JTF (just the facts): A total of 24 photographs, framed in white and matted, and hung against light grey and white walls in the two room gallery space.

The show includes:

- 4 gelatin silver prints, 1982, 1984, 1987, 2019, 16×20 inches (or the reverse)

- 17 gelatin silver prints, 1980, 1986, 1987, 1989, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1996, 2000, 2011, 2013, 2017, 2018, 2019, 11×14 inches (or the reverse)

- 3 chromogenic prints, 1985, 1999, 16×20 inches (or the reverse)

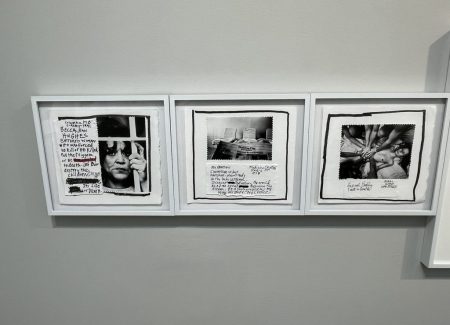

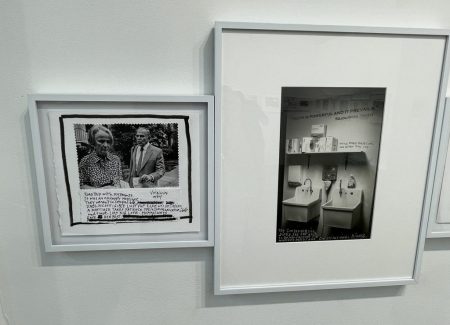

- 35 collages (paper, ink, paint, gelatin silver prints), various sizes, undated

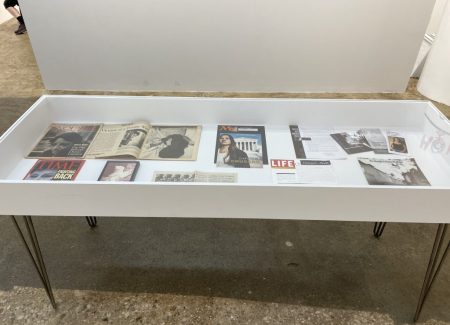

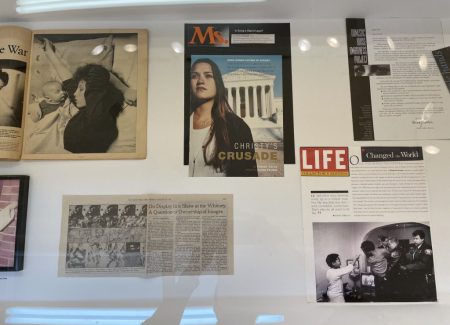

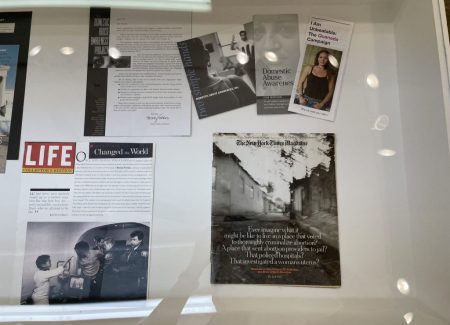

- 1 vitrine with various magazines, newspapers, pamphlets, and other ephemera.

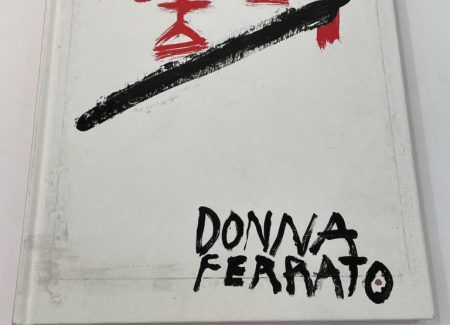

A monograph of this body of work was published in 2021 by powerhouse Books (here). Hardcover with red edging, 9×10.5 inches, 176 pages, with 120 images. Includes texts by the artist. Design by the artist. (Cover shot below.)

Comments/Context: In the tumultuous aftermath of the recent overturning of Roe v. Wade, and the subsequent banning (or severely restricting) of abortion in many states around the country, we find ourselves in a cultural moment where the changes in abortion rights are just one piece of a wider regressive tide that seems to want to turn back women’s rights in all forms. And while we have seen this kind of conservatism push back on the hard fought progress of women’s equality before, the situation has quickly intensified of late with the overt move backward by the Supreme Court.

It is against this highly charged backdrop of current events that Donna Ferrato’s show Holy arrives to deliver a cathartic blast of confident female positive resilience. An esteemed photojournalist, Ferrato is likely best known for her 1991 photobook Living with the Enemy, which boldly documented the lives of women who were the victims of domestic violence and abuse. Holy (in both gallery show and photobook forms) reprises some of the most powerful images from that landmark project, and then uses them as a foundation on which to build a broader study of the struggles (and triumphs) women face in finding and grasping their own liberation. Ferrato ably jumps from the political to the spiritual, and from the sexual to the domestic, tracking the various feminine roles of mother, daughter, wife, and strong-willed individual (among others). She documents the contours and complexities of women’s lives with sensitivity, empathy, and candor, tying them all together into one gloriously unified, self-reliant whole.

