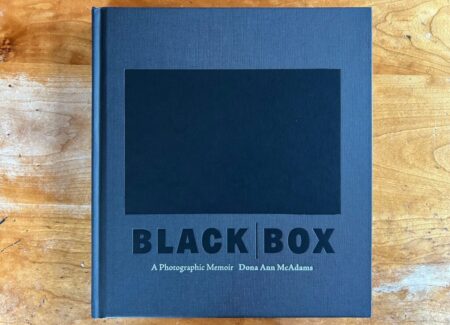

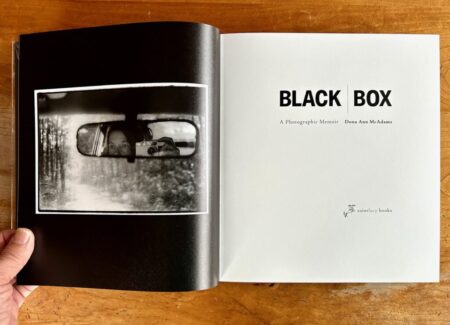

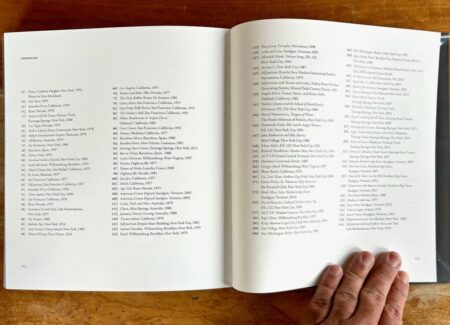

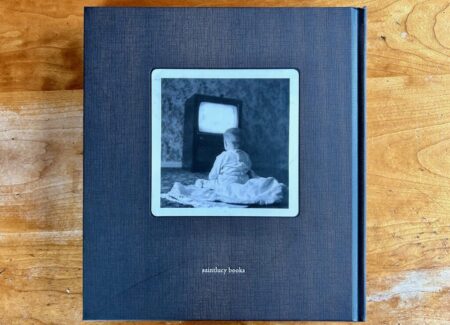

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2024 by Saint Lucy Books (here). Clothbound hardback with tipped in rear cover photograph, 10 x 9 inches, 256 pages, with 106 monochrome photographs and one color image. Includes an essay by Joanna Howard. Design by Guenet Abraham. (Cover and spread shots below.)

An exhibition of Black Box will be on view at Pratt Manhattan Gallery in NYC (here) April 18 – June 7, 2025, with an opening reception April 17, and public conversation with Eileen Myles on May 15.

Comments/Context: Dona Ann McAdams is a beloved figure among creatives. Her network expands wider than usual, encompassing fellow photographers along with illustrators, activists, jockeys, and goatherds. She’s the first degree of separation connecting Harvey Milk, Angela Davis, David Bowie, John Malkovich, David Wojnarowicz, and Maurice Sendak. The breadth of her community hints at a multifarious life now entering its eighth decade. Photography has been one primary through line, but McAdams’ career has bobbed and weaved through various disciplines, locations, art scenes, awards, and commissions. For those keeping score at home, tracking all of her various relationships and accomplishments has been a challenge, at least until now.

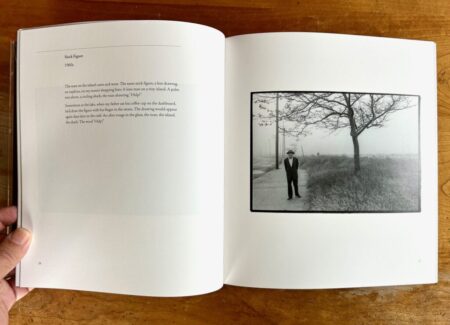

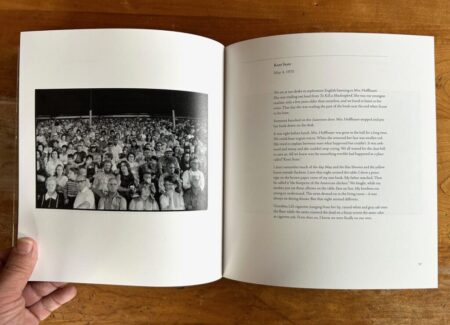

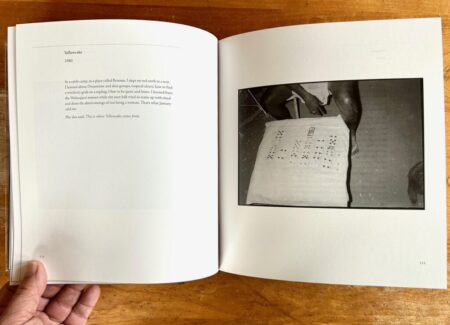

McAdams’ latest book should help set the record straight. Black Box: A Photographic Memoir is an autobiography of sorts, but the book is not structured as a typical prose narrative. Instead it blends photographs with so-called “ditties”, brief diaristic texts which McAdams has been writing and collecting for the past decade. As she describes ditties in the book’s epilogue, she thinks of them as “melodies for the photographs”. She first began drafting them when her brother died in 2013, handwriting with a number 4 pencil on white-lined papers, often while working in the darkroom. With the publication of this memoir, she has now stopped. The ditties filled a brief temporal window, not unlike a photographic exposure.

