JTF (just the facts): A wide ranging group show presentation drawn from the museum’s permanent collection, displayed in loose chronological order across a series of 16 connected rooms on the 2nd floor.

For each room, the photographs and films on view are listed below:

201 Public Images

- Dara Birnbaum: 1 video, 1978-79, 5 minutes 50 seconds

- Louise Lawler: 1 silver dye bleach print with text, 1988

- Cindy Sherman: 24 gelatin silver prints, 1977, 1978, 1979, 1980

202 Downtown New York

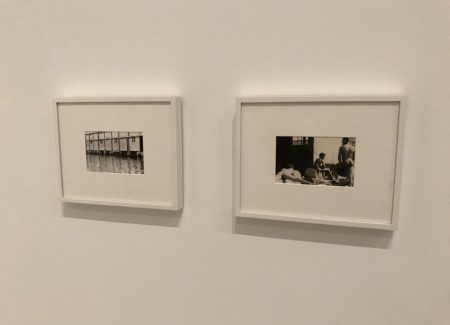

- Alvin Baltrop: 2 gelatin silver prints, 1975-1986

203 Hardware/Software

- Jimmy DeSana: 2 silver dye bleach prints, 1982, 1984

- Barbara Kruger: 9 offset lithographs and screenprints with lithographs, 1985

- Laurie Simmons: 1 silver dye bleach print, 1989

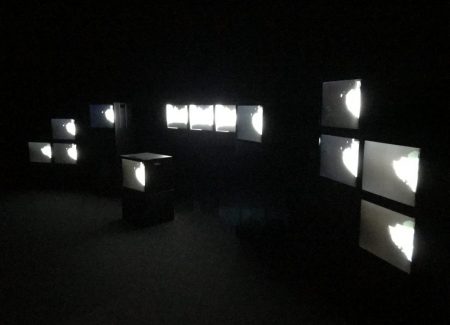

204 Gretchen Bender’s Dumping Core

- 1 four channel video, 1985, 13 minutes

205 Print, Fold, Send

- In cases: photo-based works by Alfredo Jaar, Paulo Bruscky, Maris Bustamente, Anna Bella Geiger, Hudlinson Jr., Claudio Perna, and others, late 1970s-early 1980s