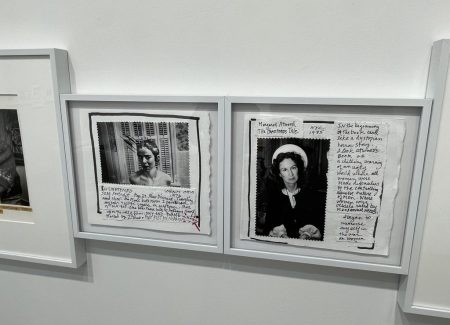

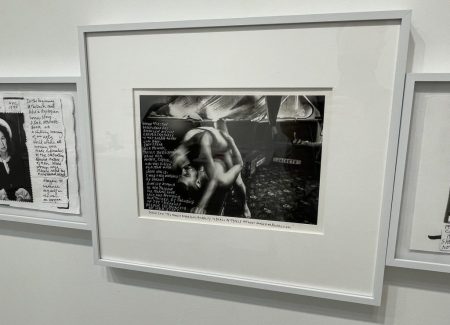

Most of the early pictures (from the 1980s) in this show find Ferrato taking on the photojournalistic position of active (and sometimes involved) witness, where intimate connection with the subjects ultimately led to the intense moments she recorded on film. “Elisabeth’s Night of Horror” from 1982 is perhaps the most visceral of these images, as it captures the moment of abuse as it happened, with Ferrato actually reflected in the bathroom mirror just as the furious slap swept across the woman’s face. This immediacy of violence then gives way to moments of high emotional trauma and recourse, as young children attempt to protect their mothers and the police arrive to haul off abusive fathers and boyfriends. “Diamond, Minneapolis, MN” and “Daughter Saves Mother, Minneapolis, MN”, both from 1987, document the erupting hatred of a finger-pointing son and the blank faced resignation of a daughter as the broken situations of abuse finally lead to the removal of the perpetrators. Ferrato’s portraits of “Rita” and “Janice” then dig deeper into the layered psychological aftermath of such violence, with the defiant black eyes of a woman who prosecuted her husband balanced by tearful despondency when the killer of a friend was given a lenient sentence.

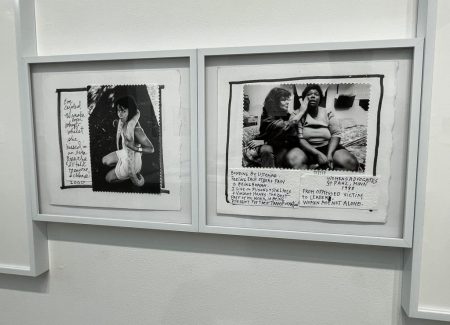

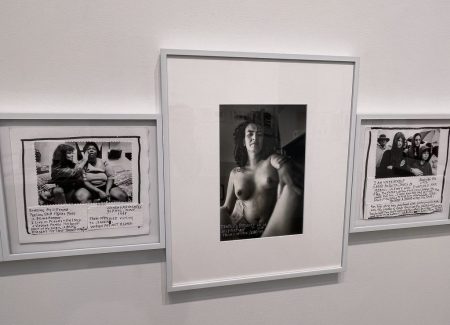

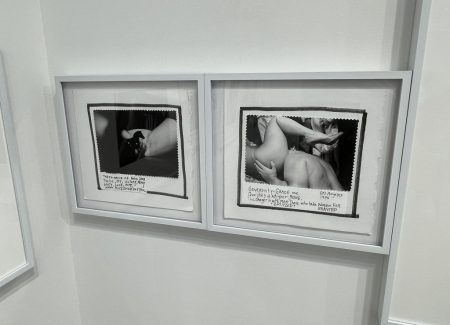

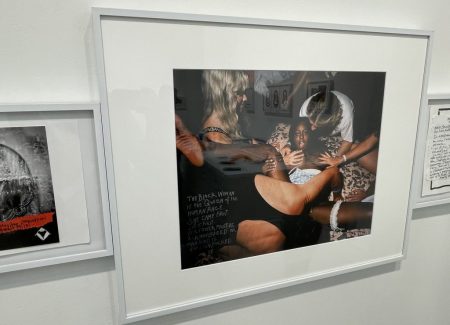

In the years since Living with the Enemy was published, Ferrato’s photographic scope has widened, following female empowerment in many different forms and guises. Many of the images on view document sexual positivity, in the most inclusive sense of the phrase. Ferrato shows us women on their own, with partners, and in groups; as straight, gay, and trans; both young and old; in bodies of all shapes, sizes, and races; and as dancers, entertainers, and sex workers. And the point of this expansive diversity is that it all works – Ferrato is universally supportive and non-judgmental, as long as the women are feeling good about what is going on. The joy and playfulness in the sexiness of these pictures is altogether contagious and reinforcing; there is ecstasy, desire, passion, confident performance, intimacy, vulnerability, appreciation, and trust in large doses, with women nearly always in the center of the action and comfortable with the sharing taking place.

