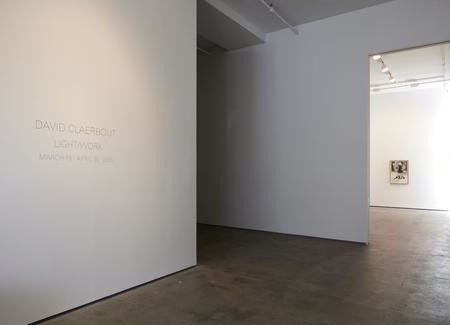

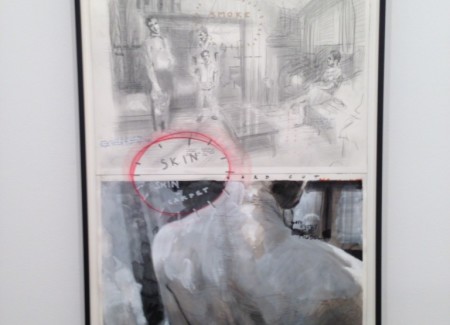

JTF (just the facts): A total of 20 works displayed on two floors of the gallery. On the street level are 15 drawings (washed ink, felt pen and pencil on paper), framed and matted. Thirteen of these are in the Northeast space; two are in the director’s office. All date from 2015. Elsewhere on this floor are two single-channel video projections, with HD animation (one in color, dated 2013; the other in black-and-white, and dated 2015-16.) Both are silent and issued in an edition of 7 with 1 AP and 1 AC. There is also a two-channel video on 19-inch flat screens, silent, color, dated 2013, and issued in an edition of 5 with 1 AP and 1 AC; and a two-channel video installation, with HD animation, color, stereo sound, dated 2016 and issued in an edition of 7 with 2 APs and 1 AC. Playing in a room below street level is a 12-minute single-channel video, with HD animation, color and stereo sound. It dates from 1996-2013 and is issued in an edition of 7 with 1 AP and 1 AC. (Installation shots below, several courtesy of Sean Kelly Gallery, photographs by Jason Wyche.)

Comments/Context: David Claerbout’s installations switch so seamlessly between still and moving images that it can take a few minutes to figure out what’s going on. Are we watching a slow-motion video? Or a single photograph that a camera, attached to a software animation program, is painstakingly moving over and around? Is he an artist for whom discriminations between video and photography are trivial? Or is his view of technology utopian, his work designed to unify the two experiences of time, as flowing and stopped, into an endless collection of potentially blissful moments?

For his first solo exhibition in New York since 2008, the 46-year old Belgian artist (based in Antwerp) has chosen recent work that refers specifically to people and places on three continents—Africa, the U.S., and Europe—as well as to the act of traveling through them all.

Dividing the main space of the gallery is a scrim on which is projected a color photograph of perhaps 40 men and boys standing beneath a concrete overpass. The title, Oil Workers (from the Shell company of Nigeria) returning home from work, caught in a torrential rain, locates the scene.

Claerbout found the image on the Internet and was struck that someone would have taken and posted a photo of anonymous workers patiently waiting out a storm. The crowd faces the camera. But with the use of 3D graphics, he has altered the perspective so the bodies of the men have solidity. As the camera weaves around the scene, characters appear or disappear from the edges of the frame. While this technique offers the illusion they are grounded in a particular space, it also mocks the impotence of their inaction by putting them at the mercy of a slippery and nosy computer program. The piece is thus, unfortunately, more about him and his clever software than about them.

