a tracksuit and runners.

If I was to look back at that in twenty years, I just wouldn’t feel nice or happy or good about it.”

(How they settle the argument is an ingenious compromise the details of which won’t be disclosed here.)

One could say that DuBois presents a story about teens in peril that others, including Goldberg and Mary Ellen Mark, have told before. But just because we may think we know what’s in store for these kids doesn’t make their fate any less poignant or guarantee that our guesses are—or will be—correct. When the hazardous world of secretive adolescence is portrayed with the curious generosity that DuBois has shown toward the boys and girls of Cobh, it would be unfair to them, to him, and to ourselves not to read to the end and imagine all the possibilities.

Collector’s POV: Doug DuBois’ gallery representation isn’t entirely clear—he has had solo and group shows in New York and elsewhere over the past decade, but the venues haven’t been consistent. His work also has little secondary market history. As a result, interested collectors should likely follow up directly with the photographer via his website (linked in the sidebar).