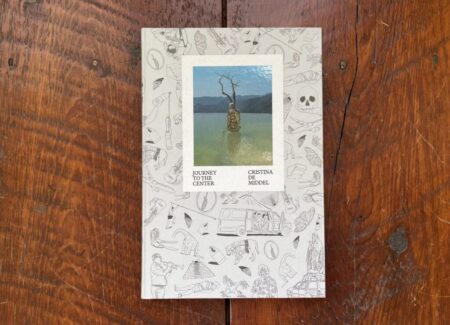

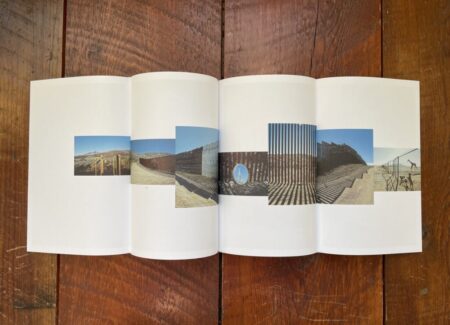

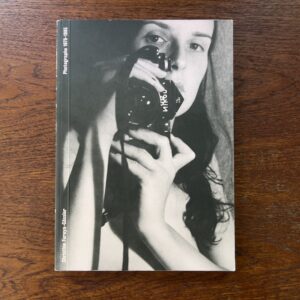

JTF (just the facts): Co-published in 2024 by Editorial RM (here) and Editions Textuel (here). Hardcover, 7.9 x 11.8 inches, 176 pages, with 150 image reproductions and 5 multi-image fold outs. Includes an essay by Pedro Anza, interviews conducted by the artist and other notes, an annotated image list, and quotes from Jules Verne (in English/French/Spanish), with full Spanish translations available on a loose insert. Design by Maricris Herrera. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Published in conjunction with an exhibition at Rencontres d’Arles in 2024 (here).

Comments/Context: Back in 2015, the Spanish photographer Cristina de Middel was driving around southern California between assignments, and on a lark decided to drive down to the town of Why along the Arizona/Mexico border, simply because of its questionable name. On the way, she saw an exit off Highway 8 for the town of Felicity, the self-proclaimed “Center of the World”, and couldn’t resist a quick serendipitous detour to see what such a preposterous claim in the middle of the desert might actually involve.

As it turns out, both the so-called town of Felicity (which was named after his wife) and the complex of structures at the Center of the World (which includes a pyramid, a church, the Museum of History in Granite, and other attractions) are the work of one Jacques-André Istel, a dreamer of sorts, now in his 90s, whose resume includes both investment banking and parachuting (as the “father of American skydiving”.) And while this character and his exploits piqued de Middel’s curiosity, her encounter with the Center of the World became the catalyst for her own artistic imagination, keying off the connection between the place’s ambitious title and the famous adventure story Journey to the Center of the Earth by Jules Verne. What if the hot button social and political issues of borders, refugees, and global migration were seen from a different angle, she thought, with migrants as the heroes in their own adventure stories instead of faceless masses or unwanted trespassers? And what if their astonishing journeys of hardship and endurance weren’t aimed at making it to the United States in general, but to this potentially magical place across the border called the Center of the World?

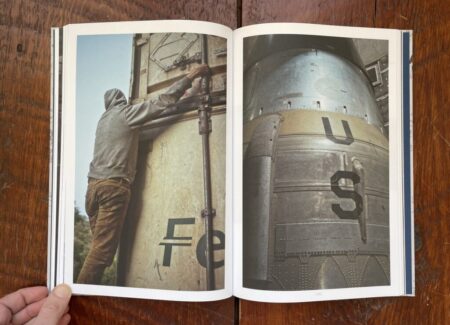

This fantastical reconsideration of the current immigration narrative ultimately became the underlying framework for a multi-year, multi-layered study of the migration route from Tapachula near Mexico’s southern border with Guatemala (and back even before that from many to starting points further south) to crossings into the United States from the Mexican state of Sonora, a distance of more than 2000 miles. Along the way, de Middel traveled with migrants on the northbound train nicknamed La Bestia (“the beast”), interviewed a broad sample of families, drug cartel enforcers, thieves, police officers, humanitarian volunteers, van drivers, and smugglers (“coyotes”), and patiently listened to the individual stories they all had to tell.

