JTF (just the facts): Published in 2018 by Kodoji Press (here). Softcover with 288 pages, includes 399 color and 27 black and white plates. Texts by Walter Benn Michaels. In edition of 1000 copies. Design by Winfried Heininger and Daniel Shea. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: By their very nature, large cities are in a constant state of flux, and a complex and sprawling metropolis like New York City continues to change and expand year after year, responding to a never ending stream of urban demands. In the past few decades, industrial, gritty, and previously unsafe parts of the city have been reborn as trendy neighborhoods, and increases in income inequality and hyper-gentrification have pushed some of New York’s creative energy and diversity further toward the outskirts. Property developers and well-off families are often the ones who drive these kinds of top-down transformations, as investment-driven improvements and subsequent rent increases make it harder for longtime residents and businesses to stay in their existing neighborhoods.

Rapid construction and new developments are at the center of 43-35 10th Street, the newly released phobobook by artist Daniel Shea. Shea is based in Long Island City, his home since his move from Chicago five years ago. Located on the waterfront of East River in the borough of Queens, and just one subway stop from Manhattan, LIC is being dramatically reshaped by the latest real estate boom, and Shea has become an active observer of how the local urban landscape is changing around him.

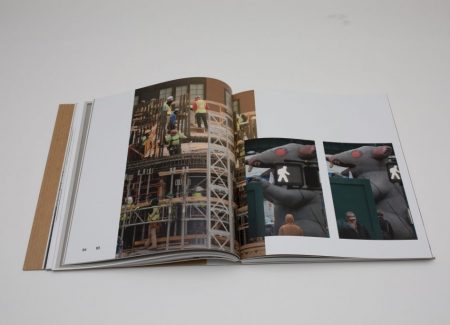

The title of the book, 43-35 10th Street, refers to one specific building in Long Island City (the artist’s home and studio), yet Shea goes beyond that single address, building a multi-layered narrative that asks questions about politics, class boundaries, and the true beneficiaries of the changes taking place in the neighborhood. The large-scale construction projects popping up here and there are bringing an influx of new jobs and renovations, but labor disputes and tensions between workers and unions are found on the other side, together with growing economic inequality. The old industrial area populated by movie-production facilities, warehouses, factories, and bakeries is quickly shifting from a forgotten urban blight to a new hot destination.

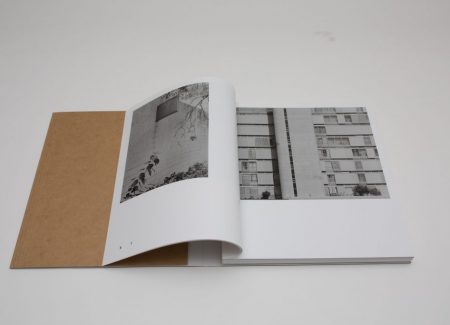

Shea doesn’t just document these ongoing transformations, he offers perspectives to consider them in a wider context. Black and white photographs of the architecture of Brasília serve as an introduction to the book. Brasília was planned from scratch, a city of dreams, built in the 1960s on an empty plateau in the middle of nowhere. It was invented by politicians and bureaucrats, with functionality taking priority over natural and spontaneous human order. A showcase for Brazilian modernism, it was designed by the architect Oscar Niemeyer and the urbanist Lúcio Costa. It had clean lines, rational planning, and a huge amount of space, preparing the city for an automobile-filled future. The concept of the city also tried to incorporate the issues of social equality, but in reality, working class residents were forced to the outskirts of the city, in a far less organized manner. Photographs of the government buildings of the Brazilian capital, very precise and refined, appear throughout Shea’s book, creating an architectural dialogue with the ongoing construction taking place in Long Island City.

