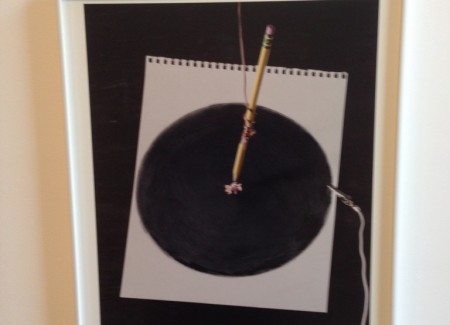

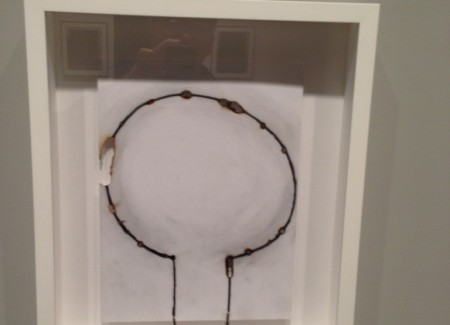

JTF (just the facts): A total of 41 photographs (17 gelatin silver prints; 22 archival pigment prints), framed in black wood and matted, and shown against grey and white walls in the East and West rooms of the gallery. The West room also features a single work of 15 archival pigment prints arranged as a 5×3 grid, as well as 7 graphite on paper prints, framed in white wood and matted; these unique pieces might perhaps better described as sculptures, with snippets of wire attached by alligator clips to paper that has been singed or scarred by electrical current. Prints are in editions of 9 with 3 artist’s proofs. All works date between 2010-2013. (Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: With an MFA from the Visual Studies Workshop and a Masters in molecular genetics from Harvard, David Goldes has no trouble bridging the divide—one that widened in the 20th century—between art and science. In this, his fourth show at Milo, he has drawn on this dual upbringing to take us back to the late 18th-early 19th century when a group of geniuses in physics and chemistry were discovering the principles behind electricity and photography.

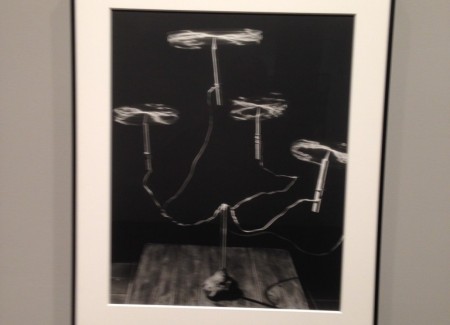

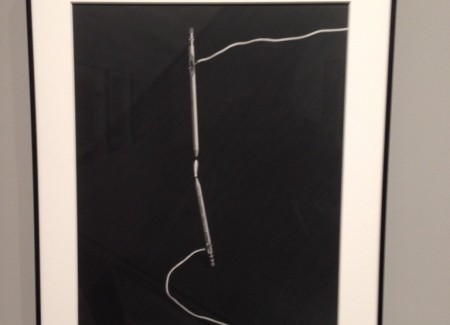

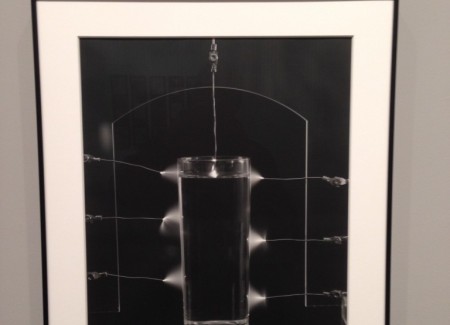

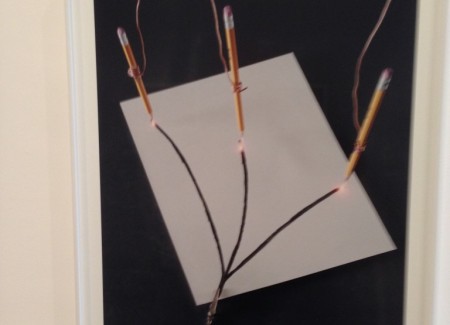

Goldes’s series of “Electro-graphs” are table-top experiments, staged for the camera in a darkened studio, that demonstrate some of the natural laws of conductivity and electromagnetic induction. Applying these laws to a handful of materials—water, copper, steel, graphite, thread, and paper—he generates light, moves objects, charges filaments, and sets paper ablaze. In each case he makes a picture that is only partially under his control.

The results are like an episode of “Mr. Wizard” shot as a low-budget film noir, or arte povera without the theoretical rodomontade.

