JTF (just the facts): A total of 14 black-and-white photographs, framed in light grey and unmatted, and hung against black walls in the front and rear spaces of the main gallery, as well as in the office area.

The following works are included in the show:

- 14 gelatin silver prints mounted to Dibond, 2023, each sized 44×55 inches, in editions of 6+2AP

- 1 two channel video with sound, 2023, 10 minutes 25 seconds, in an edition of 5+2AP

(Installation shots and video stills below.)

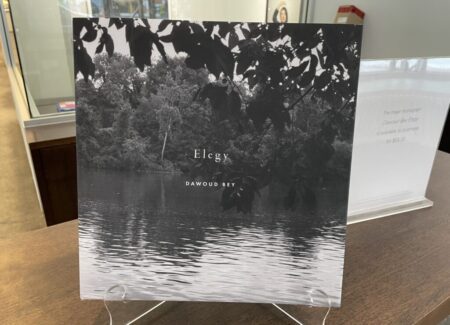

Images from this series were included in a monograph titled Elegy co-published by Aperture and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in 2023 (here, cover shot below.). They were also on view at the museum in 2023 (here).

Comments/Context: The walls of Dawoud Bey’s recent gallery show are painted black and the lights are turned off, creating the feeling of walking into a claustrophobic area of undefined darkness, punctuated by dimly spotlit photographs on the walls and a video running in the back. It’s a quietly disconcerting installation choice, deliberately filled with mystery and unease, making us unsure of what we might discover next, which is of course exactly the point.

The exhibit features Bey’s 2023 project “Stony the Road”, which centers on photographic landscapes he made near Richmond, Virginia, where African captives first arrived in the United States and were marched through the woods to slave markets. His photographs track that anxious, exhausting, and disorienting journey on foot, trudging down forgotten wooded paths through overgrown greenery, with little sense of what is happening or where the people might be going. In a sense, he is visually “reading” the contemporary landscape for visible traces of the past, finding evidence of the historical traumas of the American slave trade altogether present in the contours of the land today.

“Stony the Road” is the third part of a powerhouse trilogy of landscape projects Bey has been working on for the better part of the past decade. “Night Coming Tenderly, Black” provided the first installment in 2017 (as seen in Bey’s excellent career retrospective at the Whitney in 2021, reviewed here), and was similarly dark in its tonalities and tensions. In that project, Bey documented eerie nocturnal farmhouses with picket fences and enveloping thickets of nighttime forest in Ohio, each location a stop on the Underground Railroad heading north; the scenes felt charged with the simmering anxiety of escaping through dense forest, following directions to a lonely farmhouse, and carefully approaching a place that may or may not be safe.

This was followed by “In This Here Place” in 2019 (reviewed here), where Bey traveled to plantations along the banks of the Mississippi River in Louisiana, and documented empty slave cabins, overgrown sugarcane fields, and aging trees covered in hanging moss; in these images, Bey’s eye often pared down the available shapes to elemental geometries, and there is a physical sense of slow wandering along dirt roads, hearing the now silent voices that once populated these places.

“Stony the Road” completes the cycle, by turning back to the American lands where the slavery story began. Without knowing the harrowing backstory to Bey’s images, we might read them quite differently; on the surface, they offer sensitively seen black-and-white views of paths through thick overhanging forest, almost like the magical journey taken by two small children in W. Eugene Smith’s “The Walk to Paradise Garden”. Bey takes us down leaf strewn dirt pathways (or hints of pathways) along the river, where the grassy undergrowth and the canopy nearly merge, with foliage both reaching up and trailing down from above. His tactile images notice the details of these trees and plants, the layering of intertwined growth, and the dark silhouetting of overhanging leaves against the sky, intermittently adding momentary glimpses of the nearby river water through the trees, as though we were walking on foot.

