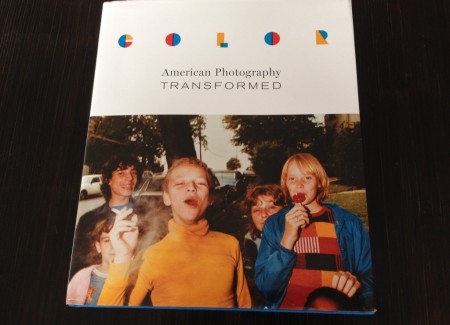

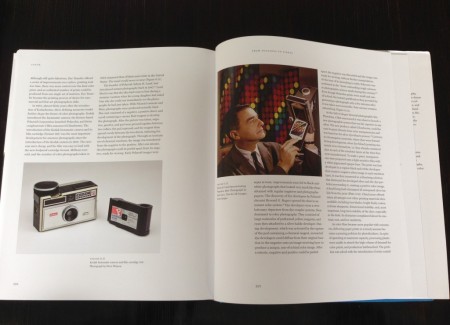

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2013 by the University of Texas Press (here) to coincide with an exhibition organized by the Amon Carter Museum of American Art (October 5, 2013-January 5, 2014). Hardcover (10×12 inches), 344 pages, with 78 full-page color plates and 97 figures, priced at $75. Text by John Rohrbach with an essay by Sylvie Pénichon. (Spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: It is shocking how little serious writing about photography over the last 40 years has addressed the innovation of color. Instead of untangling its loopy, boom-and-bust past or analyzing differences between polychromatic vision and one that relies on shades of gray, critics and journalists have tended to dwell on William Eggleston’s 1976 show at MoMA—the flashpoint when color photography achieved respectability (even if Eggleston and curator John Szarkowski at the time did not.)

Essays and articles, if they’re ambitious in their backward glance, will also cite Paul Outerbridge’s carbro prints in the 1930s, Ernst Haas’s impressionistic work for Life in the 1950s, and Helen Levitt’s color slides in the 1970s. There may be references to Autochromes, Kodachrome, Coloramas, and Polaroid. Invariably, somewhere in the piece, mention will be made of Walker Evans’s withering verdict uttered in 1969 that “color photography is vulgar.” (I write here in a mood of contrition, as a serial purveyor of such superficialities myself.)

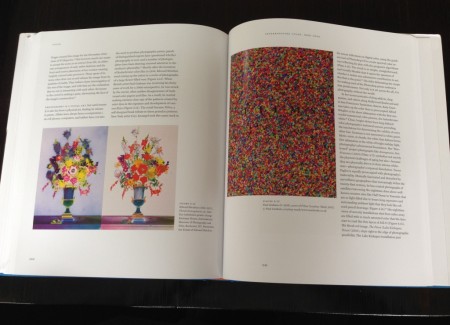

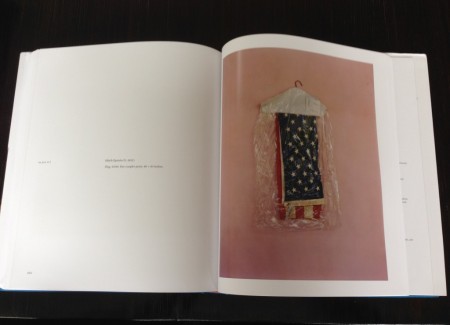

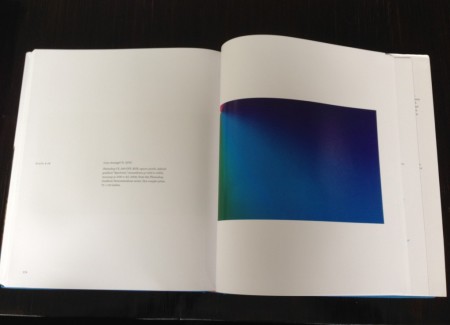

John Rohrbach’s terrific book, copiously illustrated and footnoted, significantly enlarges the scope of this history and our understanding. The four chapters—“Inventing Color Photography”; “Defining Color, 1936-1970”; “Using Color, 1970-1990”; and “Interrogating Color, 1990-2010”—offer a sweeping view of multi-hued photography as a problem that bedeviled—and a mirage that beguiled—generations of inventors, artists, critics, and businesses.