What has always separated de Middel’s work from that of her contemporaries (particularly her fellow photojournalists) is her liberal merging of documentary truths and observations with elements of the surreal, the magical, the ghostly, and the spiritual, which are often photographically staged, or at least encouraged. De Middel first burst onto the photography scene back in 2012 with her self published photobook The Afronauts (reviewed here in a 2013 gallery show), which playfully re-imagined a mid-1960s effort by Zambia to build a space program; her images of figures in improvised space suits felt like a playfully aspirational fairy tale, although the story was rooted in actual history. In the decade since, she has been busy with commissioned work, personal projects, and photobooks (as well as a stint as the president of Magnum Photos), crisscrossing the globe and continuing to creatively blur the lines between fact and fiction in her visual storytelling.

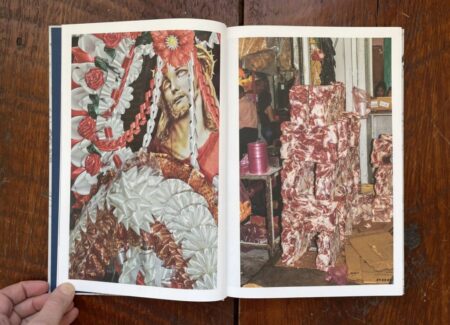

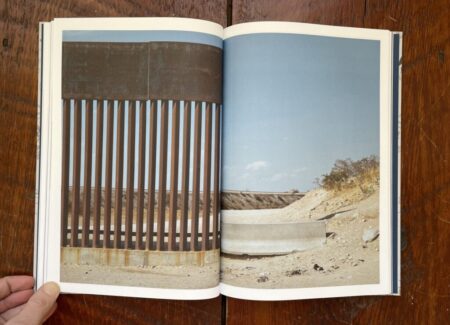

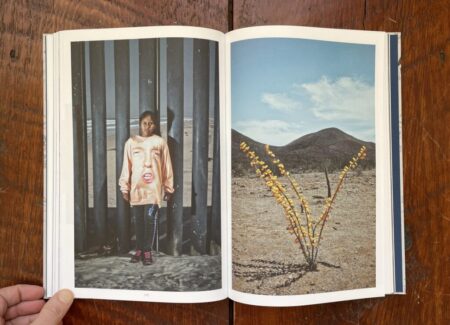

Journey to the Center brings together a sophisticated (and lengthy) mix of image making approaches. Some of the photographs are of course straightforward documentary views of people, places, and things along the route of the migration journey, which provide factual evidence or historical context for the larger narrative de Middel is constructing, with the artist’s extensive text captions gathered at the back of the photobook helping to fill in the connective logic behind their part in the larger migration arc. Other images start with these same available elements, but compositionally isolate and frame the photographer’s discoveries with an eye for the strange or unexpected; we can still categorize these pictures as documentary truth, but they’ve got much more artistic flair and found oddity in their aesthetics.