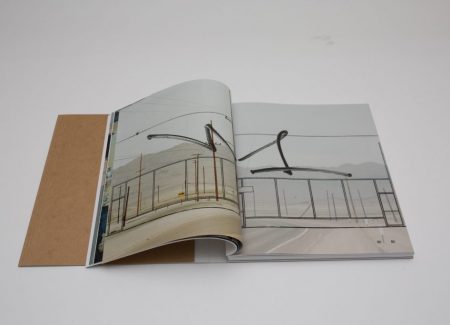

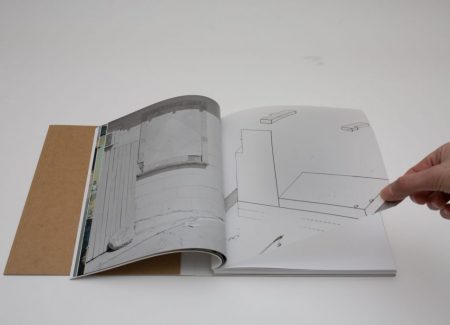

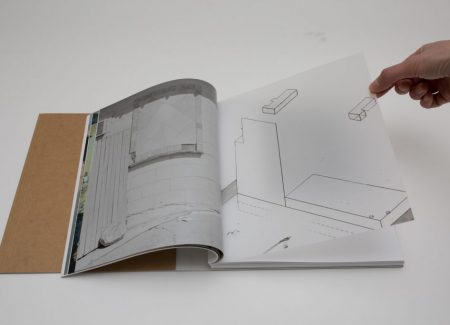

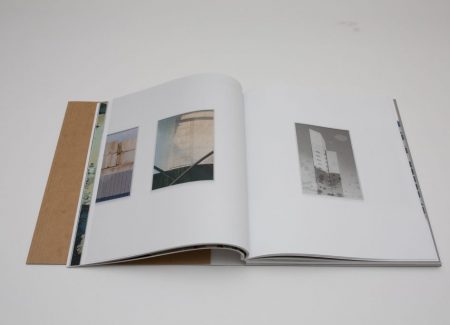

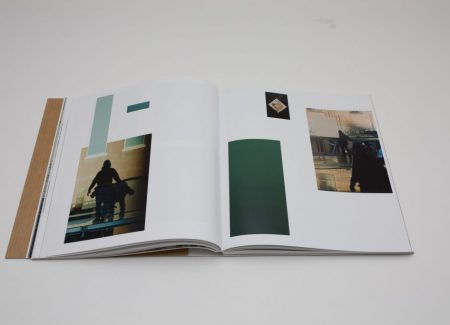

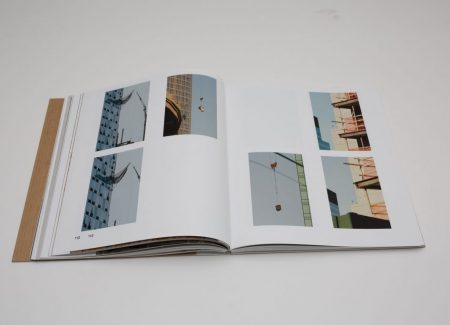

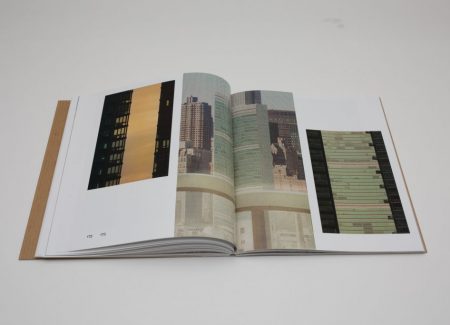

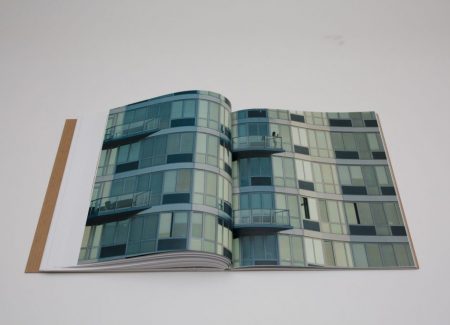

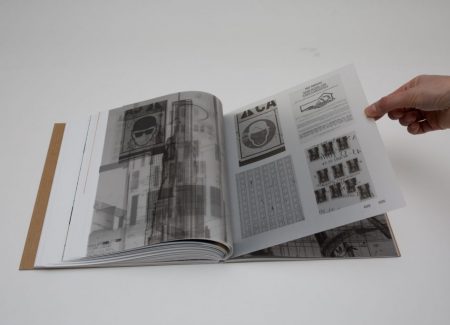

As a photobook, 43-35 10th Street is an elegantly crafted object – well conceived and thoughtfully designed. Its light brown cover has an image of bird in the upper right corner, and opens as a flap, revealing a formal shot of a sofa and a coffee table. Throughout the book, the photographs vary in size, and Shea continually experiments with placement and page layout: full spreads, overlayed shots, multiple photos on one spread, as well as images continuing from one spread to the next one. The organization of the images is meticulous, the precise sequencing constructing his narrative, creating layers of unexpected connections and exciting juxtapositions. The supplementary text is printed on grey paper, these pages standing out as a distinct element of the book.