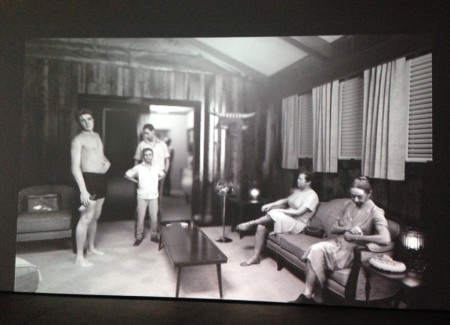

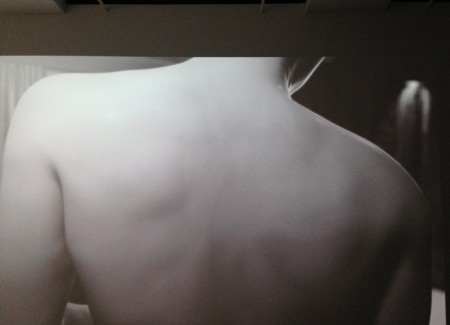

A far smarter application of 3D graphics can be found nearby in KING (after Alfred Wert-heimer’s 1956 portrait of a man named Elvis Presley). This time Claerbout has chosen a black-and-white documentary image by the German-born Wertheimer, who recognized before any American photographer what the “Hillbilly Cat” was becoming. A shirtless Elvis stands in a wood-paneled suburban room beside members of his family, as Claerbout’s camera prowls around the photograph with the obsessiveness of a fan, examining close-up the 21 year-old’s pale naked flesh, stopping to isolate the open mouth of a Pepsi bottle he holds in his hand. Wertheimer’s photographs are undeniably homoerotic, and Claerbout’s funny, lubricious take on the beautiful young man who would be King illustrates both the singer’s guilelessness as well as his raw sexual magnetism—a uniquely American energy that has turned on countless fans and musicians (R.I.P. Prince.)

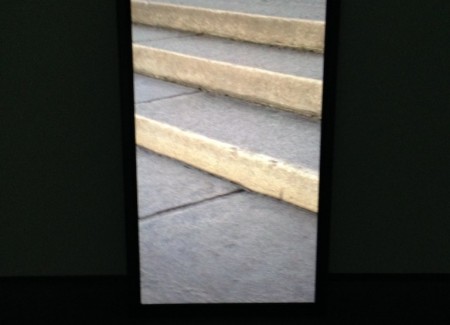

Claerbout’s newest video projections, Olympia (the real time disintegration of the Berlin Olympic stadium over the course of a thousand years) is a computer-graphics reconstruction of the Nazi masterpiece built by architects Werner and Walter March for the 1936 Olympic Games. Claerbout has modeled his virtual building on the actual one, as it exists in 2016, reproducing each stadium step and patch of grass.

The camera crawls around the empty spaces below the stands. While it may appear as if nothing in the scene is changing, the piece is designed so that the computerized structure will slowly disintegrate over the course of 1,000 years (currently it is programmed for the next half-century.) This longue durée view of time is fitting for a piece about the folly of empires—Hitler believed that his leadership would begin Germany’s Thousand-Year Reich—and the far longer lives of buildings in stone.

Claerbout’s video has affinities with other millennial-related art and music projects. John Cage’s Halberstadt Organ Project (2001) is a musical piece programmed to be completed in 639 years. This is less than the blink of an eye compared to Rodney Graham’s Verwandlungsmusik (1991), which consists of a looped phrase by Wagner’s friend, Engelbert Humperdinck, designed to play over 39 billion years. (Graham has helpfully provided shorter versions in a book and a CD.)

Claerbout’s video Travel, playing in the lower-level gallery, lasts only 12 minutes but they feel like an eternity. The camera ambles along a forest path, beside rushing streams, looking forward through archways of trees, toward a destination that is continually beyond. The 3D simulations of Nature did nothing but inspire me want to head outdoors in search of the real thing.

Patience is required with Claerbout’s work, and is usually rewarded. I remember visiting a Madrid gallery in 2009 and happening upon his video Sections of a Happy Moment (2007). Based on visual material notable only for its featureless banality—inside a clean and modern housing complex, three generations of a Chinese family stand in the courtyard, watching a child throw a ball into the air—the piece is another photographic deconstruction. But as the camera presents each person and grouping from multiple angles, the family unit gradually seems far stronger than the sum of the individuals. The piece is about latent possibilities—for simple joy, above all—that are seldom grasped as they happen. The black-and-white family drama unfolds silently over 25 minutes. I sat through it twice.

When he finds the right images to expand upon, and he locates what T.S. Eliot in one of the Four Quartets called “the still point of the turning world,” Claerbout can be a restorative artist. It’s frustrating then that most of the works in his latest show do more to test the attention span than to repair the soul.

Collector’s POV: The works on view are priced as follows. The drawings range in price from €10000 to €15000 while the film/video works range from €50000 to €125000. Claerbout’s photographic work has not had much secondary market exposure in recent years. A handful of lots have changed hands, at priced ranging from roughly $2000 to $25000, but this data may not be entirely representative of the market for his best work.