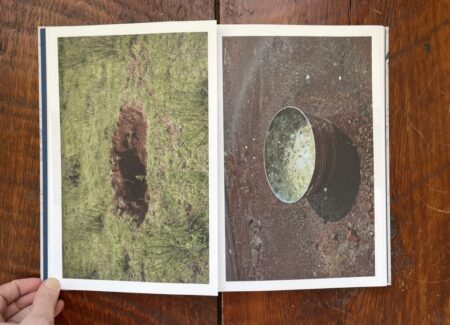

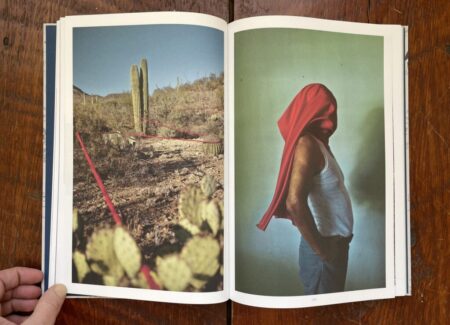

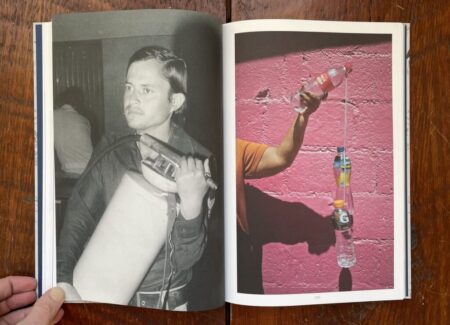

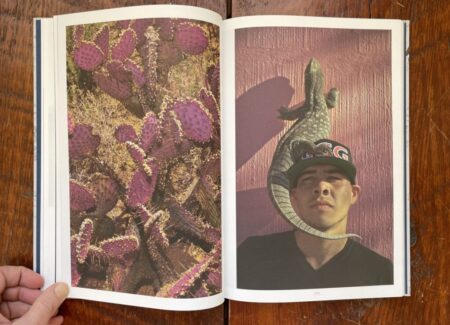

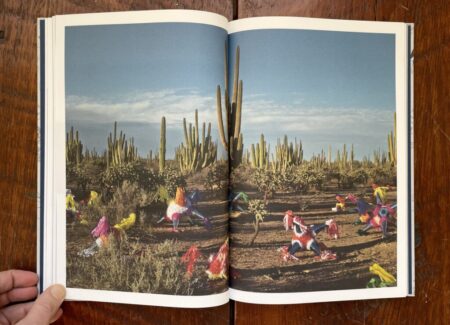

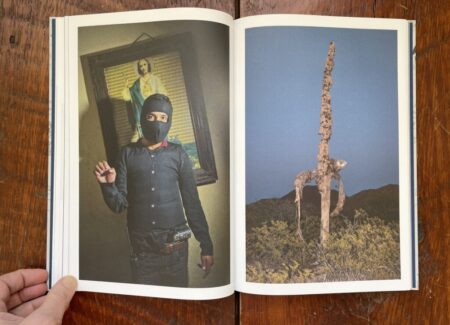

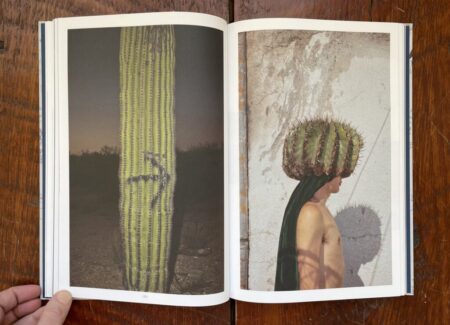

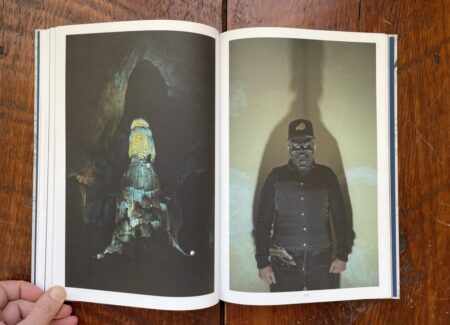

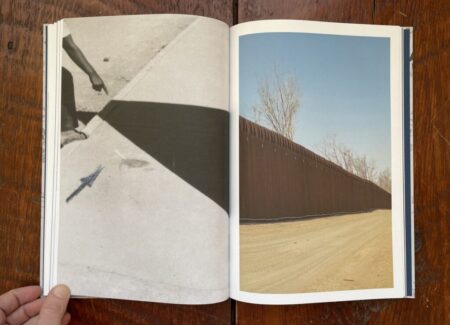

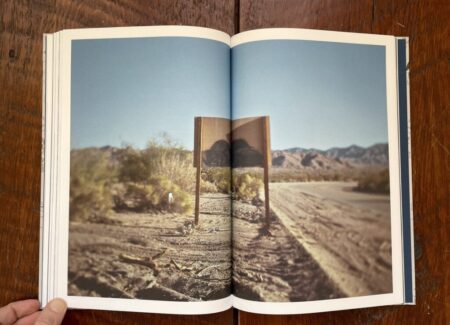

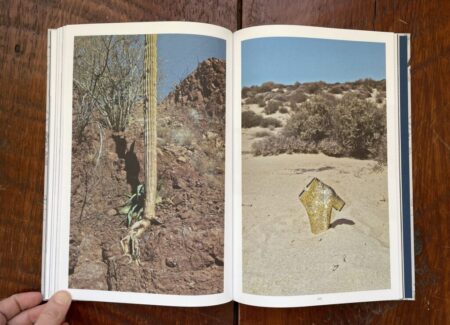

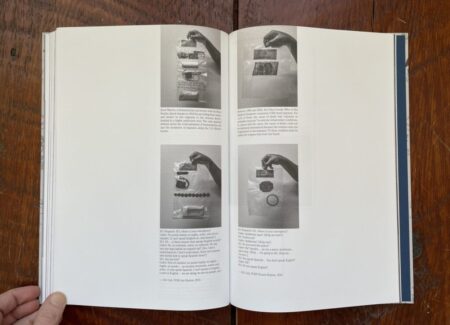

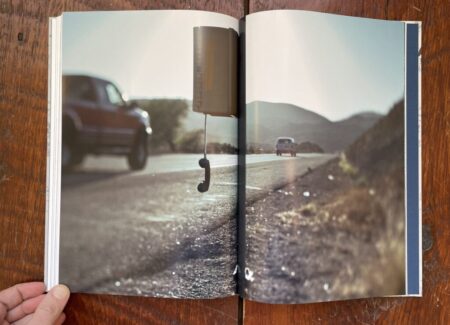

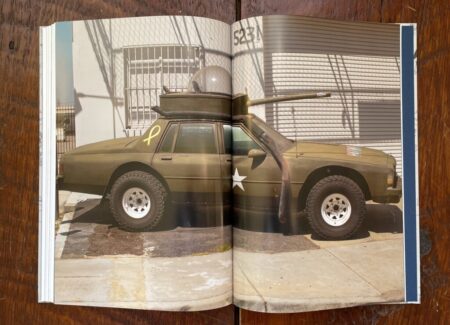

Active posing then enters de Middel’s visual vocabulary, ranging from dramatic setups involving masks, shadows, gestures, costumes, and other props (including an iguana on the head as an homage to Graciela Iturbide and a dog wearing boots fitted with machete blades) to fully staged events, like the athletes trying to pole vault over the border fence or doing the splits across the demarcation line. De Middel has also made a number of physical interventions in the desert, in the jungle greenery, or near the border, with colorful piñatas, stretched ropes, a sparkly gold boot, a round mirror, a Norman Rockwell plate, and some orange cheese puffs. To these she then adds archival black-and-white images found in Mexican thrift store albums and sober still lifes of bagged personal effects from dead migrants, ultimately bringing together a tidy half dozen photographic approaches to tell individual parts of her larger story.