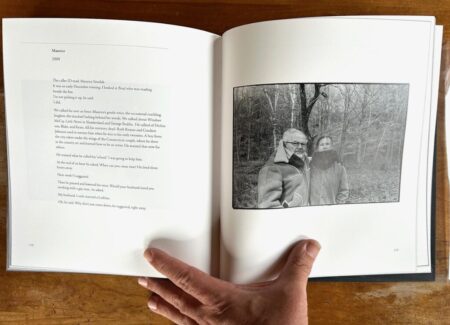

Pictures and ditties are interspersed throughout Black Box in roughly equal measure. Each series follows the same general chronology from 1954 to the present. But the two streams rarely relate to one another directly. Instead, the photos sketch certain life events while the ditties describe other ones from the same period. The two threads weave around each other at a brisk pace, often alternating per page, and occasionally continuing in one vein for several spreads.

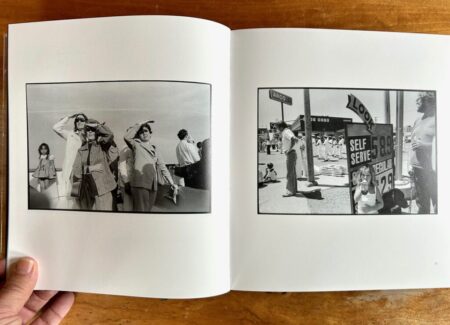

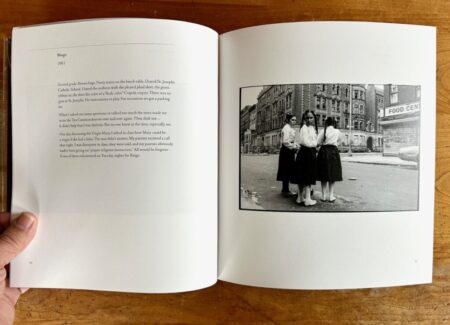

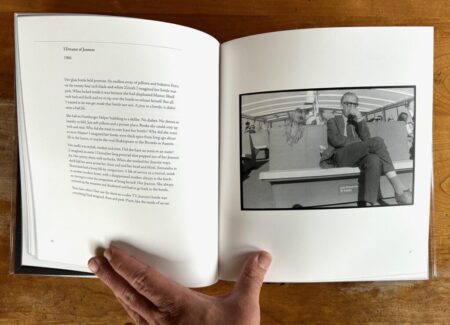

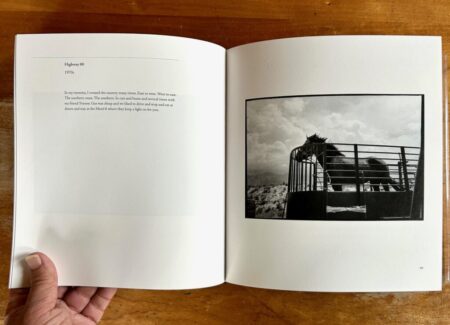

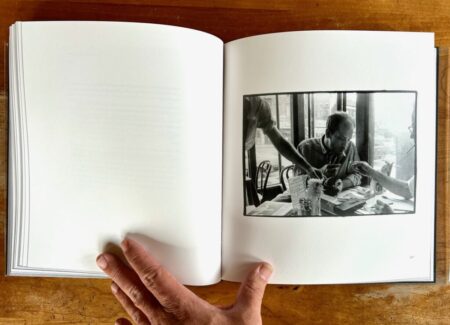

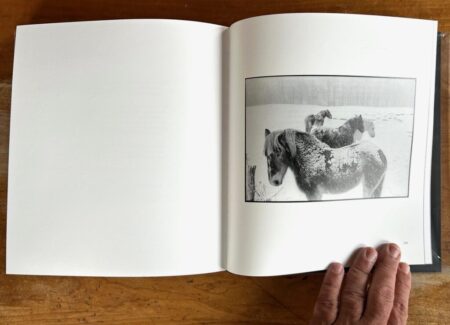

With two distinct forms narrating twin plot lines, wrestling both into a cohesive narrative must have been a challenge. If so, McAdams makes it look like a breeze. Whether by text or picture, the reader is carried along easily. Most will consume this page-turner in one or two evenings. McAdams pictures push the pace. She’s a strong photographer with a consistent visual style. Almost all of the photos are 35 mm black-and-white pictures, shot with various Leicas and printed with full frame borders in bygone analog fashion. Whether shooting a street scene in San Francisco, a muddy dance performance, or horses in a snowdrift, her authorship is never in doubt.

