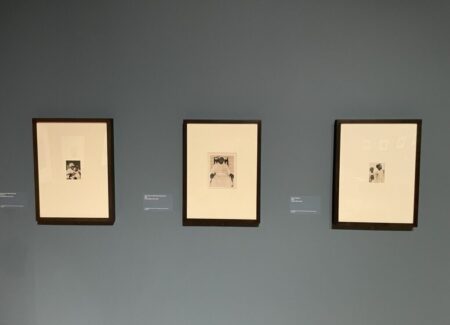

JTF (just the facts): A retrospective exhibition, installed in a series of rooms on the 4th floor of the museum. In general, the works are presented matted in black frames, hung against blue and brown walls and partitions. (Installation shots below.)

The exhibit was organized by Drew Sawyer formerly of the Brooklyn Museum in New York (with assistance from Imani Williford), in collaboration with Fundación MAPFRE (February 15-May 12, 2024) and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (September 28, 2024-February 9, 2025).

The following works are included in the exhibition:

A Collaborative Spirit (entry area)

- 3 gelatin silver prints, 1927/1992, c1940, c1952

- 3 pigmented inkjet prints, c1928/2023, c1945/2023, 1955/2023

- (vitrine): 1 Rolleiflex camera, c1950; film rolls; Alma Lavenson: 3 pigmented inkjet prints, c1930/2025, 1952/2025; Saul Leiter: 1 gelatin silver print, c1950; Eiko Yamazawa: 1 pigmented inkjet print, 1955/2025

Photojournalism and the City

- 19 gelatin silver prints, c1920/1992, 1922, 1922-1924, 1928, c1936, c1937

- 3 toned gelatin silver prints, c1920, 1935, c1937

Portraiture

- 20 gelatin silver prints, 1920, c1920, c1925, 1928, c1928, c1940, c1945, 1964

- 3 toned gelatin silver prints, c1935, c1940

- 2 toned gelatin silver prints with graphite, c1925, 1936

- 1 pigmented inkjet print, nd/2023

Travels Abroad

- 12 gelatin silver prints, 1927, 1927/1992, 1928/1992

- 1 pigmented inkjet print, 1928/2023

Photography and the American Scene

- 23 gelatin silver prints, 1927-1928, 1930, c1930, c1935, 1937, c1940, 1942, 1948, c1955

- 4 toned gelatin silver prints, c1920, c1930, 1944, c1955

- 1 pigmented inkjet print, 1925/2023

- 1 bromide print, 1930

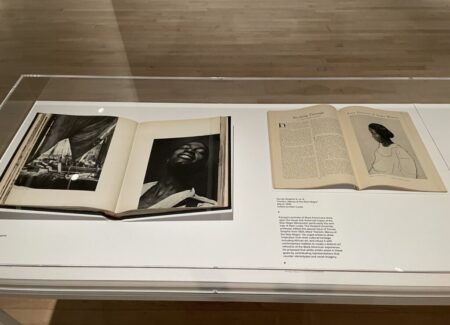

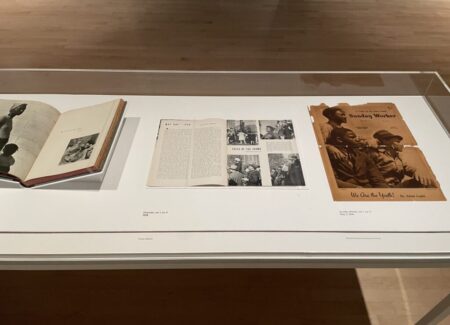

- (vitrine): 1 book, 1933-1934; 1 magazine, 1925; 1 magazine, 1964; 1 book, 1933; 1 book, 1929