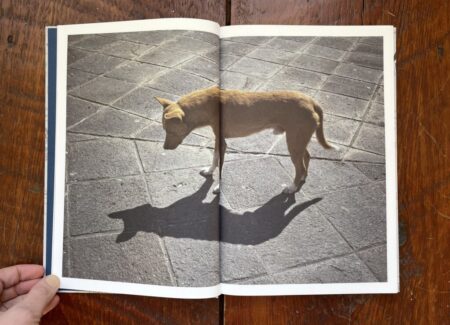

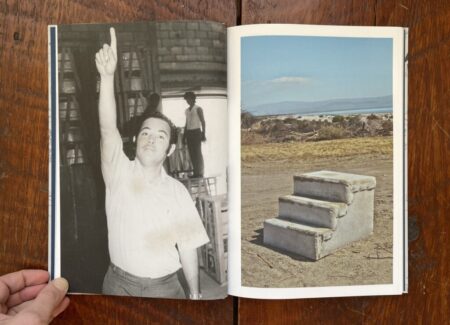

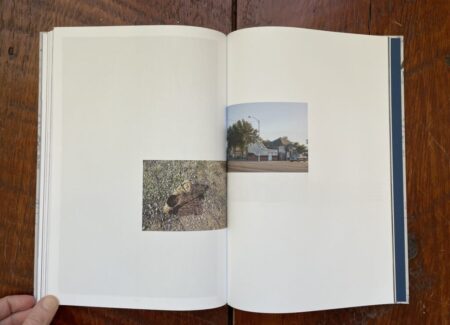

The design and construction of Journey to the Center as a photobook object actively blend these many visual ideas, mixing the various image types together into one integrated flow, where documentary truth and improvisational interpretation freely intermingle. Most of the spreads feature two vertically oriented images (with thin white borders) or one horizontally oriented image crossing the gutter, with the archival black-and-white images presented full bleed (without borders) to set them apart just a bit; small numbers underneath some of the pictures lead back to the detailed annotations in the rear of the book.