McAdams’ photographic reputation is confirmed, but we already knew that side of her. The greater revelation of Black Box is McAdams’ prose, which might be even better than her photos. From a dyslexic childhood, she has matured into a writer of refreshing purity, with a voice which is witty, honest and expressive. “The Blarney runs thick in my veins,” she deadpans. That helps to explain the lack of pretentious airs or tedious rhetoric which so often bogs down photobook texts. These ditties are a joy compared to such tracts. McAdams writes as naturally as milking a goat.

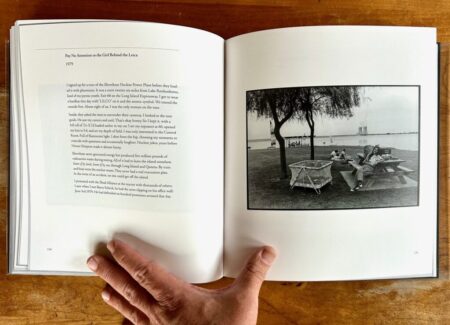

There’s not space to recount her entire biography here. But it’s worth highlighting a few key artistic moments. McAdams was born in 1954—the year of the horse—and grew up on Long Island. A photo of infant Dona in 1955 viewing a TV screen (reproduced on the rear cover) augurs her later interest in media and performance. Her first exposure to photography came as a mixed message. On a 1972 high school trip to MoMA she was entranced by Diane Arbus’ recently published monograph in the bookshop. Could she write about Arbus for her class assignment, she asked the teacher. “You can’t,” she was informed. “Photography is not art.”

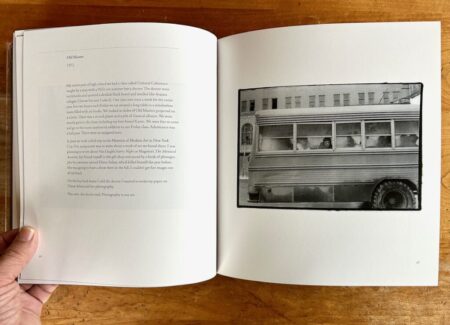

This being the early 1970s, McAdams ignored the admonition and headed west. Within a few months she’d resettled in San Francisco, where she sat in on photo classes at SFAI. Her instructor was none other than Hank Wessel. “[He] had a little beard and short brown hair,” she recalls. “His worn M2 never left his neck.” One day he invited a guest teacher to class by the name of Garry Winogrand. “Garry looked at a photo I’d taken on Geary Street, one of my first,” she writes. “Then he pronounced to the class: This is a really good photograph.” Readers can judge Garry’s verdict for themselves on the next page. The photo in question shows a busy sidewalk scene from 1974. Several pedestrians frame a seated woman with a newspaper, in a compositional arc of unlikely perfection. A really good photograph indeed.

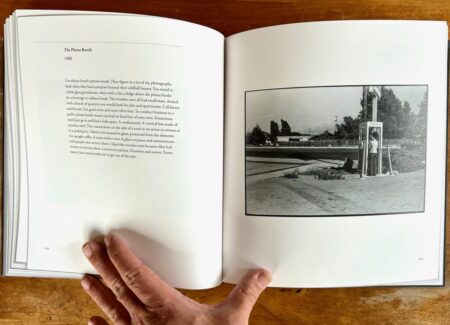

In a sign of things to come, McAdams had found herself in the right place at the right time. “Photography was having a heyday,” Wessel told his students. He urged them to do whatever they wanted so long as it was “a good photograph.” Wessel’s flexible dictum guided McAdams during the class, and in the decades to follow. She ditched her Olympus half-frame for a Leica in 1973. After that it was open season on the world. Black Box traces a whirlwind of subsequent adventures, through Harvey Milk’s camera shop and across Australia and America, working a series of menial jobs, before finally circling back to New York City in 1979, where McAdams could be closer to roots and family.