The New Negro Movement: Art Representations of Blackness

- 9 gelatin silver prints, 1930, 1931, 1932, 1933, c1937, 1950

- 5 toned gelatin silver prints, 1932, c1932, 1933, c1938

- 1 pigmented inkjet print, 1936/2023

Portraits of Artists

- 10 gelatin silver prints, 1934, 1934/1992, 1936, c1940, 1950, c1950, c1964

- 5 toned gelatin silver prints, 1938, c1950, c1955

- 1 bromide print, 1940

Nature Studies

- 4 gelatin silver prints, c1935, 1948, c1950

- 3 toned gelatin silver prints, 1948

Travels to the U.S. South

- 16 gelatin silver prints, 1948, c1948, 1948-1950, 1950, 1964

- 7 toned gelatin silver prints, 1948, 1948-1950

- 5 pigmented inkjet prints, 1948-1950/2023, 1963/2023

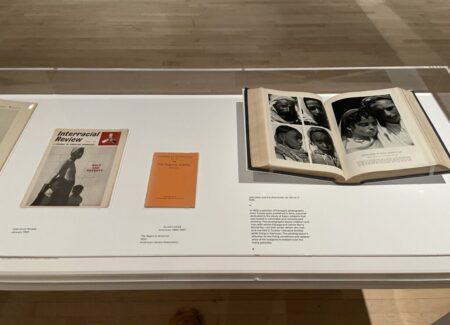

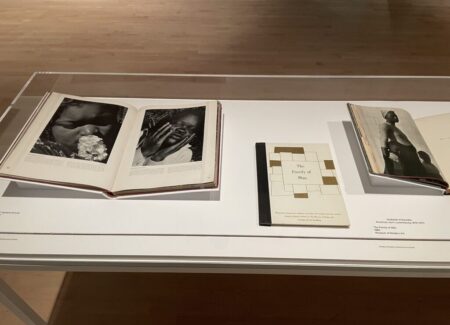

- (vitrine): 1 book, 1941; 1 book, 1955; 1 magazine, 1938; 1 newspaper, 1936

The Worker-Photography Movement

- 2 pigmented inkjet prints, 1937/2023

- 1 toned gelatin silver print, 1935

- 7 gelatin silver prints, 1935, 1936, 1948-1950, 1950

- Leo Hurwitz: 1 16mm film, black-and-white, sound, 7 minutes 13 seconds, 1934

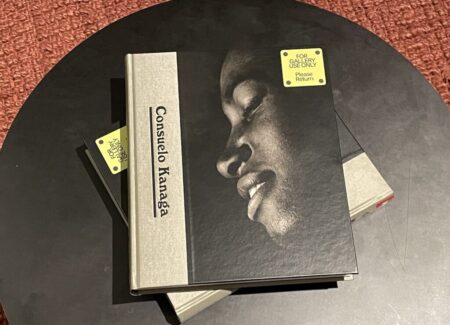

A catalog of the exhibit has been copublished by the Brooklyn Museum, Fundación MAPFRE, and Thames & Hudson (here). Hardcover, 9.8 x 11.5 inches, 280 pages, with 150 reproductions. Includes essays by Drew Sawyer, Shalon Parker, Ellen Macfarlane, and Shana Lopes(Cover shot below.)

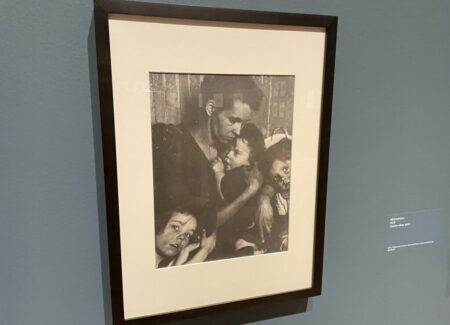

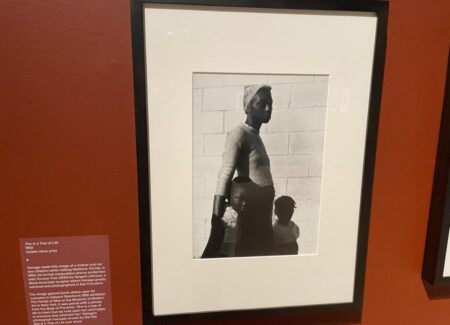

Comments/Context: For those that can identify the name of Consuelo Kanaga and place it in the larger history of 20th century photography, her now-iconic photograph “She is a Tree of Life to Them” is likely the source of that recognition. Made in 1950, in Florida, while on a trip through the South, it’s a portrait of a mother and her two children. The mother figure stands against a white brick wall, wearing a white headscarf and a tight fitting white shirt, with her two young children standing by her side in the shadow of her body, her arms creating a protective triangle, as if she was gently (or warily) gathering them near. Made in a crisp Modernist style, with attention to the subtle contrasts of light and dark, it’s a photograph filled with empathy, dignity, and understated grace, a paragon of motherhood drawn out of the rhythms of the everyday.

