JTF (just the facts): Co-published in 2024 by Aperture (here) and Atelier EXB (here). Hardcover (11 x 8.5 x 1.5 inches), 144 pages, with 70 color and black-and-white photographs. Includes texts by the artist. Design by Coline Aguettaz. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Five years ago the Armenian-American photographer Diana Markosian published her first photobook titled Santa Barbara (reviewed here). It is a moving and brave re-enactment of her family’s story, including their journey from post-Soviet Russia of the 1990s to the sunny shores of Santa Barbara, California, in search of a brighter future. In this book, we learn that Markosian arrived in the United States with her mother and older brother when she was seven, and it took twenty years for her mother Svetlana to share the true story behind their move. As it turns out, their previous life was only getting more and more grim after the collapse of the Soviet Union: Svetlana had a PhD in economics, but had to help her husband, an engineer (also with a PhD) to sell homemade Barbie doll dresses on the black market. Under economic, political, and emotional stress, their marriage collapsed. Like millions of Russians, Svetlana found escape watching the glamorous American soap opera “Santa Barbara”. Feeling betrayed and looking for a better life, she placed a classified ad searching for a man who could help her to move to America. In her photobook, Markosian used the soap opera as inspiration, telling her family’s story through the perspective of her mother.

Markosian’s new book Father, as its title suggests, focuses on her father and her search to reunite with him after nearly twenty years of separation. When the Markosians moved to the United States, her mother cut the image of their father out of their family photographs. “For most of my life, my father was nothing more than a cut-out in our family album. An empty hole. A reminder of what wasn’t there.” Fifteen years later, Markosian travelled back to find him and began an attempt to reconnect.