Motherhood is another thread that runs through many of Ferrato’s strongest photographs, and abortion is inherently pulled into that set of life choices and decisions (rather than isolated and externalized from women as an abstraction). Ferrato connects the twinned pain/ecstasy of a homebirth, a woman who chose to have her forearm amputated (due to bone cancer) rather than give up her unborn child, and the artist’s own choice to have an abortion, creating a continuum of valid alternatives that all place the agency (and responsibility) in the hands of the women themselves. The strength of mothers (including Ferrato’s own) comes through again and again in these and other pictures, with mothers as protectors, teachers, caregivers, sacrificers, nurturers, pain-bearers, supporters, listeners, soldiers, protestors, and general badasses.

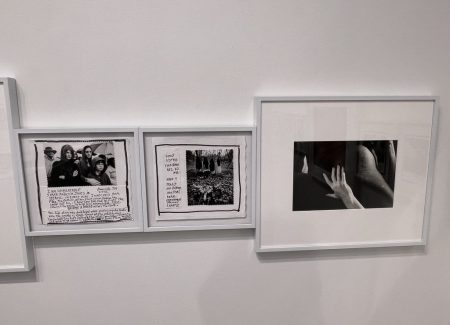

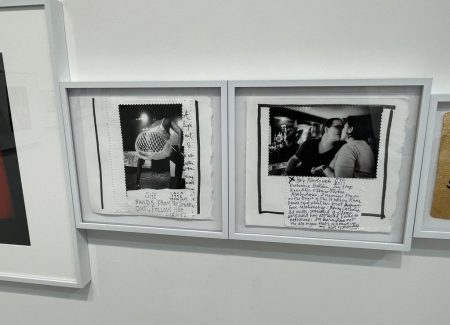

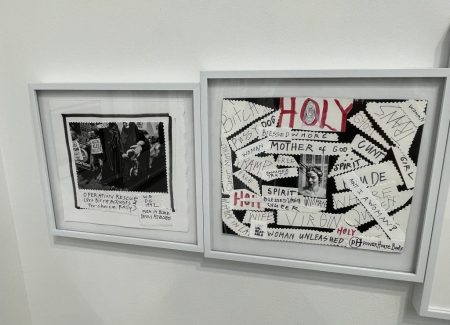

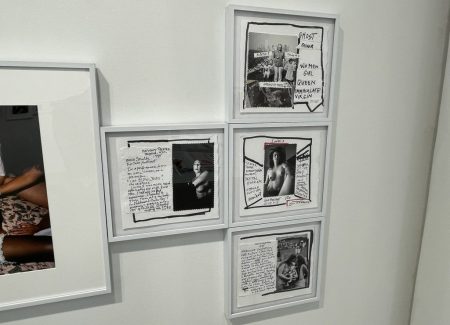

All of Ferrato’s photographs include hand-inscribed captions, which expand the available visual evidence into larger stories, with names, places, and background events to provide context; some even sum up the path of an entire life, irrespective of the moment captured by the camera. This personal interaction with the pictures is taken further in a series of collages Ferrato made in 2018-2019, essentially as a maquette for what became the photobook version of Holy. Seen as expressive riffs on or re-imagined embellishments to Ferrato’s original photographs, the collages amplify Ferrato’s unique aesthetics. Mounted on tactile white paper, surrounded by bold borders, and layered together with the artist’s all capitals handwriting, the collages feel even more raw and immediate than Ferrato’s more traditional photographs, creating a flow of energy that liberally mixes storytelling approaches.

While summertime in the art world is often filled with easy going, innocuous lightness, Ferrato’s Holy is just the opposite – it’s a gut punch knockout that will leave you breathless, outraged, amped up, and energized. It consistently shows women in control, of their minds, bodies, and spirits, often forcefully struggling against men and society at large to make their way through the world. As seen here, the best of Ferrato’s photographs tap into a self-assured sense of steely positivity, where even the traumas and violence of life as a woman can be borne and overcome. And while many of these pictures offer an unabashedly raw view into these struggles, Ferrato never loses sight of a consistent strain of optimism. In the end, out of the darkness, this body of work is relentlessly encouraging, finding extraordinary fighting spirit in women many have overlooked.

Collector’s POV: The prints in this show are priced at $5500, $6500, or $8500, based on size, and the prints are uneditioned. The collages are $4500 each and unique. Ferrato’s work has little secondary market history at this point, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.