Perhaps it is a reflection of how race permeates our cultural perception and vision, but the combination of the fact that the family in this famous image is black and Kanaga’s relative obscurity has often led to implied questions about the artist’s race – given the respectful beauty and attentiveness consistently seen in Kanaga’s images of black people, maybe she was black as well. But indeed, Consuelo Kanaga was white, which tends to confuse our simplistic assumptions and prejudices about who can see whom. And without looking at more of Kanaga’s work, many have been left wondering just who this woman was, and why was she able to photograph black subjects so clearly and exquisitely, especially in the decades before the Civil Rights movement gained momentum.

This six-decade retrospective exhibition, the first on Kanaga in more than thirty years and drawn from the Brooklyn Museum’s extensive holdings of Kanaga’s work, amply provides the context necessary to understand where “She is a Tree of Life to Them” came from. And indeed, this image is included in the show, installed near the end of the exhibit (actually without much fanfare), which makes it much clearer how this one photograph fits into the larger arc and progression of Kanaga’s long artistic career. Organized both chronologically and aesthetically, largely in groupings by subject matter, the understated curatorial structure provides us all the supporting evidence we need for how and why Kanaga came to make the singular photographs that she did.

Born in Oregon in 1894, Kanaga was one of the first women to become a staff photojournalist at a major newspaper (The San Francisco Chronicle) in 1915, and in subsequent years, she would work for newspapers in Denver and New York, as well as for several national magazines. And it’s in her early photojournalism that we see the seeds of a passion for social justice that would continue throughout her life. Of course, there are images from this period of city architecture and bridges, but also of the anguished faces of poverty and malnutrition, the daily routines of workers, the lines of laundry hanging from tenements, and the men sleeping on the trash strewn sidewalks of the Bowery, her genuine interest in these issues of injustice and inequality infusing her photographs with tactile sensitivity.

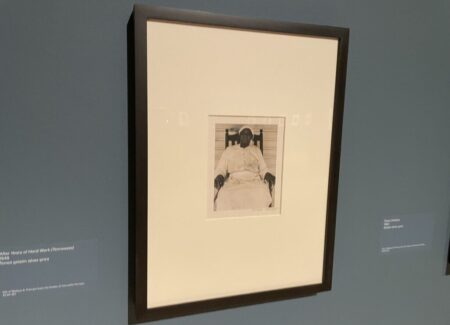

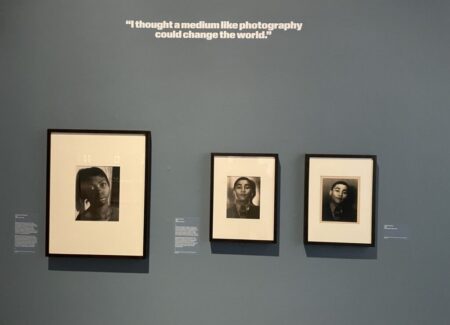

While she was in San Francisco (in the early 1920s), Kanaga also opened her own portrait studio, catering to city’s wealthy patrons, and it is in some of these pictures that we find Kanaga experimenting with more Modernist and avant-garde aesthetics, from close cropping and deep shadow to faces seen in profile and accompanied by the gestural posing of hands. It was about this same time that she joined the California Camera Association of San Francisco, which led her to make connections with some of the other female photographers working in the area with similar interests, including Imogen Cunningham and Dorothea Lange. Then in the late 1920s, Kanaga traveled abroad, making images in Europe and North Africa, where she applied her growing photographic talents to a range of new subject matter.