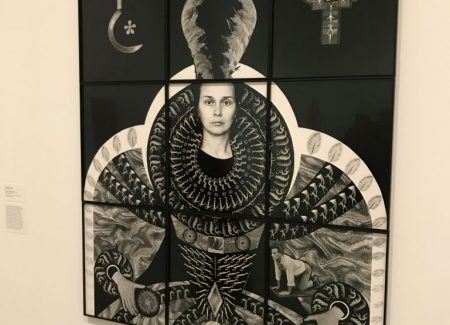

206 Transfigurations

- Zofia Kulik: 1 set of 9 gelatin silver prints, 1997

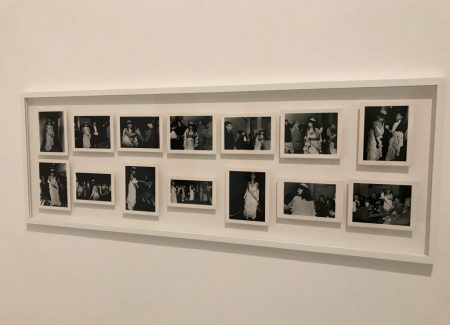

- Lorraine O’Grady: 1 set of 14 gelatin silver prints, 1980-1983/2009

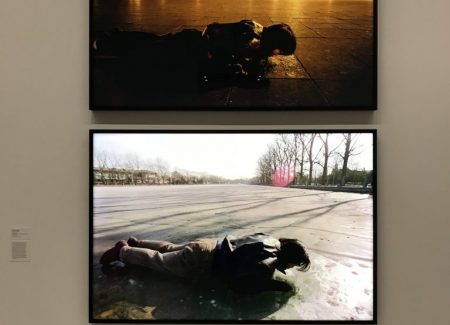

207 Before and After Tiananmen

- Cang Xin: 8 chromogenic color prints, 1999

- Song Dong: 1 diptych of color transparencies on lightboxes, 1996/2018

- Xiao Lu: 1 chromogenic color print, 1989/2006

- Zhang Pelli: 1 video, 1991, 36 minutes 49 seconds

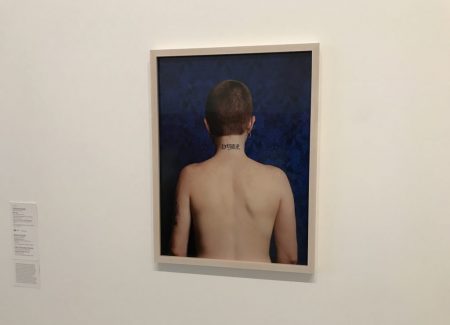

208 True Stories

- Rineke Dijkstra: 11 chromogenic color prints, 1994-2008

- Isa Genzken: 1 slot machine, paper, chromogenic color prints, and tape, 1999

- Lyle Ashton Harris: 1 set of 9 chromogenic color prints, 1996

- Catherine Opie: 1 chromogenic color print, 1993

- Wolfgang Tillmans: 23 chromogenic color prints (in various sizes), 1986, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1995, 1997, 1998

- Christopher Williams: 1 dye transfer print, 1992

209 Inner and Outer Space (no photography)

210 Richard Serra’s Equal (no photography)

211 JODI’s My%Desktop (no photography)

212 Sheela Gowda’s Of All People (no photography)

213 Wu Tsang’s We hold where study (no photography)

214 Surface Tension

- Yto Barrada: 1 set of 4 chromogenic color prints, 2004

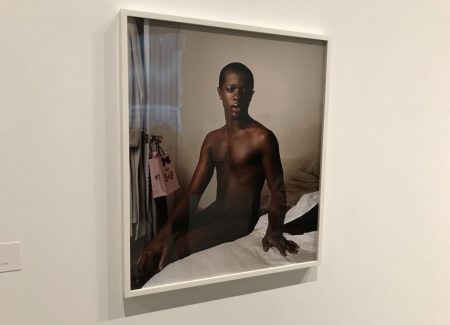

215 Worlds to Come

- Trisha Donnelly: 1 video, 2014, 35 seconds

- Deana Lawson: 1 pigmented inkjet print, 2009

216 Building Citizens

- Gordon Kipling: 1 digital print on acrylic panel, 1995

- Gordon Matta-Clark: 1 silver dye bleach print, 1978

- Alvaro Siza: 8 gelatin silver prints, 1974-1977, 1 diazotype print, 1974-1977

- Amanda Williams: 7 pigmented inkjet prints, 2014-2016

(Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: The third and final section of MoMA’s reinstalled permanent collection galleries, as seen in a series of rooms on the museum’s second floor, picks up the historical thread in the late 1970s and tries to pull it all the way to the present. And while the earlier chunks of history (1880s to 1940s on the 5th floor, reviewed here, and 1940s to 1970s on the 4th floor, reviewed here) successfully used chronology and thematic structure to organize the argument and its flow, that same impulse largely breaks down in these galleries of more recent work, particularly if we are looking for a coherent statement about the history of the photography in the past several decades. While a faint heartbeat of chronology can indeed be followed, what is absent is a set of defining visual milestones that mark the photographic turning points in the contemporary period.

The second floor gets off to a promising start with a small gallery featuring the works of the Pictures Generation. Cindy Sherman’s film stills take center stage, filling an entire wall, which would normally be fine, given their durable importance, except that they unbalance the rest of the media appropriation story that was ultimately so influential. Louise Lawler and Dara Birnbaum are shoehorned in, but the installation feels one-sided; a few less Shermans and an early Richard Prince or two might have made a more forceful argument.

The story then moves to downtown New York in the early 1980s, anchored by Basqiat and Haring, with a pair of Alvin Baltrop photographs of the West side piers included to fill out the mood of the moment. In the next room, Jimmy DeSana, Laurie Simmons, and Barbara Kruger extend the identity investigations further, and nearby, a pulsating Gretchen Bender installation on more than a dozen TV monitors delivers a sensory overload of computer graphics, spinning logos, breaking glass, and shooting noises. Featuring the Bender piece so prominently is an inspired choice, and one that reaffirms her place as an underappreciated pioneer of media art. Then, as if to walk back from that technology-centrism, the next room turns to mail art (largely from Latin America), with its analog hand crafting, rough printing, and guerrilla distribution tactics.