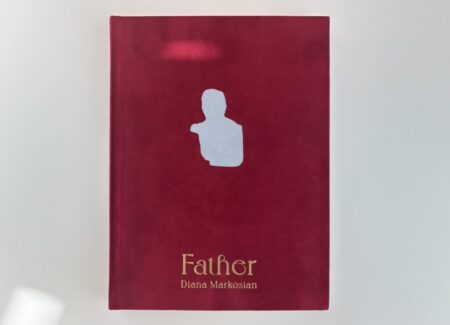

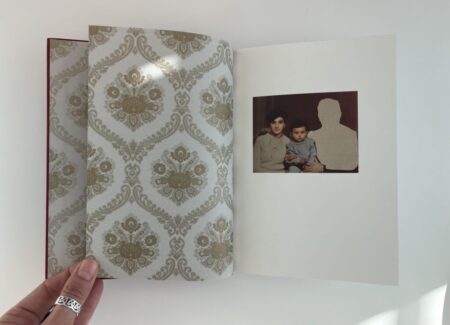

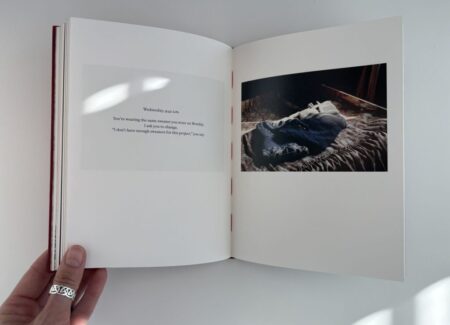

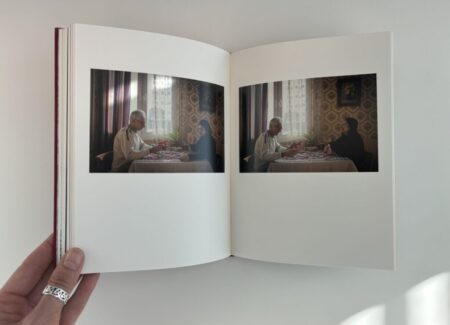

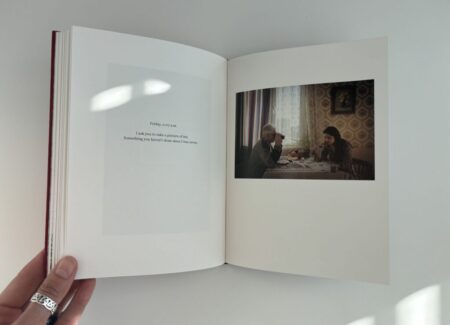

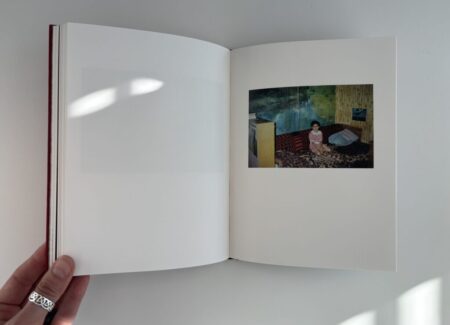

Father is a relatively small photobook with a red velvet cover. A silhouette in silver (the cut out of her father) is debossed in the center and the title and the artist’s name in gold are placed underneath. The book immediately feels both intimate and elegant. A pattern often seen in Soviet wallpaper is used for the endpapers, perhaps evoking the settings of the artist’s childhood. Inside, most of the images are horizontal and placed on the right side of the spreads, and occasionally certain images appear full bleed. The photographs are interwoven with short writings by the artist, guiding the narrative.

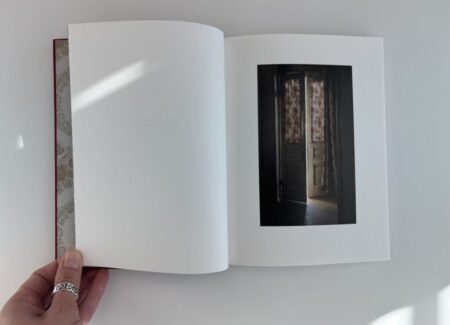

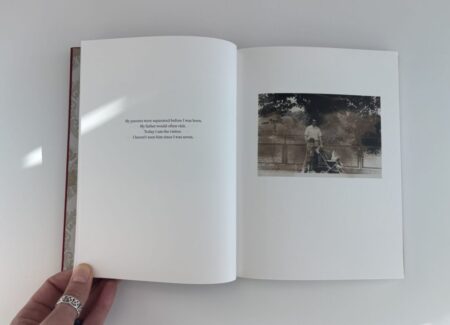

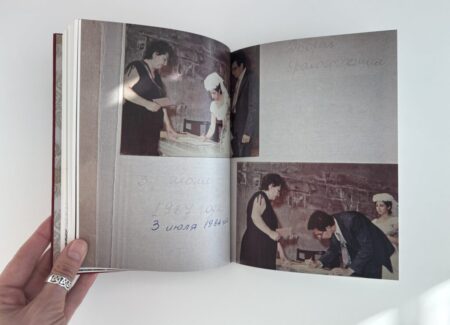

The book opens with a photograph of the artist as a young girl seated between her parents, but her father’s image is cut out, signaling displacement and absence. Old family snapshots (her parents signing papers at their wedding, her parents with a stroller, her young father holding a baby) allude to the wide gaps in their shared history, while more recent photographs, starting with a door slightly ajar, find Markosian ultimately spending time with her father once again, adding dramatic depths to their fragile and disjointed connection.