Several pictures use the trail as a centering device, encouraging us to walk town the road ahead, with the surrounding landscape pushing in around us; given the age of some of these paths, most are faint traces of what they once were, like scars on the land that haven’t yet been entirely healed by nature. As the images circle the gallery walls, darkness and shadow come and go, the view from the path becomes increasingly blocked by walls of brush and greenery, the winding trails twist and turn (sometimes around blind corners), and thick tangled vines reach down like calligraphic marks or whitened thickets, blocking any view of the sky above.

With the truths of the Virginia slave trade as an understood backdrop, Bey’s photographs deliver a consistent dose of richness and complexity. Some 350000 men, women, and children were sold at the Manchester Docks in Richmond between 1830 and 1860, and so likely traveled down these very same dirt paths, having just emerged from harrowing months-long sea voyages. So when we look again at these dense forests, they don’t seem quite as hopeful or inviting; instead, we can imagine physically walking down these trails, hungry, emotionally exhausted, hot, disoriented, anxious, even dizzy, the greenery spinning around our heads as we follow the crowds, search for family members, and try to understand what might come next in this very unfamiliar place. Bey’s haunting photographs feel remarkably present, with the surroundings continually close in, making our own contemporary journey feel all the more threatened and confusing. In his hands, these faint traces of traumatic history come alive, with ghosts seemingly still walking along these now deserted paths.

As he has increasingly done in recent years, Bey has also made a short film with this same Virginia slave trail material (titled 350,000), bringing motion and sound to the pathway scenes and creating a more immersive experience of what it felt like to walk along those leafy trails as a recently disembarked African. Aided by cinematographer Bron Moyi, Bey has crafted a two-screen back-to-back installation that offers two walks down the same stretch of path, like two individual experiences of the same road as seen by separate people. The camera seems to float at roughly chest or eye level, making the scale feel essentially life-sized, and the swirling walk down the road is seen as a single take, with no breaks, cuts, or stops to the visual flow. While the still images on the gallery walls capture distinct places and specific resonant moments, the film is altogether more loose and intimate, with the camera tracing the turn of a head as it looks up into the sky, down the path, into the greenery off to the sides, and through pockets of openings to the nearby river, in a constantly moving sweep that drifts in and out of focus, depending on the space being observed, almost mimicking a kind of dazed stumbling and wonder at the foreignness of the surroundings.

The understated soundtrack to this visual journey is particularly powerful. Made in collaboration with E. Gaynell Sherrod, the sound starts with audible breathing, intermingled with the sounds of chirping birds, buzzing insects, and leaves rustling in the wind from the immediate surroundings, immersing us in an auditory environment filled with the sound of bodies moving. As the film progresses, the breathing becomes more labored, and heartbeats thump along, making it clear that the walkers are becoming tired by the effort required to move. Intermittently, even more sounds flit in and out: grunts, the clop of horses, sighs, the clinking and dragging of chains, and even some low humming, whispering, and singing of songs/spirituals, the trudging and breathing becoming almost rhythmic. As the visuals move through space, looking here and there along the line of the trail in a kind of fog, so do the sounds, giving presence to the otherwise invisible people who made this harrowing journey.

In all three of Bey’s projects, he has taken the conceptual position that the land (or the ground itself) holds and communicates memories, and that if he is patient enough to attentively observe and listen, it will reveal its histories and the enduring presence of ancestors. Like Sally Mann’s haunting images of Civil War battlefields, Bey’s meditatively brooding photographs (and films) excavate the past and act as contemporary witness to its overlooked traumas. In revisiting these historical sites, he is, in a sense, deliberately and purposefully re-envisioning them, seeing them anew through the lens of the past and re-establishing them as places of remembrance and reflection. This process of compassionate re-engagement doesn’t dilute the agonies that he finds in these locations, but amplifies their now faint resonances so we can better hear (and see) them. “Stony the Road” is a fitting endpoint to his three-part project, returning us to the very beginning of the Black experience in America and asking the land itself to be a truth teller.

Collector’s POV: The prints in this show start at $35000 and then rise in increments of $5000 as the prints sell. The video work is priced at $80000. Bey’s work has only begun to surface in the secondary markets in recent years, with prices for the few lots that have sold ranging from roughly $2000 to $51000.