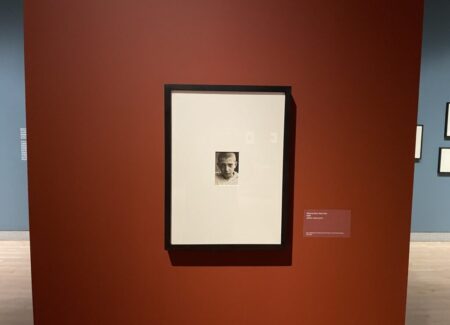

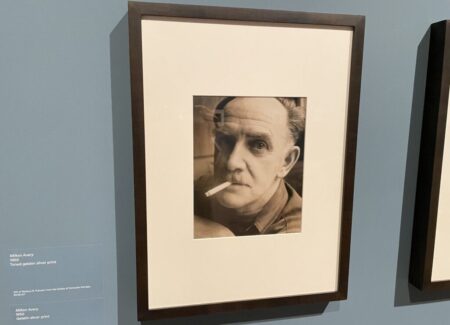

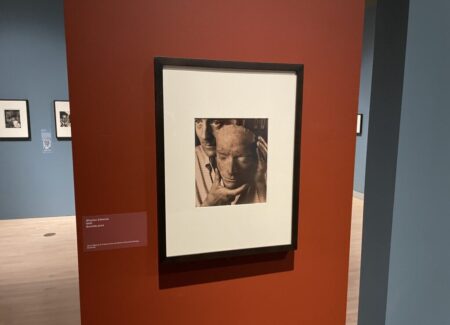

In the next decade (the 1930s), Kanaga pushed her all disparate photographic interests (photojournalism, Modernism, portraiture, and social justice, among others) forward essentially simultaneously. The show features a robust selection of her Modernist compositions, where natural still lifes of wagon wheels, kitchens, water pitchers, glassware, flowers, and even a horse’s eye, as well as dark silhouetted architectural views of rooftop vents, window frames, telephone poles, and skyscrapers were seen with rich tonal precision and clarity. Another section of the exhibit brings together Kanaga’s portraits of writers, musicians, and artists from this same period, including memorable images of Langston Hughes, Morris Kantor, Alfred Stieglitz, and Milton and March Avery (from a decade later); there’s also a fine portrait of the sculptor Wharton Esherick (from 1940) holding a mask of his own face, making clear that Kanaga was continuing to experiment with the more surreal possibilities of portraiture.

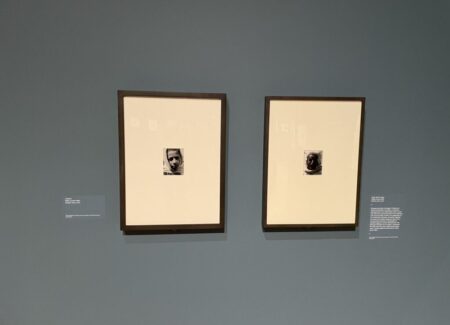

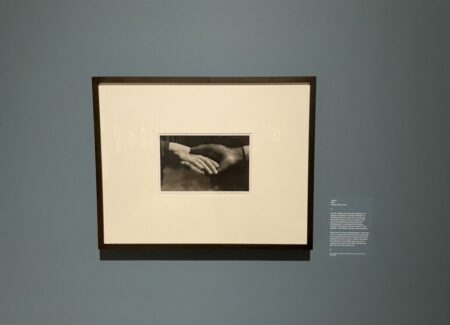

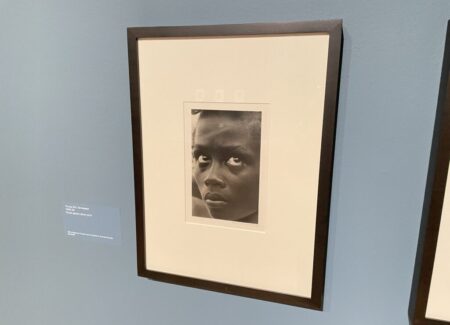

The 1930s were also the heyday of the Harlem Renaissance, and in particular the New Negro Movement which sought to celebrate black self-expression and identity. Kanaga made a number of portraits of black Americans during this time, leveraging both the spirit of the moment and her now considerable aesthetic and technical skills. An image of clasped hands, one black and one white held in solidarity, provides an introduction of sorts to this section of the show, followed by a confidently ecstatic portrait of the singer and actor Kenneth Spencer (from 1933). Additional images get up close to the faces of black children, who engage the camera with attentive openness, and capture other adults young and old, who pose with calm awareness or look outside the frame with upward looking optimism and hope. One small group of pictures eloquently captures Kanaga’s driver and handyman Eluard McDaniel, who brings his hands toward his face in a variety of quietly comfortable arrangements. And one image made for the Sunday Worker magazine (in 1936) takes a more overtly leftist political stance, bringing together three workers – one black, one white, and one Asian – celebrating a multi-ethnic working-class American reality.