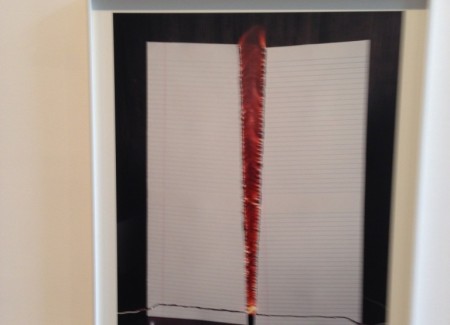

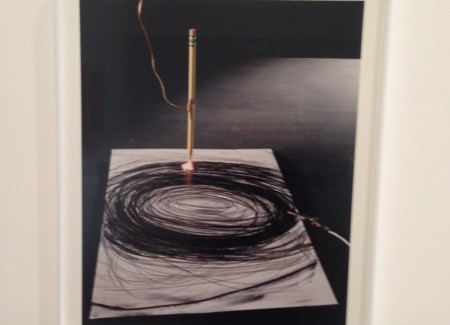

“Charged wires spinning and balancing on exacto knives” (2012), for instance, is precisely what the title declares: it’s a photograph of four straight wires, shot full of electric current and set awhirl like silver helicopters or a family of dragon flies against a dark background. “Spiral drawing, pencil and electricity” (2012) is a picture of a picture: a wired-up yellow pencil, attached to an unseen power source, has been spun in circles so vigorously that it has produced a thick graphite scrawl. In one of the show’s stand-outs, “Jacob’s ladder on lined paper” (2013), a spark has jumped between two electrodes and ignited a piece of notebook paper—a reminder that electricity has an inflammatory nature, even if the modern system of circuit breakers allows us to forget this.

Many of Goldes’s photographs are like magic tricks that taunt viewers to figure out how he performs them. I can’t figure out why the pools of light in “Electrified Nail” (2012) should have formed this particular array (and not some other) around the shaft and top of this penny nail. The science behind “Static electricity driving spinning wires up the incline” (2012) is textbook; that static electricity could do mechanical work was news to me.

Hiroshi Sugimoto has recently exhibited a similar fascination with the sublime beauty of electricity. The massive voltages of Van de Graaff generators can produce fiery displays guaranteed to scare and thrill audiences, as James Whale proved in the 1930s with the Frankenstein movies.

But the fustian manner of Sugimoto in this 2008 series, with installations and prints far too grand for their ultimate effect, turns the science into crowd-pleasing entertainment. (If they were Las Vegas acts, Sugimoto’s would be like David Copperfield’s, Goldes’s has the cunning modesty of Ricky Jay’s.)

Goldes’s photographs share the investigatory attitude about the conventions of photography and pictures found in Zeke Berman’s blackboard and table-top still-lifes from the 1980s, and in Abelardo Morell’s “Lightbulb” (1991), his classroom illustration of the physics of light and cameras. Robert Cumming’s puckish backyard scientific trials from the ‘70s may be predecessors as well.

Richard Holmes, in his magisterial history “The Age of Wonder: How the Romantic Generation Discovered the Beauty and Terror of Science,” recreated the era when English poets and scientists spoke a common language based in an almost religious awe toward the natural world. Coleridge, Wordsworth, and Shelley made it their business to stay informed about the latest advances in astronomy, chemistry, physics, and electricity and were inspired by their friendships with William and Caroline Herschel, Humphrey Davy, and Michael Faraday.

With photographic advances during the latter decades of the 19th century, scientists such as Hermann Schnauss were able to capture startling images of electricity—sparking off brass gauges or haloing around a human hand. The release of these photographs, as Corey Keller argued in “Brought to Light: Photography and the Invisible 1840-1900,” helped to soothe the nerves of the public, which was thoroughly acquainted with the destructive potential of lightning: they knew it could strike them dead in a thunderstorm or burn their homes. Utility companies needed to overcome these fears in order to wire customers into power grids. Seeing electricity in a photograph, acting on human bodies and leaving them unharmed, helped to demystify and domesticate this invisible force.

Goldes helps to restore some of the primal wonder (and danger) found during the Romantic period when science first learned to harness the energy of light, for electrical power and for photography. With the plainest of means, he illustrates natural laws that were first discovered more than a century-and-a-half ago and that for him clearly have not lost their ability to enchant. What Faraday wrote in 1858 applies to Goldes’s smart and sophisticated body of pictures as well: “I am no poet, but if you think for yourselves, as I proceed, the facts will form a poem in your minds.”

Collector’s POV: Prices for the gelatin silver prints begin at $3500, while the the archival pigment prints start at $4000. The unique pieces (graphite on paper with wire) sell for $5000. The 15 prints that make up the grid are available either individually for $2500 each or as a group for $35000. Goldes’ work has very little secondary market history, so gallery retail remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.