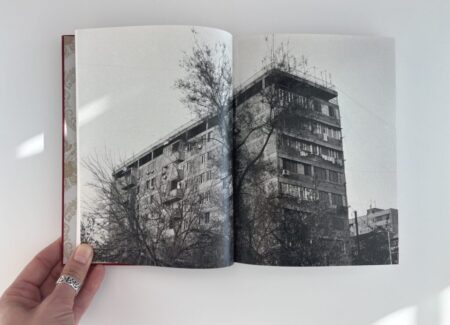

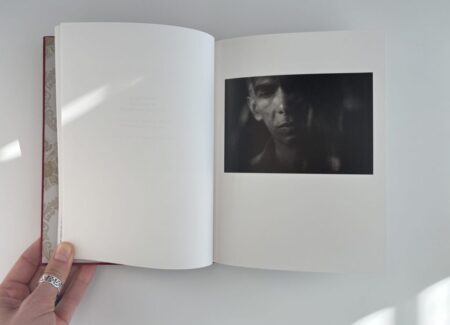

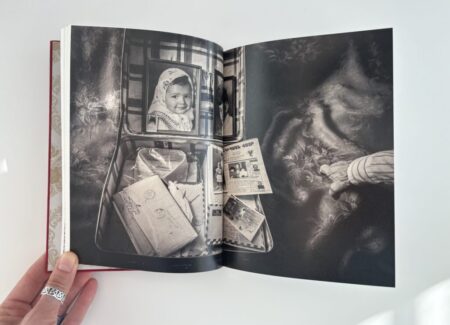

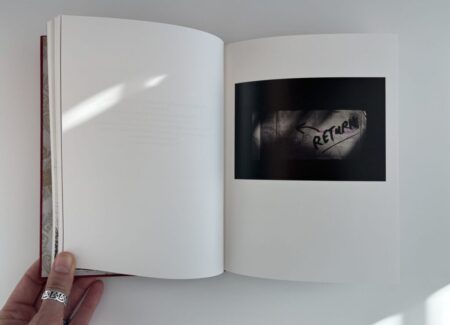

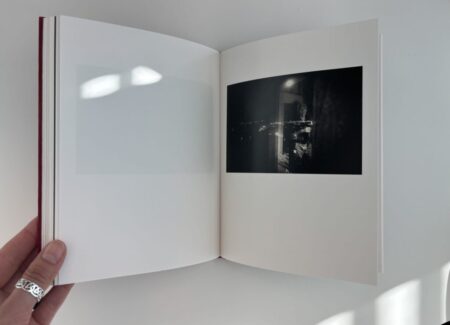

Using documentary photographs, family snapshots, and archival materials, Markosian sets out to map her journey of reuniting with her father, and this narrative unfolds in roughly chronological order. Fifteen years later, she visited his apartment; he didn’t recognize her, and at first, she didn’t recognize him either. His hair was now grey, his face gaunt. As she enters his apartment, she thinks about it as “a museum of her childhood”. Slowly they start to reconnect, and Markosian learns that her father was also looking for her. Over the years, he wrote letters to embassies, police stations, toy stores, and even random American addresses, looking for his family, as seen in a black-and-white full spread photograph that shows a suitcase full of letters, photos, and newspaper clippings. Another image documents one of the letters returned with the many stamps it collected, dramatically shot against black background. A selection of these letters is reproduced in the book, printed on a slightly lighter paper.

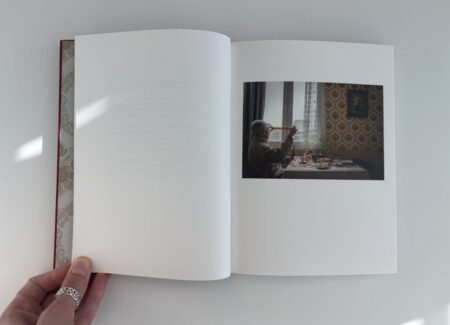

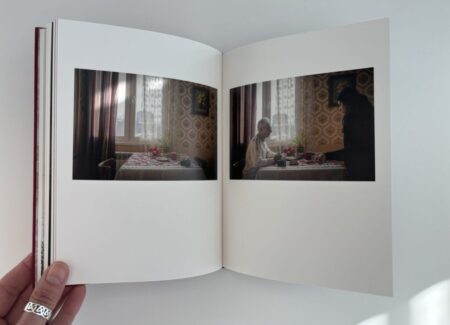

Father includes a number of photographs Markosian and her father made together, around his kitchen table, sharing a meal, playing card games, and chatting. One photograph shows her father taking a photo of her at the table reading a newspaper. She particularly asked him to take that one, noting that the last photograph that he took of her was when she was seven. These quietly intimate portraits capture a new phase in their relationship. “Reconnecting wasn’t immediate,” she reflects. “It was about building a friendship with a stranger, and grappling with the reality that we couldn’t reclaim those lost years.” The photographs in the project are not particularly remarkable on their own, yet the emotional story that brings them together makes the interaction with the book engaging and moving.

In recent years, a number of photobooks have looked back at various issues around family histories and archives. In her photobook Moisés (reviewed here), Mariela Sancari searches for her father (he committed suicide when she was a teenager) asking men in their 70s to sit for a portrait in her father’s clothes, creating a half documentary, half fictional journey to deal with her memories and grief. And the South African photographer Lindokuhle Sobekwa offers an intimately personal visual journey to recover the story of a lost sister in I carry Her photo with Me (reviewed here). Father is an excellent contribution to this kind of nuanced family conversation.

The book ends with the same photograph that opens it, only this time the father is included, symbolically marking the full circle of Markosian’s journey. Ultimately, Markosian turned her traumatic unanswered questions into a deeply personal photographic project. In this way, Father feels like an intimate diary or scrapbook, as we move through the artist’s family photographs, memories, and documents interwoven with her stories and reflections, which thoughtfully try to capture the hesitancy and vulnerability of the encounters with her estranged father, and even the uncertainty and difficulty in navigating this new relationship. Seen together, it is a compassionate continuation to her earlier project, in a way closing an unfinished chapter in her family story. A small envelope enclosed in the book invites readers to write a letter to a missing person in their own lives, acknowledging that her own story is part of the broader human desire for connection and reconciliation.

Collector’s POV: Diana Markosian is represented by Galerie Les Filles du Calvaire in Paris (here) and Rose Gallery in Los Angeles (here). Markosian’s works have little secondary market history at this point, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.