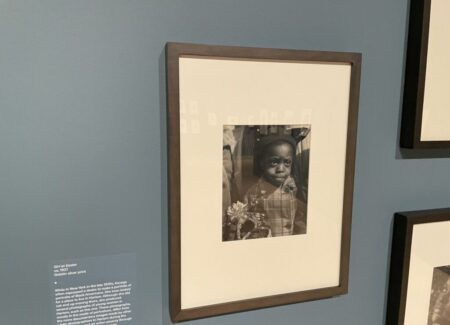

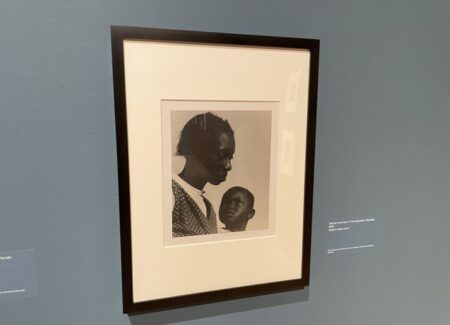

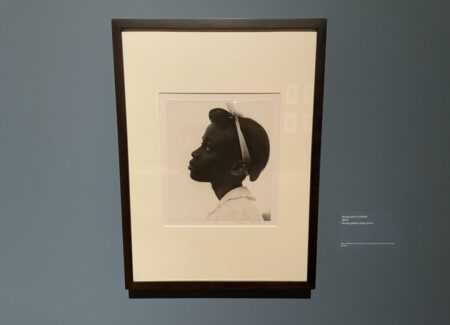

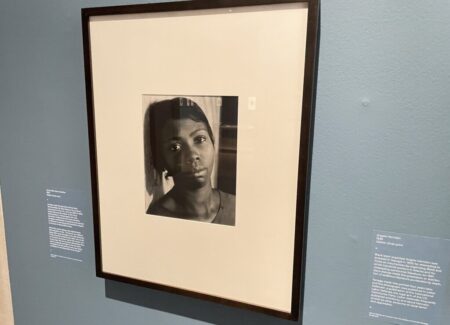

After a short detour to some nearly abstract nature studies Kanaga crafted in the late 1940s, all of her interests seem to converge in a series of images made on trips to the South throughout the next decade. Her primary subject was the lives of local black farm workers and laborers, particularly those working the reclaimed swamplands. And while a few of the images on view here offer the context of a front porch, a wooden fence, some moss covered trees, some low hills in the background, or even a cow getting milked, for the most part, Kanaga narrows her frames down to closely cropped faces. And it is here that this exhibition comes into its power zone, delivering a flurry of knockout images one after another, of single faces, of mothers with young children, and particularly of young black girls. Kanaga generally uses the bright sunlight of midday to amplify the contrasts of light and dark, in some cases, creating figures that function almost like silhouettes. But up close, Kanaga shows us individuals and emotions, where weariness, joy, and concern alternately wash across faces.

It’s clear that in particular Kanaga spent time building trust with the young girls, often making multiple exposures and image variants. This leads to clusters of photographs with heads turned one way and then another, some cropped down and others stepped back to show a bit more of a shirt or white dress. The consistent tenderness and empathy in these pictures is what stands out; Kanaga’s pared down Modernist aesthetics tighten our attention, but it is the glance over some apple blossoms, a gentle profile with a hair ribbon, or an arms crossed schoolgirl pose with a sun hat that feel altogether timeless. This parade ultimately leads to “She is a Tree of Life” (and a variant from another angle), which now seems like one of many in a pattern of attentiveness instead of a single resonant outlier.

The last room in the exhibit continues Kanaga’s exploration of workers, with a few more superlative portraits (including a tall elongated image of a black man in overalls) mixed together with images of black workers in the fields, harvesting crops, carrying bushel baskets, and rallying in the streets. Kanaga’s portrait of Annie Mae Merriweather (jumping back to 1935) is particularly poignant, the traumas she had endured (including the lynching of her husband) seeming to pour out of her eyes.

What’s clear from this handsome retrospective exhibition is that Kanaga first and foremost had a powerful and enduring commitment to the plight of others. She then leveraged that energy and liberally used various modes of photography as a form of personal visual advocacy, whereby her images told the stories of those she felt were overlooked, marginalized, or otherwise at risk in American society. This show smartly defines Kanaga’s rightful place not only in the 20th century American documentary tradition, but also in the broader aesthetics of American Modernism. Her crossover blends the two in unique ways, creating a body of work that feels deeply and authentically rooted in justice and integrity, but that is similarly informed by new ways of seeing. As seen here, Kanaga will ultimately be measured by the strength of her many indelible portraits, whose striking dignity and grace still have the power to astonish.

Collector’s POV: The estate of Consuelo Kanaga does not appear to have consistent gallery representation at this time. Kanaga’s work has been intermittently available in secondary markets in the past decade, with prices ranging from roughly $2000 to $107000.