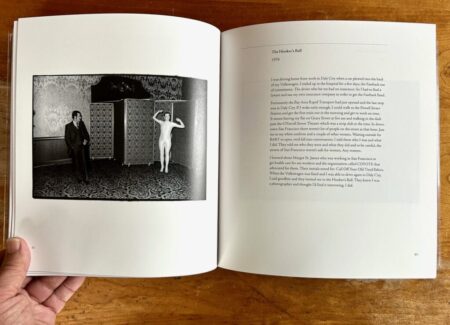

To be a photographer requires a keen sense of space and moment, and it seems McAdams had once again arrived at just the right place and time. New York’s art scene was exploding in the early 1980s, centered around the East Village. She soon became the house photographer at P.S. 122 on 1st Avenue. Shooting live performances as well as back stage, she documented thousands of people and events over 23 years. Some pictures were closely guarded, e.g. a nude photo of mud-caked Karen Finley in 1989. Others became iconic. The PS 122 work was eventually compiled into McAdams first monograph, Caught In The Act published in 1996 by Aperture. If the general public knows McAdams’ work, it is likely through those photographs (or perhaps for a photo of two girls on a sidewalk grate, which went viral much later).

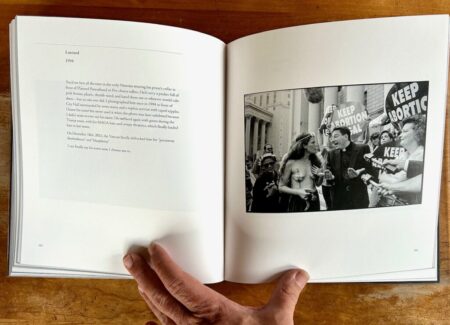

A few pictures from Caught In The Act are included in Black Box, along with many delicious asides. Meredith Monk makes a brief appearance—captured mid swirl with dance-whipped hair—followed by Yoshiko Chuma, Diamanda Galas, Karen Finley, Eileen Myles, and others. If women are heavily represented in McAdams’ oeuvre, the inclusion is deliberate. “Everyone knew about the male gaze,” she writes, “but the female gaze interested me more.”

Regardless of gender, NYC’s movers and shakers tailored themselves for the spotlight, ideal material for both photos and anecdotes. But McAdams had already made that book, and Black Box does not linger long in New York City. Soon enough she is off to greener pastures, literally. After some projects documenting demonstrations, nuclear power, the mentally ill, homeless shelters, and (remembering her birth year) horse stables, McAdams eventually settled on a goat farm in Vermont. Long story short, she lives there today with her husband, the novelist Brad Kessler. Just the right place and time to write a photographic memoir.

Black Box joins an increasingly crowded field of similar tomes. Perhaps it’s the Baby Boomers coming of age? Or maybe advances in printing technology have eased the graphic design challenges? Whatever the reason, we’ve seen a flurry of photographer memoirs in recent years: Stephen Shore’s Modern Instances, Sally Mann’s Hold Still, Lucy Lippard’s Stuff, Jim Goldberg’s Coming and Going, Ed Templeton’s Wires Crossed, and Danny Lyon’s This Is My Life I’m Talking About, to name a few. Each one blends text and pictures in its own way, with generally thought provoking and impactful results.

So there is competition in the genre. But Black Box carves out its own niche, largely due to its smart editing and design. No other book divides photos and ditties with such stark unity. They’re bound together into a thick brick of pages, with black gilded edges inside a black cloth cover. A black box, in other words. The title refers vaguely to a passage from 1979, when McAdams had just left San Francisco and “found myself in a box”. This ditty sits across the spread from one of the book’s few self-portraits. McAdams photographs herself boxed into a New York skyscraper, aiming into a mirror behind her Leica. Of course the Leica—like any camera—is essentially a black box, a container for light sealed darkness.

Viewed in this context, the book is constructed like a photographic exposure. Pictures capture slivers of the world. So do bite-sized ditties, casting brief incidents through a verbal lens. Whether using camera or pen, McAdams strips away extraneous stuff, translates the remainder into something usable, then composes it into a tidy package. Right place, right time, right curation. But this is just conjecture, guessing at the inner workings of McAdams’ Black Box. The true meaning of her long artistic journey may be impenetrable.

Collector’s POV: Dona Ann McAdams does not appear to have gallery representation at this time. Interested collectors should likely follow up directly with the artist via her website (linked in the sidebar).

Thanks for the thoughtful review, Blake.

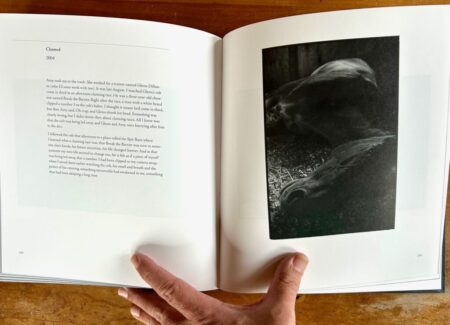

Claimed, 2004 (page 202)

‘A claiming race is a race in which every horse running can be “claimed” or purchased after the race. It is open to current owners, new owners or those getting back in the sport. It is a simple, quick and easy way to purchase a racehorse that is ready to run straight away’, from racehorseownership.ie, (not a source I ever expected to be quoting).