The historical focus is squarely on developments in the U.S., beginning in the 1850s with the Rev. Levi L. Hill from upstate New York, a Baptist minister who boasted that he had devised a method for making color Daguerreotypes. Dismissed as a fraud for much of the 20th century, he has in recent decades been partially vindicated by researchers at the Smithsonian and the Getty who believe his “Hillotypes” were both hand-dyed and capable of crudely reproducing reds and blues.

Excitement and let-downs became so frequent in the 19th century that cynicism became the standard response to claims like Levi’s. “’Color photography’ has been ‘discovered’ at more or less regular intervals ever since photography was invented,” a 1907 journal wearily noted, “until latterly it has been used by the Sunday papers to alternate with the sea serpent as a space filler in the dull season.”

Even after a proven method was found, artists usually found good reasons to prefer black-and-white. Stieglitz was one of many to have a bi-polar reaction to Autochromes. “The possibilities of the process seem to be unlimited,” he enthused in 1907. He was certain a method would soon exist for making prints on paper. But a year later he had turned his back on this invention of the Lumière brothers. The lack of control over color intensity and other issues led him to respond in monochrome to the challenge of the radical painting coming out of Paris.

Rohrbach’s account unearths forgotten controversies and identifies a pantheon of unexpected heroes. He gives proper credit to chemical engineers, such as Leopold Godowsky and Leopold Mannes (God and Man, as their Kodak colleagues called them) who invented Kodachrome in the 1930s. It was Nancy Newhall, not her husband, who in a 1941 article for U.S Camera “Painter or Color Photographer?” succinctly stated what was needed if artists were to adopt the new technology: “not photographs with color but color photographs.”

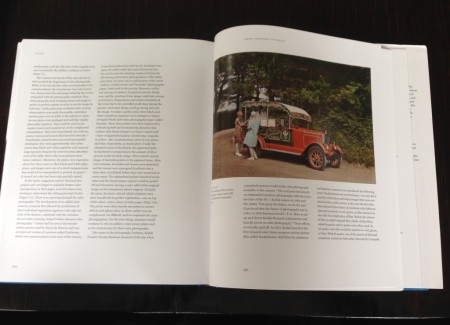

Ansel Adams is one of the main characters in the middle chapters. His tortured feelings about the possibilities outlined by Newhall went from jubilation in 1946 after he had developed a several Ektachromes of Zion National Park (“the G-DambnestSOBchen wonderful thing I ever did”) to renunciation of the process in a 1950 issue of the Photo League journal (hues in color prints “never seem to have the vitality and validity that they have in nature”) to accommodation with the new medium for commercial purposes (Kodak paid him handsomely for his Coloramas in Grand Central Terminal) and finally to a tentative embrace of Polaroid in the 1960s. (The co-inventor of the Zone System never fully converted, though, and is credited here as the source for the famous put-down beloved by the black-and-white faithful: “If you can’t make it good, make it red.”)

Rohrbach is diplomatic about Adams’s peculiar behavior with his friend Eliot Porter, one of the few photographers with the patience and skill to master Eastman Wash-Off Relief Printing. In 1962 Adams hosted a party for the Sierra Club publication of Porter’s In Wildness is Preservation of the World. But he objected so viscerally to the work that he left the room rather than be forced to comment on the pictures. As Porter had noticed in 1958: “photographers on the whole do not like to look at color prints, whereas painters are usually very much interested.” Fairfield Porter, Eliot’s brother, was one of those paying respectful attention to the challenge color photography represented for realist painting: “Can we as adults be sure that we see more deeply, through art, than the photographer who pretends to do nothing but pays the closest possible attention to everything?”