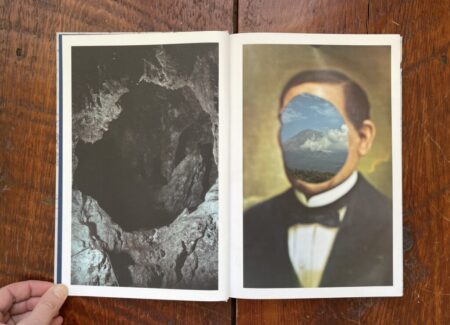

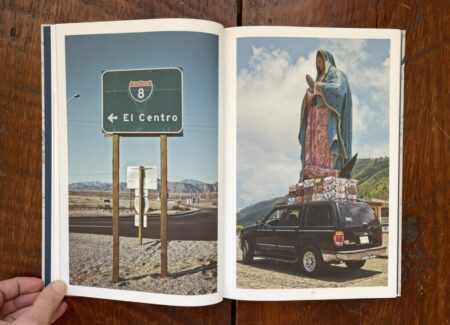

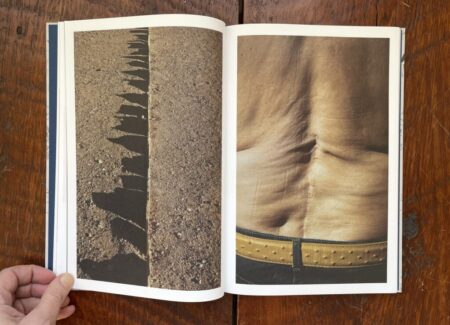

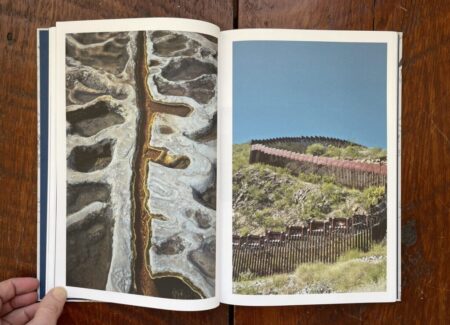

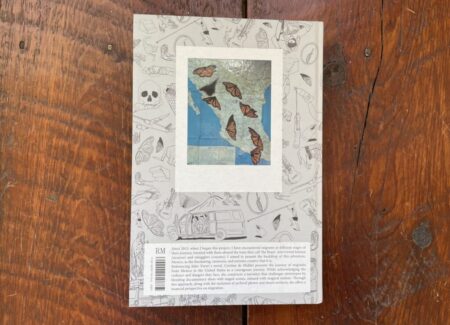

De Middel has a sophisticated and inspired sense of sequencing, and her pairings often key on color themes, formal echoes, or a kind of call-and-response connection between the two pictures. A dark hole in a cave is paired with a view through the hole in a put-your-face-through cutout, looking in and looking out; a man points upward as if telling us to ascend, next to a set of stairs to nowhere; a blindfolded young man rides on the train while monarch butterflies migrate across a map of Mexico, both on their way; a jagged line of sharp deterrents in the sand matches the scars on a man’s back; a red rope jumps between cacti in the desert near a man with a red cloth over his face like the cape of a superhero; a masked man poses with his hand clutched like a claw, near an aging dry cactus curved in a similar manner; a spray painted arrow on a cactus (offering direction in the desert) points to a man wearing a cactus crown and a green cape; the illusions of camouflage clothing are matched by those of a picture window out to the desert; the illuminated formations in a cave are echoed by the shadowy masked pose of a drug cartel enforcer; and the geometric shadow in an archival picture fits perfectly with the shape of a stretch of border wall. These relationships and refrains continue throughout the book, with an impressive degree of cleverness and ingenuity, making each page turn a kind of treasure hunt for image parallels and thematic through lines.

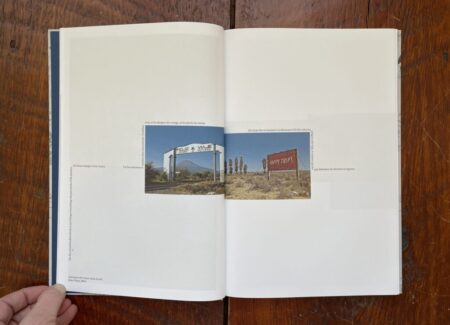

But Journey to the Center isn’t only made up of these kinds of pairings. De Middel builds other two picture sets, using the gutter to connect the two photographs and allowing quotes from Jules Verne to geometrically wander around the white space in three languages, making connections between the text and images. And when she wants to extend the sequencing to four, five, or even six pictures, de Middel adds foldouts that turn the images into a kind of musical score or a melody, linking the pictures into more elongated series, with the unfolding process breaking up the regular refrain of the two image spreads. Along the way, she also adds longer first person interviews with several migrants, their harrowing stories putting a more specific face on the more anonymous migration story we are used to seeing, a few having dangerously traversed a handful of countries before even getting to Mexico. And of course the photobook ends with imagery made at the Center of the World, with glossy full bleed pages placing it in the context of other fantastic desert attractions like an ice cream castle and a dinosaur.

In the end, when seen as one entire artistic statement, Journey to the Center offers a symbolic re-imagining of the complex migration conversation we are all having at the moment. In a sense, its message is not as grim or dispiriting as an in-depth documentary following of this long journey through Mexico could easily have been; instead, it opts for something more layered and impressionistic, an aggregation of resonant visuals that can be interpreted with the freedom to match the very real fear and exhaustion with more optimistic splashes of hope and power. The cover of the photobook is wrapped with line drawings of these various images and symbols, as if to say that this story includes all of these things, even the most eccentric and unlikely of de Middel’s disparate inclusions.

Journey to the Center features many standout single photographs that will undoubtedly make the rounds on the Internet and in art fairs, but hopefully, these touchstones will lead people back to de Middel’s more integrated photobook narrative, which places the burning guitar, the donkey painted like a zebra, the stuffed mountain lion, and the various almost superheroes in a richer and more nuanced context. Its ancient story begins on the way to libertad (“freedom”) and ends in hazy Los Angeles, with countless episodes of daring and heroism judged on little more than randomness or the flip of a coin. As grave, extreme, and overwhelming as this whole migration topic is, de Middel isn’t afraid to infuse it with a bit of swagger and absurdity, giving this “happy trip” (as seen in a pair of signs in Spanish/English) an unlikely new frame.

Collector’s POV: Cristina de Middel is represented by Magnum Photos (here). Her work has little secondary market history at this point, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.