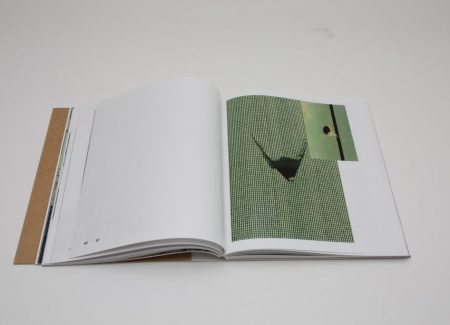

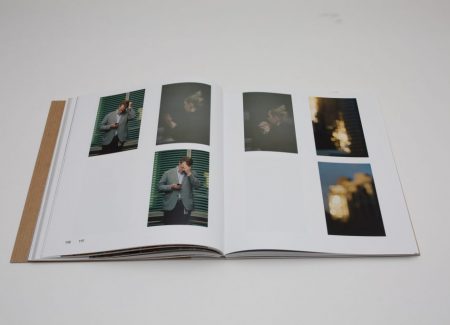

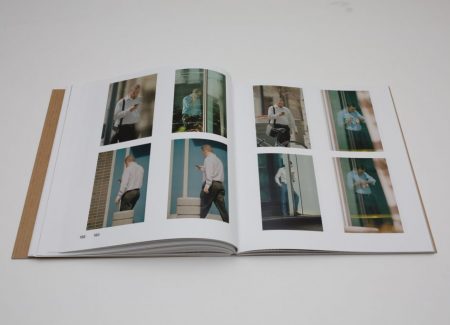

Shea’s photographs are strongly formal, focusing on composition, color, line, and shape, with images of construction details getting close up to walls, pipes, bricks, windows, parts of building elements, fabric, and various surfaces. One spread shows a selection of diamond or square-shaped viewing panels cut into fences, used to show the progress of the construction (they are required by NYC law). Abstract and geometric shots like these are followed by images of construction workers in action, busy installing and moving things. The tension between industrial elements and the natural world is reinforced by fragmentary views of nature, through shots of isolated leaves dropping shadows, and close-ups of ponds, rocks, and birds. Occasional photographs of men and women in professional business attire, often busy on their phones, provide an obvious contrast to the construction sites and the people working there. And the utopian element of construction dreams is captured through images of pristine advertisements for new luxury condo buildings.

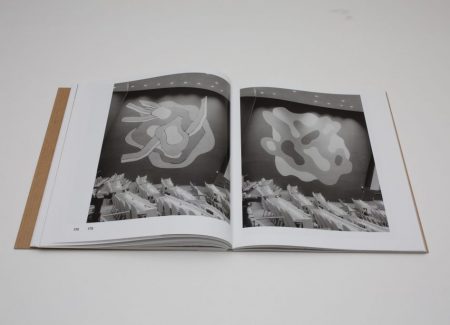

Shea also experiments with superimposition, as he pursues his interest in seeing one thing through something else. Architectural sketches printed on transparent paper are layered over landscapes, creating a back and forth between the project presented on paper and its reality, as well as the relationship between human invention and nature. Another image superimposes the plans for a luxury condo directly on Shea’s photograph of Niemeyer’s National Congress Building. Throughout the book, Shea also inserts colored shapes, sometimes covering part of an image or just positioned next to it, the fragments serving as both building blocks of his narrative and intriguing interruptions or tangents.

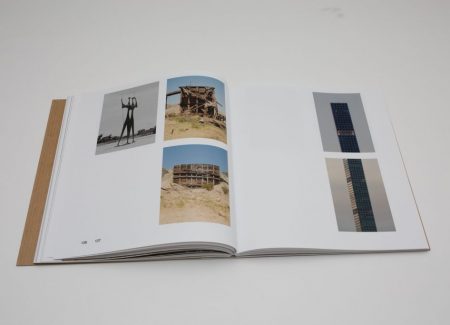

One of the most exciting spreads is close to the middle of the book. It brings together a black and white photo of Bruno Giorgi’s monumental sculpture known as Os Guerreiros (The Warriors), erected to pay homage to the thousands of workers who built Brasilia. Next to it, there are two shots of wooden ruins in a desert. The two vertical images on the edge of the right page depict a residential skyscraper on 57th Street in Manhattan, the third tallest building in the United States. The disparate elements connect ambitious ideas with more humble implementation realities. A few pages later, recognizable images of the glass facade of the United Nations building are followed by a spread with black and white interior photos of the UN General Assembly Hall, reinforcing the Oscar Niemeyer connection begun earlier.

Shea’s 43-35 10th Street is complex and clever photobook, defining Shea both as an artist with a distinct photographic vision and aesthetic, and as an intelligent researcher masterfully integrating multiple connections and allusions as part of constructing his larger narrative. In assembling this multi-layered portrait of a neighborhood in transition, Shea examines the ambiguities and politics of urban development, while also allowing for elements of visual poetry and mystery. As a sophisticated artistic statement in book form, 43-35 10th Street is one of the strongest photobooks published this year.

Collector’s POV: Daniel Shea is represented by Webber Represents in New York and London (here) and Andrew Rafacz in Chicago (here). His work has not yet found its way to the secondary markets, so gallery retail remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.