By the 1960s the inevitable triumph of color was apparent to many, even as resistance intensified in some quarters. Younger photojournalists Larry Burrows and Tim Page photographed the Vietnam War in color, an approach denounced by David Douglas Duncan. “To this day I’ve never made a combat picture in color—ever,” he said in 1968. “And I never will. It violates too many of the human decencies and the great privacy of the battlefield.” (It’s interesting that a few outstanding conflict photographers from the post-Vietnam era, such as James Nachtwey and Gilles Peress, have apparently sided with Duncan, whose staunch opinions were forged during the Korean War.)

Toward the end of their careers Edward Weston and Harry Callahan developed warm feelings for color, and many years after Stieglitz had lost hope in color his protegé Edward Steichen was still a believer. That is, until 1955, when organizing “The Family of Man,” a show of 500 prints for MoMA, he chose an image of an atomic blast explosion as the last and only photograph in color.

Rohrbach is ecumenical enough that he finds rooms to credit the influence of commercial publishers, such as Condé Nast, for financing expensive color photography in its pages and for promoting color as an expressive tool for fashion and advertizing. Its 1935 book Color Sells includes a caveat that was perhaps truer then than now: “color is like dynamite—dangerous, unless you know how to use it. The high attention-value of color lays a mediocre color page open to keener criticism than a poor black-and-white reproduction. If the final result is harsh, garish, or flat, it repels—and repels sharply.”

The third chapter, the center of which details reactions by critics to the Eggleston show, does not ignore what Stephen Shore and Joel Meyerowitz were doing even earlier, nor to Garry Winogrand’s timid forays into color. (Rohrbach’s contention that Szarkowski “did not fully understand” Eggleston’s photographs may be true; but it probably just as accurate to say that Eggleston did not understand them himself.)

It is good to see text and full-page reproductions devoted to Mark Cohen (whose “Boy in Yellow Shirt Smoking” is the cover), Neil Winokur, Anthony Hernandez, Cory Arcangel, and Marco Breuer, along with more familiar names, such as John Divola, Gregory Crewdson, John Pfahl, Alex Webb, Jan Groover, Mitch Epstein, Tina Barney, and Richard Misrach.

The Americans-only nature of this particular history has its limitations. The absence of European photographers is felt acutely in the last chapter, covering the post-1990s art scene. Experimental color processes, which are again dominant in galleries in this decade after a long period when naturalist documentary held sway, can itself be traced back to the inspirational books and teachings of a European: Moholy-Nagy, first at the Bauhaus and then at the Institute of Design in Chicago. The Hungarian proselytizer, and students such as Arthur Siegel, get their due here, but the nationalist borders around the book prevent Rohrbach from exploring photography as a global phenomenon in the age of digital communications and international art fairs.

Much of this history has been written about before, in books by Brian Coe, Van Deren Coke, Naomi Rosenblum, Keith Davis, Pamela Roberts, as well as in more specialized studies, such as Photography and Art: Interactions since 1946 (1987) by Andy Grundberg and Kathleen McCarthy Gauss; and Starburst: Color Photography in America 1970-1980 (2010) by Kevin Moore.

But none of these volumes have the coherence or readability of Rohrbach’s tale. What’s more, Sylvie Pénichon’s essay on the technical history of color photography, and its unique conservation issues, have seldom been highlighted, or even touched upon, in many of these earlier tomes.

Arguments can always be raised about an author’s judgments on the work of favorite artists, including why some are absent from these pages. That shouldn’t detract from what Rohrbach’s scholarship has done: help us to think more deeply about how color does (and doesn’t) alter the meaning of images. It’s a book that should be in the library of anyone who collects or cares about photography.

Collector’s POV: Given the survey nature of this exhibition catalog and the many photographers included, a detailed study of relevant secondary market and gallery prices is beyond the scope of what can easily be addressed here.

Sally Eauclaire’s 1981 book The New Color Photography is another nice reference point in this discussion: http://amzn.to/NdVsDs