It is at this point (in the mid 1980s) that the arc of art history starts to go missing in this series of rooms, the lines of thinking and the thematic connections becoming so diffuse that they fail to generate conclusions – the march of enduring importance wanders and bends back on itself, with more obscure and tangential inclusions muddying the water. A room called “Transfigurations” gathers together works depicting the female figure, and while the inclusions of Mendieta, Dumas, Noland and others make sense, the gathering feels ungrounded without the context of 1960s and 1970s feminist art (particularly photography). The same can be said for a room filled with art (mostly photography) from China in the 1980s and 1990s, in the aftermath of the Tiananmen uprising; it’s not that the subject isn’t instructive or that the choices aren’t valid – it’s that without Ai Weiwei, Zhang Huan, RongRong, and others to provide some ballast, these secondary works feel untethered and fail to communicate the complexity of what was taking place artistically.

“True Stories” is the title of the next room, which, once the Talking Heads reference passes through your mind, turns out to be a 1990s era survey of alternative approaches to portraiture, largely in photography. Aside from the annoying inclusion of Christopher Williams where he doesn’t really belong, the photo choices here are spot on – Rineke Dijkstra and her time-lapsed portrait of Almerisa (from child to young woman to mother), Lyle Ashton Harris and his blood-red mood board of collaged influences and memories, Wolfgang Tillmans and his installation of multi-sized portraits, still lifes, and in-between moments from his early career, and Catherine Opie’s powerful DYKE tattoo portrait (why she only got one image when the others got entire walls is a mystery). All of these selections (except Williams) fit the criteria of being critical projects or bodies of work (of the period) made by durably influential photographers. And yet, what kept running through my mind while seeing these choices was, would my assessment be any different if the walls had been filled by 1990s era works by Sally Mann, Nan Goldin, Carrie Mae Weems, or Philip-Lorca diCorcia (as an example)? This particular moment in photography history seems to have encouraged experimentation with portraiture, and a deeper backstory to why that occurred would have been instructive.

As I wrestled with this question and moved on to the next rooms, I suddenly stopped in my tracks and had a “wait a minute” moment. I’d somehow reached the late 1990s in art history without addressing a critical sea change in photography that took place at that time – the introduction of monumental scale, thereby placing large photographs on the same physical footing as large paintings. Where were Andreas Gursky, Thomas Struth, Thomas Ruff, and the rest of the cohort from Düsseldorf, as well as tableaux staging of Jeff Wall and the appropriated cowboys of Richard Prince? This whole transformation of the medium (and the landmark pictures made by these masters) is missing.

Puzzled by this seemingly obvious omission, I stumbled through the next few rooms, many of which are single room installations of large works, videos, or other solo presentations (none of which is photography), only to come upon the last three rooms, which feel like grab bags of recent works, and a random bolt-on of architecture. One called “Surface Tension” purports to be about collage, flux, and digital change, but the only photographs in the room are Yto Barrada’s long distance bus logos, that, while digitally cleaned up, hardly seem representative of everything that has happened in photography since the digital revolution. “Worlds to Come” is the essentially final room, where photography is represented solely by a contemporary Deana Lawson portrait, a strong and memorable one to be sure, but it’s unfair to ask that one picture to carry so much load.

Seeing this compendium of recent contemporary rooms, one might reasonably wonder about why the museum opted to leave out basically the entire sweep of photography made since the mid 1990s. While it is always hard to definitively declare winners so quickly, the chance to educate visitors about the exciting revolution in photography that has been going on in the past few decades was missed. There is almost no photographic appropriation on view, no construction, no staging, no archive mining, no native digital work, no digital mark making, almost no manipulation, and no appreciation of networked or machine imagery, the Internet, or even the impact of the smartphone camera and the selfie. Nor have any of the pioneers of digital photography been recognized for their important artistic contributions. As a result, these rooms on the second floor end with a whimper, at least from a photographic perspective. What could have been a forward looking, inspiring, and optimistic sampler of current photographic risk-taking ends up feeling dull, retrograde, and largely out of touch, which isn’t a true reflection of the strength and expertise of MoMA’s photography department.

So as I ended my travels through the three floors of art history, these rooms on the 2nd floor gave me pause. As I got closer and closer to the present, the clarity of vision that informed the upper floors was systematically lost. These last handful of rooms in this permanent collection installation can’t possibly represent what MoMA thinks is most (or even meaningfully) important in contemporary photography – in fact, there is hardly any photographic point of view being offered at all, which is troubling. As they reboot these rooms later this spring, let’s hope the photo curators fight hard to include a compelling vision not only of the distant past, but of more current innovations.

Collector’s POV: Since this is a museum show of permanent collection highlights, there are of course no posted prices. Given the broad number of artists and photographers included in the exhibition, we will forego our usual discussion of individual gallery representation relationships and secondary market histories.

Kill me now!

Thoughtful summary of the installation- hope MoMA listens!